Is almost everyone wrong about America’s AI power problem?

Published

This post is part of our Gradient Updates newsletter, which shares more opinionated or informal takes about big questions in AI progress. These posts solely represent the views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Epoch AI as a whole.

In AI circles, there’s a common argument that goes: “The US is horrible at building power, but China’s great at it. And since power is so important for the AI race, China wins by default.”

This line of reasoning is everywhere. NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang used it to argue that “China is going to win the AI race” last month. It features in Situational Awareness, a series of essays about how the world’s in a fierce race to AGI, which received a seal of endorsement from Ivanka Trump. There’s even an entire Dwarkesh podcast episode called “China is killing the US on energy. Does that mean they’ll win AGI?”.

But we think this argument is overstated — power bottlenecks likely won’t dramatically or permanently impede the data center buildout in the US. Claims about America’s AI power predicament are partially based on a misunderstanding, and there are multiple promising approaches to meet America’s AI’s power demands. That means that people are overrating the strength of the power bottleneck, and how much that impacts the “race to AGI”.

So why do we believe this, and how could everyone be wrong about America’s AI power problem?

America’s AI power predicament — or not?

You don’t have to look hard to find horror stories of US power infrastructure. There are transmission lines that need approval from 1,700 landowners, electric truck charging depots that need to wait up to a decade to connect to the grid, and weather events that plunge millions of Texans into rolling blackouts.

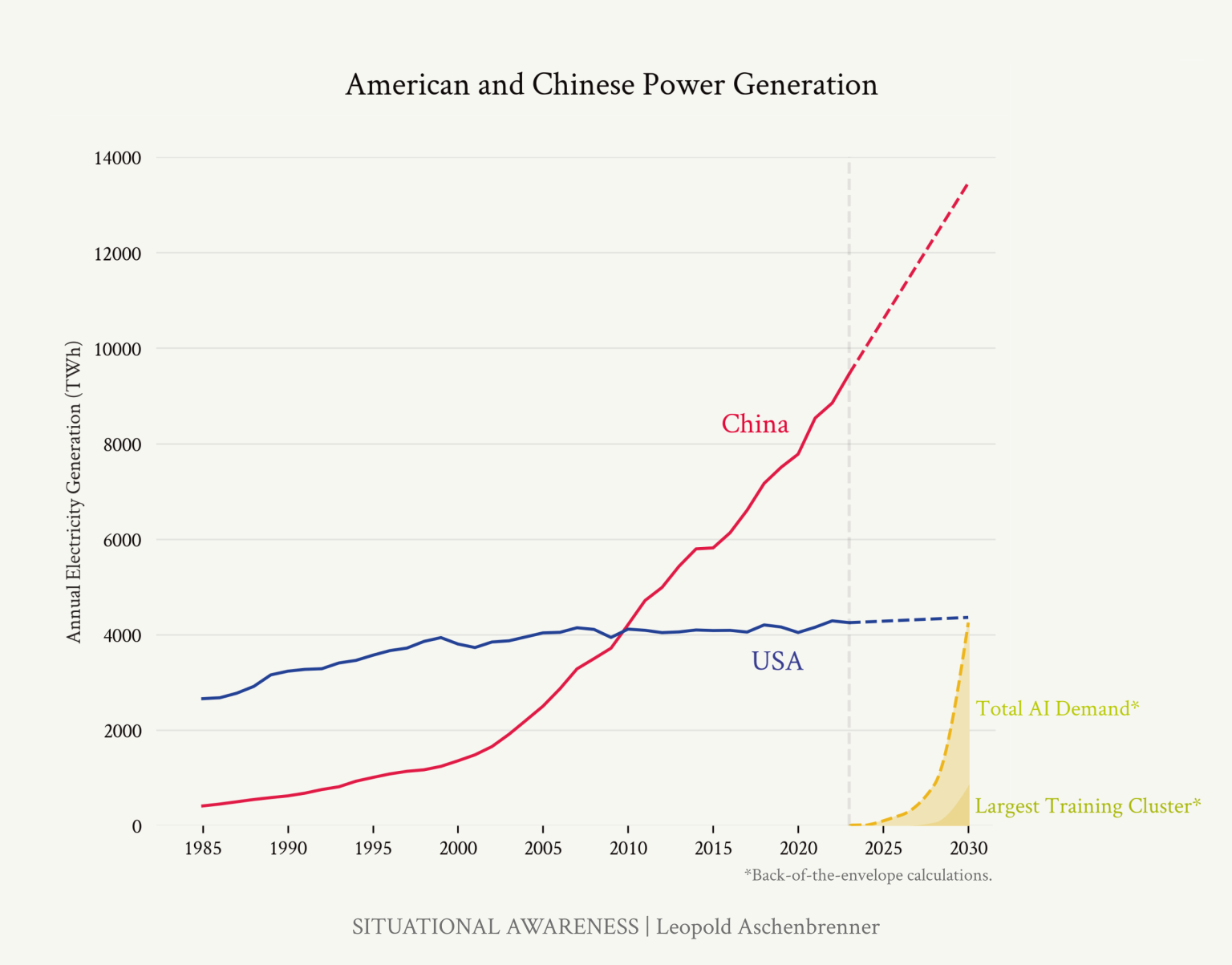

And we can also just look at the numbers — over the last four decades, total US power supply has been flat as a board, whereas China’s has far surpassed it:

Source: Situational Awareness

So there’s a natural story here — regulations have killed the US’ ability to build power and “win the AI race”. And there’s some truth to this; legal hurdles can impede power buildout.

But this story points the finger at the wrong thing. It assumes that US power capacity has stagnated because America can’t build -– without first checking whether demand actually warranted more capacity! Maybe Americans just haven’t wanted much more power!

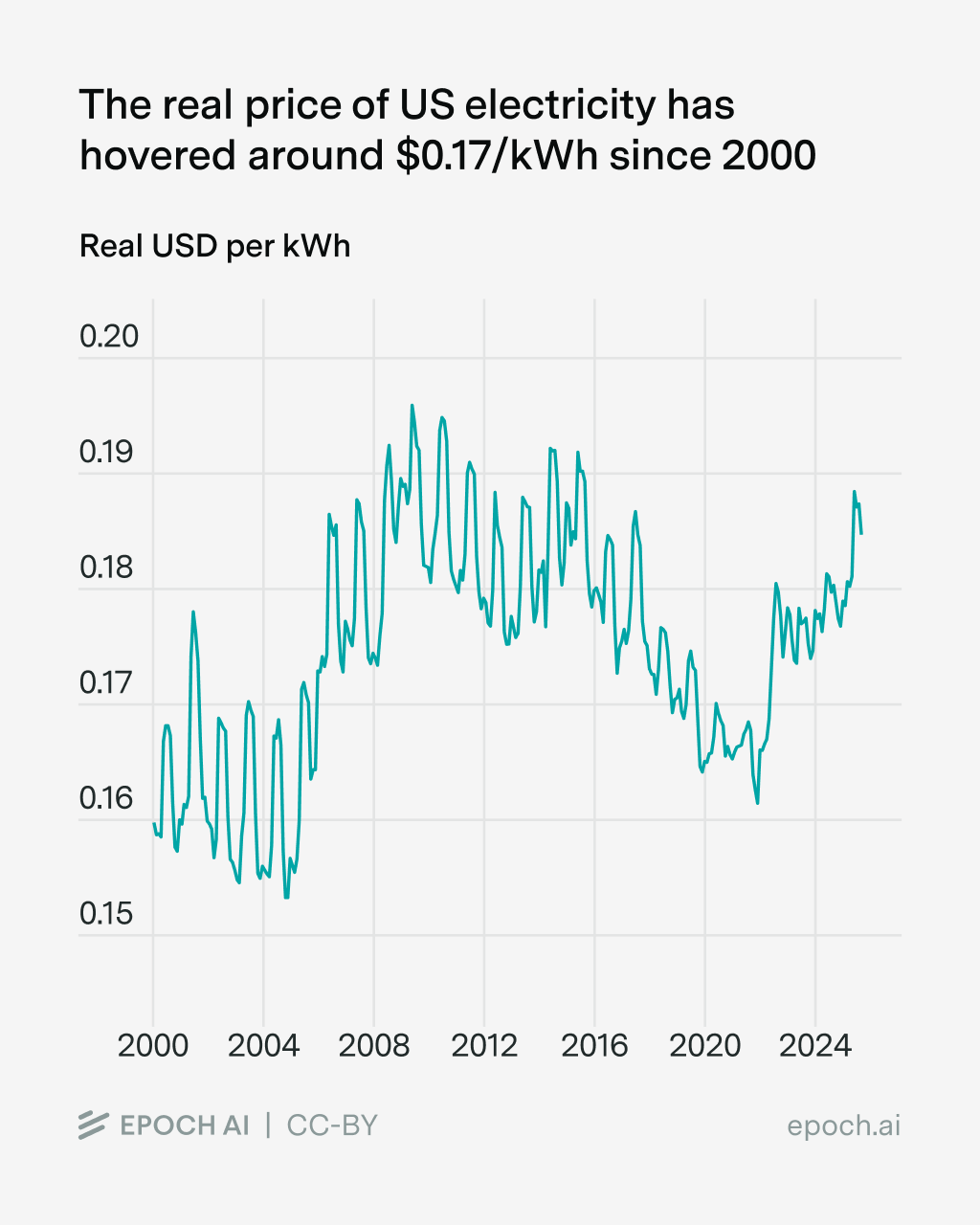

Indeed, we see that real energy prices have been basically stagnant over the last twenty years.1

Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, dividing average electricity prices by the Consumer Price Index (with January 2025 = 100).

Moreover, as we’ll see, there’s actually excess capacity available on the grid. So this suggests that the problem wasn’t an inability to expand supply; rather it was that demand remained stagnant for most of the last few decades.

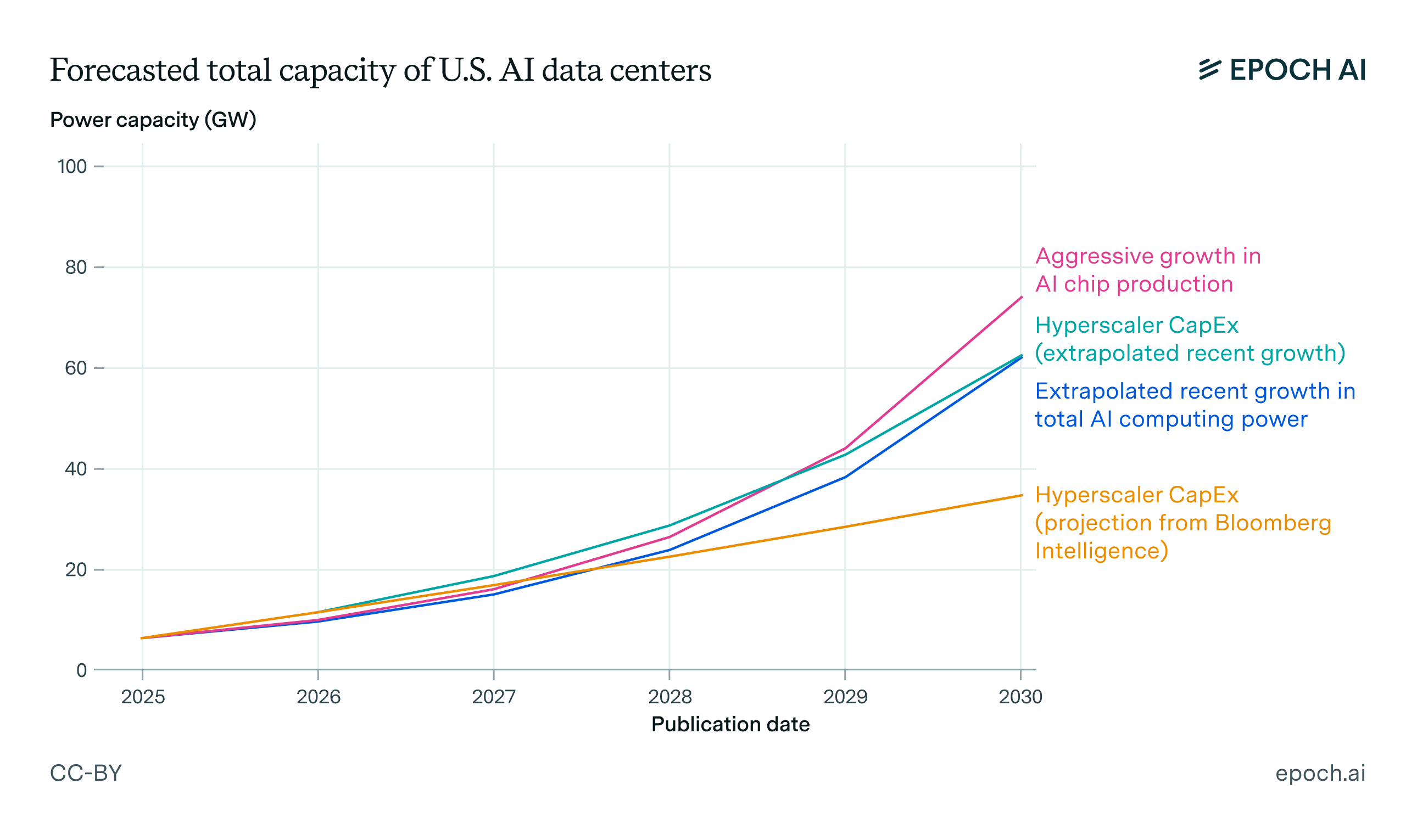

You might be thinking, “there’s a big elephant in the room here — isn’t AI going to hugely increase US power demand?” And you’d be right. AI has driven recent spikes in power demand, and AI data centers in the US will need 30 to 80 GW of power by 2030.

Let’s assume that AI’s power demand grows aggressively, reaching 100 GW by 2030.2 That means the US would need to build out four times more power than California needs on average. We haven’t seen this much relative growth in electricity demand since the 1980s.3

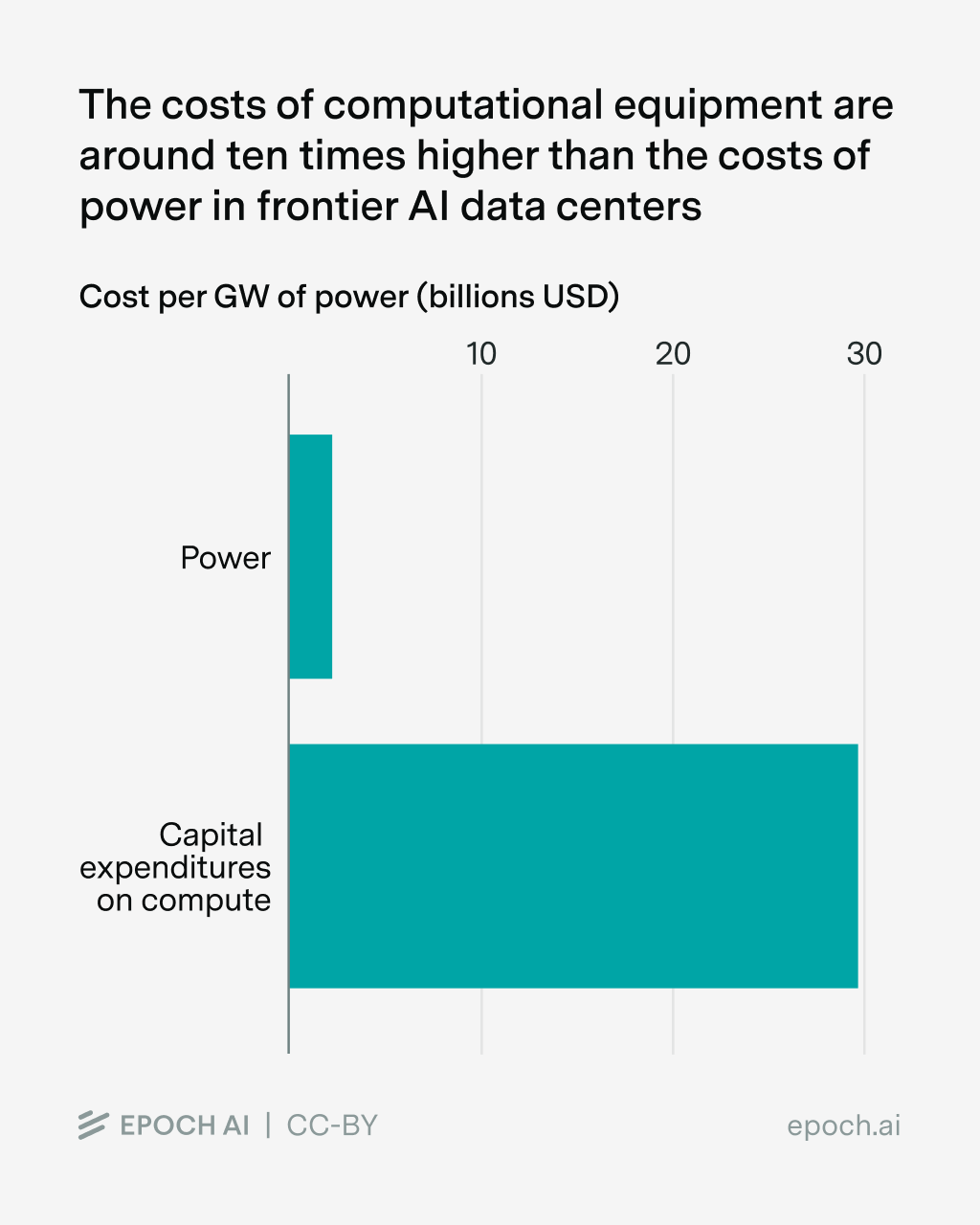

But we think the US can likely meet this demand anyway. As long as there’s enough will to invest in AI scaling, there’ll be enough will to pay for the power. After all, power is a relatively small slice of the cost of running a data center — chips are far more expensive. If companies are willing to shell out for massive AI chip clusters, they won’t balk at paying a premium for electricity.

Plucking fruit from the power tree

This sudden spike in power demand after decades of stagnation means that the US is off to a standing start. But the flip side is that America hasn’t really tried to meet this kind of demand surge, so there’s still a bunch of relatively low-hanging fruit to be picked.

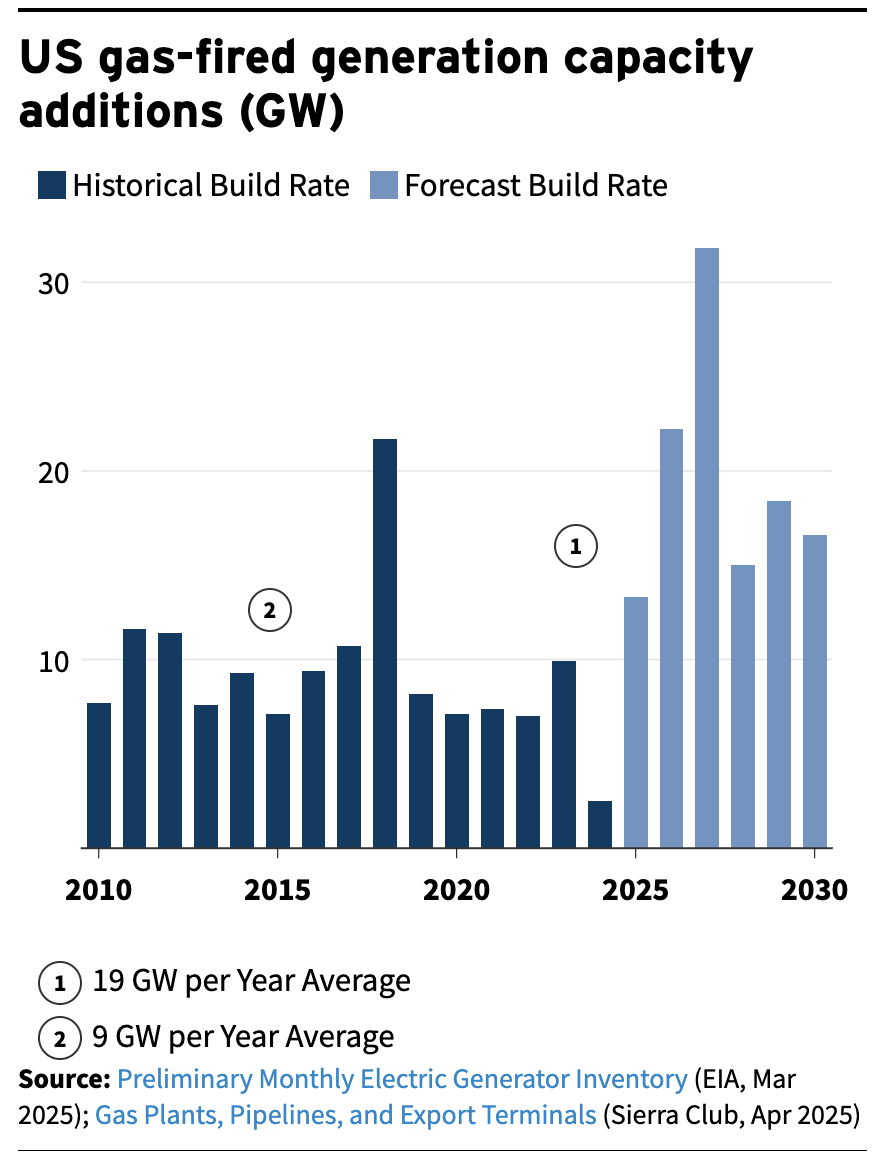

Natural gas: Digging power out of the ground

Probably the most salient way to supply power is to build out natural gas — it’s relatively cheap and can be built fast (e.g. without immediately connecting to the electrical grid), which is why it powers frontier data centers like OpenAI’s Stargate Abilene and Meta’s Hyperion.

So how much natural gas could we build out? As a starting point, natural gas providers already aim to grow their production a lot. Consider the three largest gas turbine manufacturers, which collectively make up something like 85% of market share:

- GE Vernova says they’ll build 20 GW per year by 2026 and 24 GW per year by 2028.

- Mitsubishi Heavy plans to double their gas turbine production over two years, though sadly we don’t know what this means in terms of absolute power capacity

- Siemens plans to boost their gas turbine production capacity from 17 GW per year in 2024, to 22 GW per year between 2025 and 2027, and over 30 GW a year by 2028.

So it’s hard to say overall, but even if we just sum up the power contributions from GE Vernova and Siemens until 2030, that brings us beyond 200 GW. Accounting for Mitsubishi Heavy and other producers should bring us well beyond that. This power isn’t necessarily produced for US consumers (last year US consumption contributed 20% to 40% of the revenues of each company),4 but it does strongly suggest that these companies would be able to supply the AI power demand for several years to come.

This is also broadly consistent with older forecasts for natural gas production in the US, with over 100 GW produced by 2030.

Now we can’t quite declare victory yet, because of two issues. First, natural gas capacity doesn’t translate directly into data center capacity. So if there’s 100 GW of added natural gas capacity, grid planners might only expect around 80 GW of that to be reliably available during peak demand.5

The second (and trickier) issue is that not all of this power capacity goes to AI — but we don’t know how much. GE Vernova states that their backlog goes into 2028, and “only a small portion of those orders relate to data centers and AI”. But what’s a “small portion”? 3%? 30%? At the very least, AI probably makes up a pretty substantial portion of the most recent orders — 65% in the case of Siemens. And if people are willing to spend big on AI scaling, many of these orders could potentially be bought from other use cases.

Even after we account for these two issues, it seems like natural gas could cover a big chunk of expected AI power demand. And planned natural gas buildouts are actually quite modest: companies are planning to spend several billions on equipment for natural gas through 2028, which sounds like a lot but pales in comparison to the trillions needed for IT equipment. If companies are going to spend a lot on buying GPUs anyway, they’re going to be willing to pay a fraction of that amount for power. So there’s plenty of room to increase turbine production even more if they really wanted to.

This can mean taking steps that aren’t the most cost-effective by traditional power industry metrics, because the time-to-power is what matters most for AI. For example, rather than using standard “combined-cycle” gas turbines, AI companies are turning to smaller “simple-cycle aeroderivative gas turbines”. Although these jet engine-based turbines can cost more than their combined cycle counterparts, they’re also much faster to build.6

But there’s perhaps an even better example of how gas turbines could be rapidly scaled up — Elon Musk’s xAI. Founded in 2023, xAI needed to catch up quickly with the likes of Anthropic and OpenAI. That meant building data centers fast and powering them in pretty out-of-the-box ways — renting gas before connecting to the electrical grid, deploying natural gas turbines prior to receiving permits, and even importing and disassembling a gas plant from overseas!

Solar: Raining power down from the sky

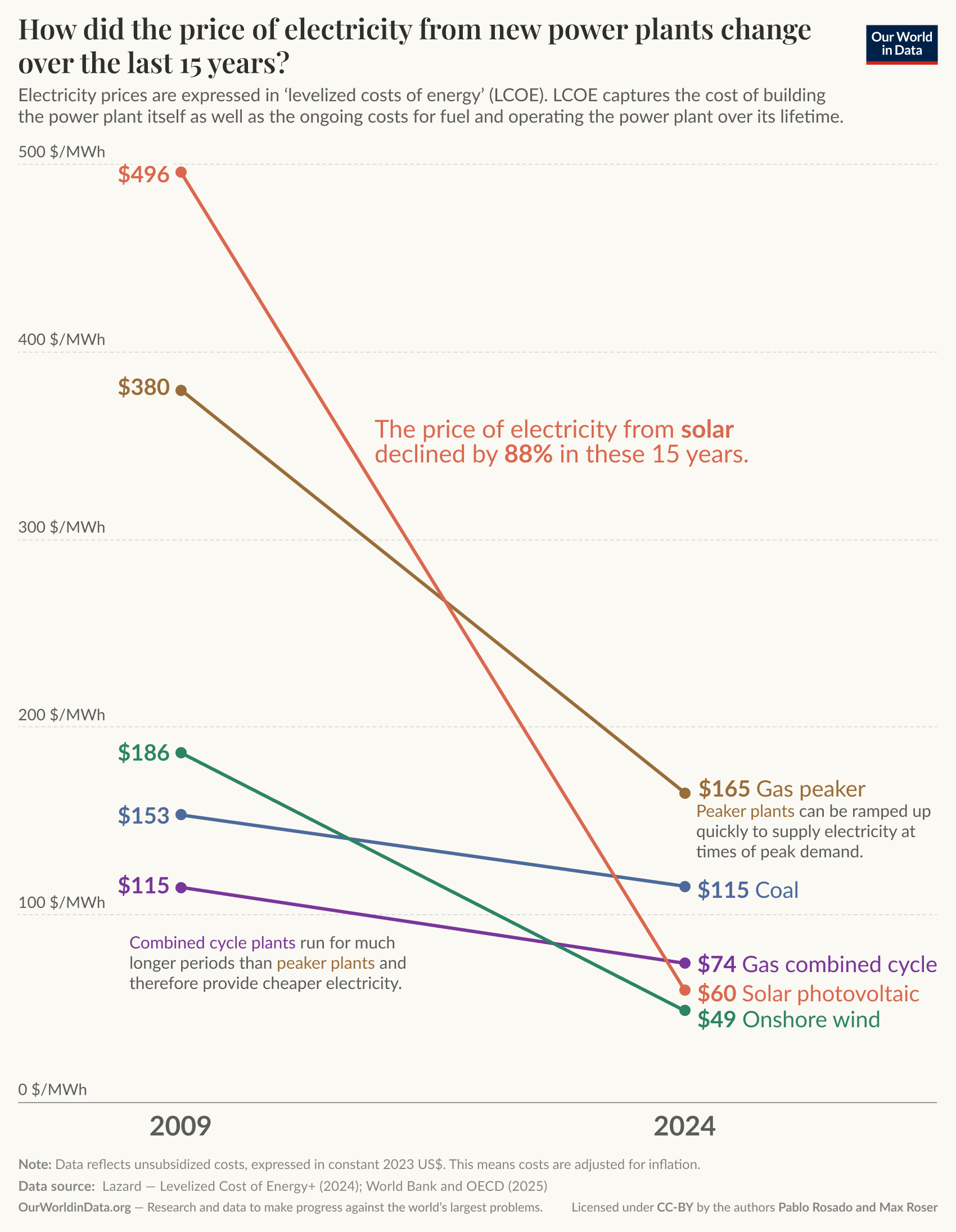

While there’s still room for Elon Musk-esque “just get the power ASAP” approaches, we should also consider other sources of power. And the best candidate for this is solar energy — it’s more environmentally friendly, and the price has famously been dropping monstrously fast compared to other energy sources:

More importantly, solar power can be scaled a lot. Solar installations have grown roughly exponentially for at least the last decade, and even if US policy headwinds stopped us from going beyond 2024’s rate of 40 GW per year, we’d end up with 200 GW over the next five years.

Once again, we shouldn’t jump the gun and declare victory just yet — not all of this solar capacity translates into data center capacity. In practice, we might have to cut this by a factor of five to 40 GW over the next five years. This is a huge drop, but it still covers a good chunk of AI’s power demand, and like with natural gas, there’s a lot of room to grow the supply of solar power.

Importantly, the core bottlenecks are things like installation costs, permitting costs, and connecting solar power to the grid. It’s less about manufacturing — the US can basically manufacture or import as many solar panels and batteries as they could realistically want. For instance, US solar manufacturing capacity reached 55 GW in the second quarter of 2025 alone, which is more than enough to supply installations for the full year. So if only you could bypass these bottlenecks, you could unlock a lot of power.

This is exactly what was proposed in a report late last year — rather than waiting to connect renewables to the grid, simply move off-grid. The idea is to have many “microgrids” that are powered by solar and a bit of natural gas backup. Each microgrid would individually power data centers, such as from 100 MW to 1 GW in size. According to them, this could unlock over 1000 GW of potential power for data centers in the US Southwest alone. And they think this could be built out fast:

“Estimated time to operation for a large off-grid solar microgrid could be around 2 years (1-2 years for site acquisition and permitting plus 1-2 years for site buildout), though there’s no obvious reason why this couldn’t be done faster by very motivated and competent builders.”

That said, this approach is still pretty speculative, and has a bunch of hiccups. For one, you need a lot of land — 2 GW of solar power needs as much space as all of Manhattan!7 Moreover, while you might want your data center to run 24/7, you can’t generate solar power at night. If you’re connected to the grid this isn’t too big of a deal because you can draw on spare grid capacity from other power sources, but going off-grid makes this more challenging. These reasons are probably why (to our knowledge) there haven’t yet been plans for gigawatt-scale data centers to be mainly solar-powered.

But as with natural gas, these obstacles don’t seem insurmountable. For one, a lot of US land gets a ton of sun — enough land for over ten thousand Manhattan-sized solar arrays.8 Moreover, batteries can help substantially support off-grid approaches. There was a roughly 20 GW increase in battery capacity from 2024 to 2025, and if this is sustained this would bring us to 100 GW by 2030.9 And in many ways this is too conservative — batteries could be imported, and also repurposed from Electric Vehicles, which currently make up the vast majority of battery demand. In fact there’s already some precedent for this — companies like Redwood Materials and Crusoe were exploring this approach earlier this year.

Demand response: Acquiring power “out of thin air”

So far we’ve looked at two ways of building power — but there’s one more wildcard that could make a huge difference. This is what Dean Ball cheekily describes as pulling “gigawatts out of thin air”, the more technical term for which is “demand response” (yet another name is “data center flexibility”).

As crazy as it might sound, the US electricity grid is oversupplied most of the time. That’s because power infrastructure is built to handle peak demand, like when everyone’s turned up their air conditioning during a heatwave.10 But most of the time, there’s actually abundant spare power in the grid, enough to run (say) a 1 GW data center.11

To make this work, data centers would need to reduce power use during peak demand. This can be tricky — for one, data centers would need to credibly commit to decreasing their power draw when necessary. This probably also involves deliberately curtailing AI workloads, which raises technical challenges — but not insurmountable ones. Even today, large training runs have to contend with spontaneous AI chip failures that force the entire process to stop, but data center operators have been able to manage these quite successfully.

If demand response actually works, it could unlock a lot of power: One study finds that if data centers could cut power demand by just 0.25% across the year, they could get around 76 GW of spare capacity.12 That’s 75% of the power of the entire US nuclear power plant fleet, and gets us a lot of the way to meeting AI’s power demand. If you’re willing to curtail power demand even more, you could get substantially more power — e.g. a 1.0% power cut across the year gives you 126 GW of power.

This almost sounds too good to be true, but is already gaining traction. Google has agreed to implement this in Indiana and Tennessee. The Electric Power Research Institute launched a project last year to demonstrate demand response in real markets. And Emerald AI has been working with companies like Oracle and Nvidia to implement it in practice.

This doesn’t mean it’ll all be smooth sailing. The estimates in the aforementioned study might be too optimistic.13 And moreover, a demand response proposal by the PJM (the largest grid operator in the US) has been met with some strong pushback from big tech and data centers. But the pushback seems mostly about the specific proposal,14 and given that multiple actors have their own proposals, this doesn’t seem like a big strike against demand response in general.

Adding up the numbers

Now let’s put together all the numbers. Our best projections suggest that the US will need around 100 GW of power by 2030. And if we look at individual power sources, we see there’s a lot of potential to meet this demand. Demand response unlocks tens of gigawatts of power, and plausibly over 100 GW. Solar and natural gas individually contribute many tens more gigawatts under existing projections, and there’s likely substantial room to grow by going off-grid or just scaling up equipment spending.

These different approaches can complement each other to some extent. For example, traditional buildouts of solar power could require five to seven years to connect to the grid, which is too slow. But if data centers procure their own solar power generation capacity and combine this with demand response, they could cut this wait time down to two years.

And let’s not forget that there are other power sources too. For example, next-generation geothermal power seems close to medium-scale commercial deployment — one pilot project is already online and there are several startups backed by AI “hyperscalers” that promise hundreds of megawatts by 2028. By 2035, these buildouts could plausibly add 40 GW of geothermal power.

So if we combine all these approaches, it looks quite likely that the US will have enough power for AI scaling until 2030.

Strictly speaking this isn’t quite enough because we don’t just care about the total power — to train AI systems, this power often needs to be concentrated in a single location. And if current trends persist, this might mean truly massive training runs with 4 to 16 GW by 2030. However, this is a big if, because a lot of model development is now less focused on performing a single large training run in one location.

But we doubt even this will be that much of a blocker. Frontier AI companies seem to be doing a pretty good job at quickly finding locations for gigawatt-scale data centers. Consider how OpenAI and Oracle were able to do this for multiple sites within roughly a year, as part of their Stargate project. And even if we can’t find individual locations that fit the bill, companies could split training across multiple locations to circumvent local power constraints.

So is everyone wrong about this?

Taking a step back, what we’re saying is perhaps rather outrageous. Are we really saying that everyone is wrong? Do we really think that we know better than all the frontier AI companies, all the AI policy researchers, and all the utility companies CEOs? If these approaches are so good, why isn’t everybody implementing them?

The thing is, they are implementing them! As we saw earlier, new frontier AI data centers often use natural gas, and companies like Google are now implementing demand response.

And to the extent that these approaches aren’t being put into practice, remember that a lot of this is very new. The US has seen “stagnant power demand for a few decades followed by a huge AI-shaped spike, roughly since ChatGPT was released three years ago”. And three years is ancient history by AI standards, but a blink of an eye for the power industry. So we shouldn’t be surprised that many people have been thinking about power through an outdated lens, tailored to a world without several gigawatt-scale megaprojects spun up each year.

The pressures of AI competition have transformed the picture. Consider electrical transformers and transmission lines: connecting a new facility to the grid traditionally requires building these out, a process which can take years. But in an industry where multi-year waits are a death sentence, companies are increasingly turning to off-grid generation and demand response programs which sidestep connecting new power to the grid.15

Why then are so many actors complaining about the size of the power bottleneck? We think the obvious reason is true — there are indeed challenges to accessing power for AI scaling! Overcoming these challenges often means using out-of-the-box techniques for acquiring power, and might end up costing more. So there are incentives to try and reduce the price of power as much as possible.

The upshot: we doubt that these challenges alone are strong enough to impede AI scaling. Power bottlenecks will likely add months — but not years — to build-out times. Even if power prices tripled, they would still be substantially lower than the costs for AI compute — in current frontier data centers, the cost of AI chips is roughly ten times higher than that of power! If people are willing to build out huge data centers with loads of chips, then they’re also willing to pay a premium to build out power.

The question that matters the most, then, is whether people will be willing to spend on AI scaling. So far, spending on building power has been fairly conservative, perhaps due to uncertainty in future power demand.16 But if there continues to be intense economic and geopolitical incentives to build AI infrastructure in the US, then the AI industry will probably be able to secure a large share of new power generation, especially for smaller-scale AI data centers used for inference or decentralized training.

This finally brings us back to the original argument — does China’s power advantage mean that they “win by default” (whatever that means)? Not necessarily. It’s still the case that China can build power faster than the US, but America’s power bottleneck is much weaker than many people make it out to be. Moreover, the whole reason electrical power matters for AI is that it’s used to run AI chips. But as things currently stand, China still has to overcome serious deficits in the quantity and quality of their AI chips to gain a compute advantage over the US — and that would be true even with unlimited power capacity.

The upshot is this: power does pose a real challenge, but it matters a lot how big this challenge is. At the very least, we doubt that power bottlenecks will be strong enough to substantially slow down US AI scaling. For that, we’re not holding our breath.

We’d like to thank Lynette Bye and Yann Riviere for their feedback and support on this post.

Notes

-

The same is true for retail sales of electricity. ↩

-

This isn’t a strict upper bound, for example some estimates are substantially higher, in the ballpark of 250 GW (and if building data centers costs $30 billion per GW, this amounts to $7.5 trillion!). We’re more skeptical that we’ll reach these scales, but it’s possible. ↩

-

100 GW would be around 10% of America’s peak power capacity. If we spread this out over four to five years, this works out to a growth rate of 2% to 3%, which we haven’t seen since roughly the 1980s. ↩

-

For example, US consumption contributed around 40% of revenue for GE Vernova, about 20% for Siemens, and roughly 20% for Mitsubishi Heavy. ↩

-

This is captured more formally by the Effective Load Carrying Capacity (ELCC), which is around 80% for natural gas. ↩

-

Good data is somewhat sparse, but there is some suggestive evidence. For example, a report from the Energy Information Administration shows a handful of examples where simple-cycle aeroderivative turbines cost over 50% more than their combined-cycle counterparts. Similarly, smaller simple-cycle gas turbines can take 18 to 24 months to go from order to operation, and larger combined-cycle gas turbines take 36 to 48 months. ↩

-

Each GW of solar power needs around 30 square kilometers of land, so for 2 GW you’d need around 60 square km, which is around the land area of Manhattan. ↩

-

There’s around 1.5 million square km of US land that receives over 5 kWh/m2/day. That’s roughly the equivalent of 5 hours a day of full midday sun — for comparison, Los Angeles has an average of 5.3 kWh/m2/day. Given that Manhattan’s land area is around 60 square km, this is enough for 25,000 Manhattans. ↩

-

This is consistent with projections from the US Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory, which expects US battery cell capacity to grow by around 930 GWh through 2030. If batteries are 10-hour-systems, this would be enough to support around 90 GW of power. ↩

-

A better example comes from the UK. During commercial breaks, many TV-watchers simultaneously take the opportunity to boil water to prepare another cup of tea or coffee. That leads to a predictable power spike of around 200 to 400 MW. ↩

-

This doesn’t necessarily preclude training runs that need much more than 1 GW of power. For example, it’s likely possible to train AI models across multiple data centers in decentralized fashion, even if each data center needs less than a gigawatt. ↩

-

In practice, this doesn’t quite mean cutting power 0.25% of the time (i.e. 22 hours per year) — these power reductions are usually partial rather than fully cutting out the data center’s power load. Instead, the authors estimate this would be spread out over 85 hours. But that’s still just under 1% of the total hours in a year. ↩

-

In general, we worry it’s hard to know what happens when you apply something as novel as demand response at close to 100 GW scales (whereas building out this much power is something with much more historical precedent). ↩

-

PJM proposed that data centers could avoid capacity charges by accepting priority curtailment during emergencies. But if not enough people volunteer, PJM would mandate participation. Data centers objected that this singled them out for inferior service while existing customers faced no equivalent obligation, and utilities argued PJM lacked authority to create what amounts to a new class of retail service. ↩

-

In the longer run, more substantial buildouts should be possible — for example, there’s historical precedent for much larger supply of transformers and investment into transmission lines. ↩

-

This in turn depends on the economic returns to further compute scaling — if these are high enough, this would help justify substantial investments. ↩