How close is AI to taking my job?

Published

This post is part of Epoch AI’s Gradient Updates newsletter, which shares more opinionated or informal takes on big questions in AI progress. These posts solely represent the views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Epoch AI as a whole.

I. Searching under the streetlight

How can we anticipate when AI will be able to do our jobs? AI researchers have mainly tried to answer this question by building complex AI benchmarks. The problem is that this approach is fundamentally flawed.

A good example of this is OpenAI’s GDPval. On paper, it’s a cool benchmark that captures AI performance on a wide range of real-world job tasks in the US economy. The benchmark tasks were meticulously constructed to be realistic, involving the hard work of hundreds of experts and likely millions of dollars — placing it among the most expensive economics papers of all time.1 If there’s one benchmark that could be the leading indicator of AI job automation, it’s GDPval.

Unfortunately, the benchmark seems to have fallen prey to the same issue plaguing most other benchmarks. Shortly after release, AI models have beaten the human baseline — GPT-5.2 reached parity with industry experts, and Claude Opus 4.6 likely does even better. And yet, the actual economic impacts of AI remain muted. The benchmark doesn’t fully reflect the economic effects, and so it’s falling short in its role as a leading indicator for automation.

This isn’t really OpenAI’s fault, rather it’s a fundamental challenge with AI benchmarks. These need to be designed so that you can automatically run evaluations quickly and regularly, but this constrains us to tasks that are “clean” and close-ended. So when we try to generalize these to the messy workflows and fuzzy tasks of the real world, we inevitably encounter many issues.

If this is right, then the problem is that we’ve mostly been searching under the streetlight, primarily tracking progress on the things that benchmarks can easily measure. But it also suggests that there’s a way to search beyond the streetlight: we just need to sacrifice a bit of rigor and ease of evaluation, and in exchange we can get a better sense of automation on truly real-world tasks.

Here’s the idea: pick out a set of actual work tasks that people do on a regular basis, and then see how well AI is able to do them, and regularly check how much better AI is getting. This kind of subjective AI evaluation on realistic tasks isn’t a totally novel idea — for example, in AI safety, models are often “red-teamed” in a way that involves subjectively rating their risk levels. There are also many studies looking at AI uplift on real-world tasks. But I think there’s room for a lot more of this kind of analysis, especially because all the benchmarks seem to be running into the same bottlenecks. So I think it’s an underrated way of tracking AI’s potential impacts in actual jobs.

So to demonstrate how this could work, I decided to try getting today’s best AI agents to do my job.

II. Trying to automate my job away (for science)

The first step is to pick out three tasks that people have actually done at Epoch, with a heavy bias towards my own work. I thought it’d be good to focus on things that capture the full gamut of important AI bottlenecks — long-horizon planning and execution, creativity and taste, and so on. So these are tasks that should be relatively difficult for AIs today, but play an important role in my work.

After that, I spent 30-60min trying to get AIs to autonomously solve each task and analyzed where current models seem to be falling short. I could’ve done a lot more to improve AI performance on each task, but I wanted this to broadly reflect how I’ve been using AI in practice given my time and work constraints. Then I roughly forecasted when I thought AIs would do them to my liking (i.e. such that I’d personally use their outputs in practice), and how well AIs would do by the end of the year.

So if we put things together, this should give a more concrete picture of how close AI is to taking my job. Here’s where I ended up:

| Task | Current | Forecasts: When will AI succeed on its first try? |

|---|---|---|

| Replicate an interactive web interface for a complex economic model | Claude Code creates a functional interface, but it's full of factual inaccuracies and missing components, making it unusable. | 10% by the end of 2026, and 50% by late 2027. |

| Analyzing provided data and writing a publication-worthy article about the results | Claude Opus 4.5's post looks ok on the surface, but is "off" in many ways — style, factual accuracy, etc. There are enough issues that I'd rather rewrite the post from scratch. | 5% by the end of 2026, and 50% by around late 2028 or early 2029. Note that the "first try" includes Epoch staff giving two rounds of comments/feedback. |

| Porting an article from Google Docs to Substack and Epoch's website | ChatGPT Atlas successfully ports some of the article to Substack, but it stumbles badly on the footnotes. | 10% that it can do the whole thing by the end of 2026 really slowly. 50% by mid-2028. |

My probabilities that an AI successfully completes the given task by the specified date. For a task to be "completed", the final product needs to be good enough for me to want to use it in practice. Tasks are done autonomously by the AI except for the second task, where two rounds of comments are provided.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean that I expect to lose my job by early 2029 — more on that later. But first, let’s dive into the details of the tasks.

Task 1: Replicating an interactive web interface for an economic model

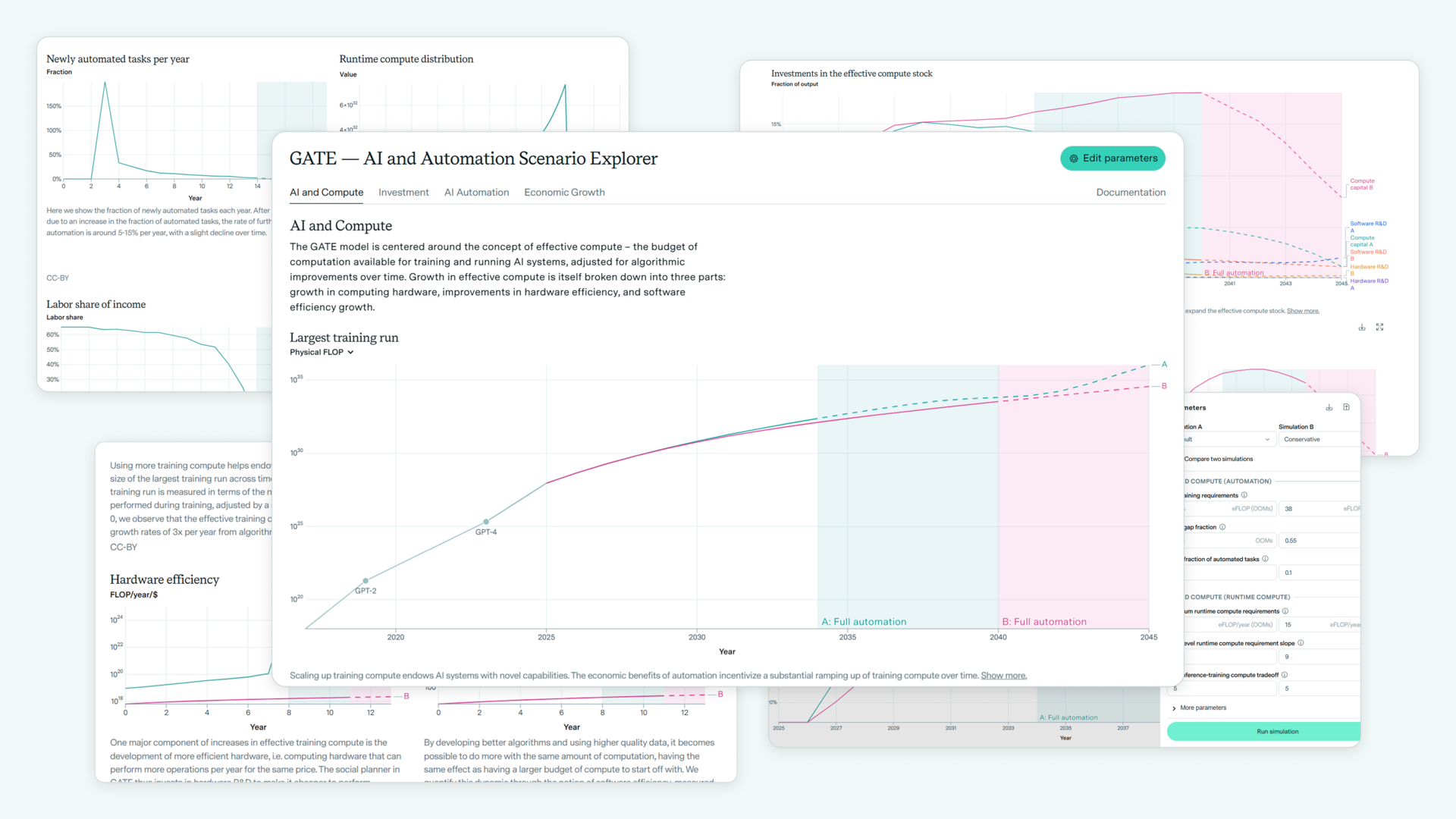

About a year ago, we at Epoch released a complex economic model of AI automation, which we called the GATE model. And by “complex”, I mean that it has over forty parameters, is solved by some clunky variant of gradient descent, and has a bunch of add-ons that can make the simulation especially unstable.

To accompany the release, we provided an interactive web interface that lets users input their own parameters, look at a bunch of fancy graphs about how economic growth could go crazy, and read some documentation. The point is, it’s by no means a simple thing to implement, and the frontend isn’t a piece of cake either.

Here’s what that looks like:

So the first task is this: Can an AI model build a functional replica that’s as good as the published web playground?2 The AI is given access to the academic paper and the original webpage, which includes a bunch of documentation. It’s also provided with descriptions on which graphs need to be created, as well as parameter ranges for each of the parameters.3

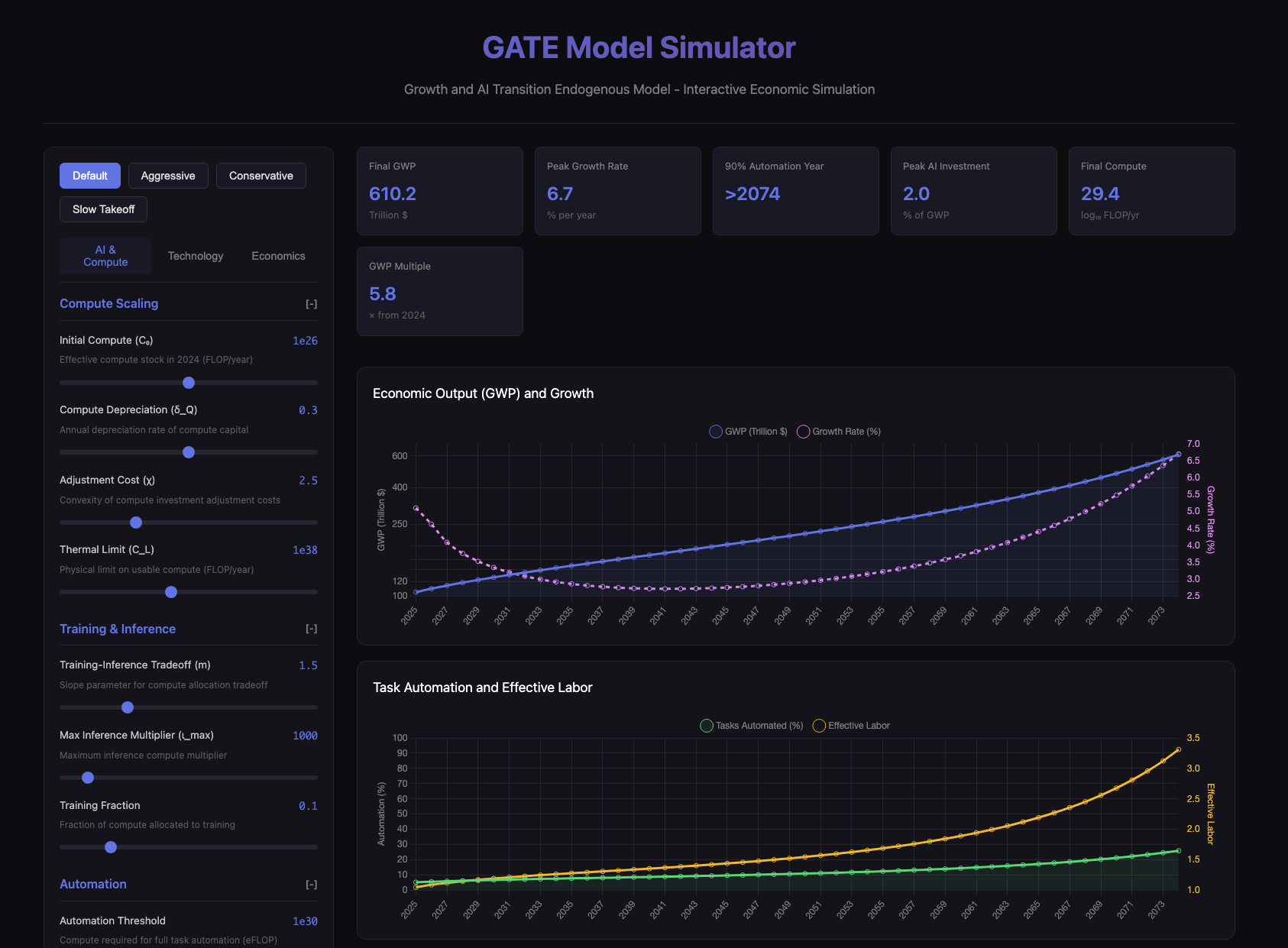

I asked Claude Code to implement this, mainly because it’s widely regarded as the best tool for coding. Initially it complained about the message being too long if I dumped in the whole paper PDF, so I gave it the arXiv URL. It then spent a while looking up the equations in the paper, quickly wrote some HTML and Javascript, and this was the result:

This looks pretty cool to start off with, and it’s certainly a functioning website, but it goes downhill from there. The most crucial issue is that many of the model predictions differ vastly from the official simulation, which suggests something went wrong in the reimplementation. For example, the GWP change is way lower than what you observe in the mainline scenario in our actual GATE model.4 Another issue is that the website has missing features, like a “comparison mode” that allows users to compare different parameter settings.

The big question is: how well will AI systems do on this task in the future? I think we can think about this in several ways.

One is to consider the trend in METR’s time horizons, which I think applies reasonably well given that this is a software task that’s pretty well-defined. By the end of the year, we expect AI to be able to do tasks roughly one day long with a 50% success rate.5 In comparison, I’d guess that this task would take several days for a person familiar with the paper and is able to play around with the web interface. So this task seems plausibly solvable by December, but it’s less likely than not.

Still, it’s a clunky task with a lot of moving parts. Perhaps the hardest part is the backend, which involves some nitty-gritty optimization with numerical stability problems — you’d probably need to stare at many graphs and iterate to get it right. The frontend has its own challenges, but I think Claude Code’s implementation isn’t so bad on this front.

Putting things together, I think that models have about a 10% chance of implementing this as well as the existing live version by the end of the year. In my mind, this’ll probably be because models flunk some part of the code implementation for the economic model’s dynamics, or there are some non-obvious bugs that need a bunch of people trying diverse things on the website to identify. Fixing these issues takes a bit more time, and by late 2027 or early 2028, I think there’s a roughly even chance that this task gets solved.

So my guess is that our web dev team will continue to produce interactive web interfaces that are of a similar complexity, like Epoch’s distributed training simulator and webpage for frontier data centers, at least in terms of core functionality. And if you work on things of a similar difficulty, I think you’ll probably be in the same boat.

Task 2: Writing an article

Now let’s move on to the second task: Can AI write articles for this newsletter?

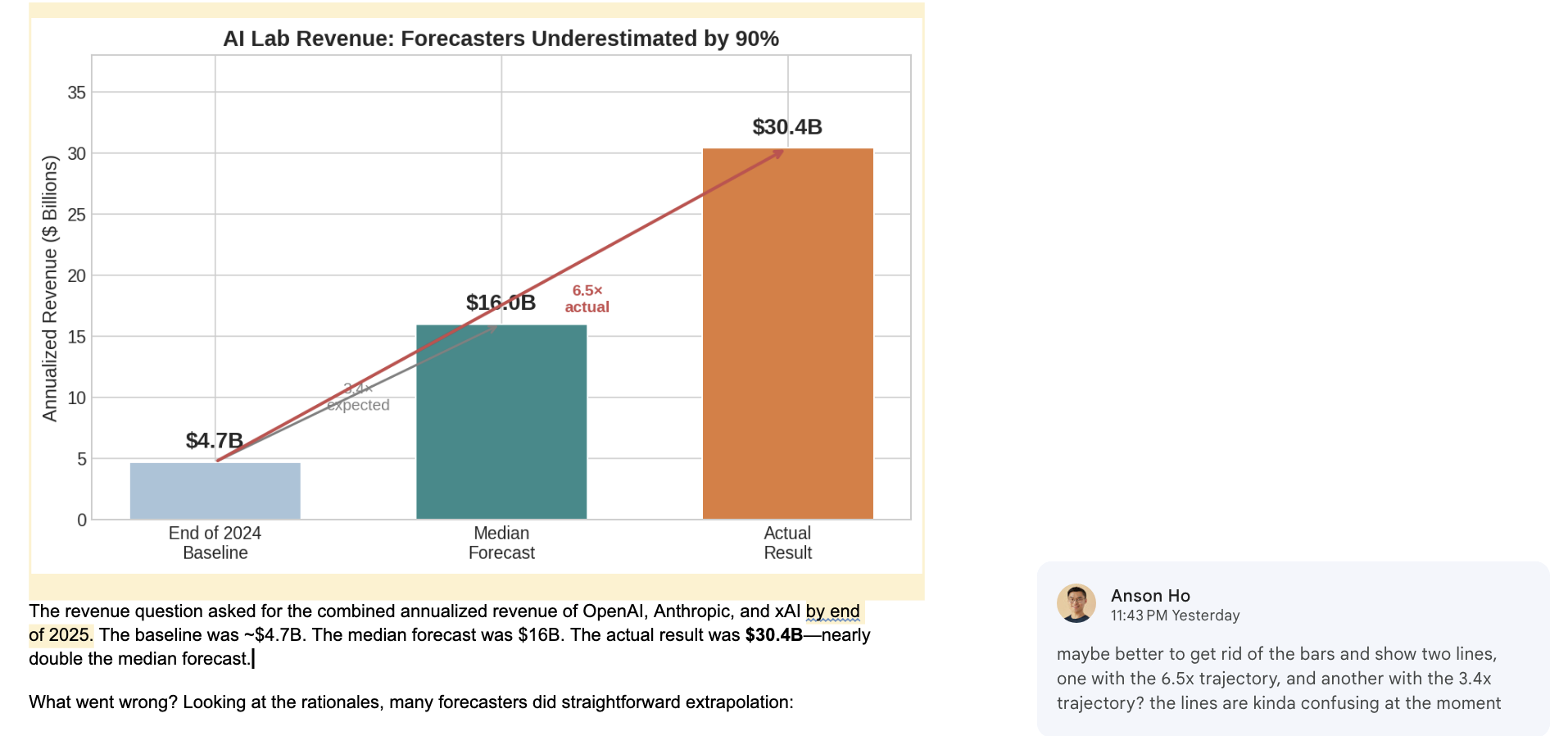

To test this, I asked Claude Opus 4.5 to try and write one of my previous articles, which summarized how well people forecast AI progress in 2025 (notably, this means that Claude didn’t need to come up with the post idea itself). I gave it the list of questions and resolutions from the AI Digest (who ran the survey), all the results, and asked it to look at our previous posts to get a sense of our style.6

Its initial attempt at this wasn’t very good — it didn’t include graphs, links to relevant sources, and even left out some of the questions from the survey entirely! The writing style was a tad stiff, the structure was odd (e.g. the survey demographics were put near the end of the article), and the results weren’t very well justified. For example, here’s Claude explaining why forecasters significantly underestimated progress on the cybersecurity benchmark Cybench:

Cybersecurity evaluations have received less public attention than coding or math benchmarks, and forecasters may have had weaker mental models of the rate of progress in this domain. It also suggests that capability improvements on agentic tasks may be occurring faster than the broader forecasting community appreciates.

As far as I can tell, there isn’t any justification for any of the claims in the paragraph — don’t ask me how Claude came to these conclusions!

That said, it’s a bit unfair of me to judge it purely on its zero-shot performance — when I’m writing I usually get lots of helpful comments from others. So I gave Claude two rounds of feedback, totalling around forty comments, each about one to two sentences long. For example:

Unfortunately, while this solved some problems (like adding graphs and links), new issues emerged. Sometimes Claude would fail to resolve subtle graphical issues that would normally involve multiple rounds of iteration, like putting text in the right part of the graph. And there were many such problems littered throughout the article — even after my feedback, the writing was still stilted, had many inaccuracies, and terms that weren’t explained to my liking.

In the end, the post wasn’t unreadable, but there were so many small errors that I felt better off going back to square one and rewriting the post from scratch. So, at least in the near future, I’ll continue to be writing articles.

But just how near is the “near future”? When will AI essentially be able to write a full article of this complexity that I’ll really like, after giving a few rounds of comments? Unlike Task 1, I don’t see a clear trend that we can extrapolate to forecast progress. So I think we’ll probably need to turn to the age-old tradition of “vibes-based forecasting”.

On the one hand, there are a bunch of reasons to expect AI to get a lot better on this task very soon. One is that AI writing has improved a ton over the last few years, and it’s not crazy at all to expect that this continues. Labs have also been making efforts to improve writing, as we’ve seen with models like GPT-4.5, and people are increasingly building writing benchmarks.

What’s more, the task of writing an article isn’t just about the quality of the writing itself. In many ways, Claude was actually more bottlenecked on things like data analysis and graphing, as well as insufficient context about my writing preferences. But I expect AIs to get vastly better at practically any kind of coding-related task over the next few years, and they’ll also have a greater degree of continual learning, which would help surmount these barriers. Surely it’s not that hard to give AIs context about my writing preferences and Epoch’s worldview?

On the other hand, there are also reasons for slower progress, at least relative to domains like coding. For one, labs are probably going to focus on things that are more lucrative than writing, like finance and coding. Consider that there are around 1.7 million software engineering jobs in the US, with a median pay of $133,000. That’s several times higher than both the total writing jobs (around 350,000) and median pay (in the ballpark of $70,000).7

This relative focus on coding becomes even stronger because writing is one of those fuzzy tasks where it’s hard to say what’s good or bad. So it’s hard to measure improvements in writing, making it hard for AI companies to “hill-climb” their way to becoming Ernest Hemingway. This is also part of the reason why reasoning seems to help more on tasks like math than writing.

Personally, I find the arguments for slower progress more compelling. I’d probably give a 5% chance that AI will be better at writing these posts than me by the end of the year, and maybe a 50% around late 2028/early 2029. For posts that are more complex and require coming up with novel ideas, I’d probably go a bit later than that, but that depends on how well I can actually write those posts!

This means that I’m more bearish on AI progress for this task compared to the previous one — that’s interesting because I actually find this task a lot easier. Perhaps this is a case of “Moravec’s Paradox strikes again” — AI is often good at the things humans find hard, and bad at the things we find easy.

Task 3: Publishing an article

The third and final task may be even more susceptible to Moravec’s Paradox: Can AI port an article from Google Docs to Substack and Epoch’s website? This requires agentic computer use, which seems to trip up AI models in strange ways.

Most of this task is boring grunt work, spent going through many tedious steps, across different platforms. We start off with a finalized draft of the post and thread written up in Google Docs, which then gets ported to two places:

- Epoch’s website: This involves making a new branch on the GitHub repo for Epoch’s website, creating a new markdown document with the right metadata, copying all the content in, formatting the tables, attaching images, and so on.

- Substack: This one is easier, but there are some oddities of Substack. You can’t make tables, so we have to take screenshots of the tables from our website’s preview. And footnotes don’t get copied over from Google Docs, so you need to add them manually.8

Overall, it usually takes me about two hours to do this task. If only it were as simple as a single copy and paste, life would be so much easier — or so I thought. To my surprise, Claude with its Chrome browser extension struggles to copy+paste from Google Docs to Substack:

- First it tried to download the file. It clicks on

File, but then complains that no window opened, even though I could see it opening. Not sure what’s going on there. - Then it tried to highlight everything in the Google Doc and do a copy+paste operation. But for some reason it wasn’t able to do this for all the text, and had to resort to copying text block by block, scrolling down the page.

- This was taking forever, so I tried restarting the task, (naively?) hoping that things would be better this time. Unfortunately it got worse: it ran into the same issue, but instead of copying text block by block, it opted for the strategy of scrolling down the page and reading the text screenshot by screenshot!

After it started doing that, I threw in the towel and decided I’d try another agent. This time it was ChatGPT Atlas’ turn. Initially it seemed to get stuck identifying which tabs were open, but after another try it managed to get going. To my surprise, it successfully copied the main post onto Substack — after watching Claude’s agonizing failed attempts to copy and paste text, this was mindblowing.

Alas, I only managed to feel the AGI for about fifteen more seconds before ChatGPT started making some really silly mistakes. It was transferring the footnotes, but it didn’t use Substack’s footnote feature, and it didn’t add all the footnotes. Even worse, the footnotes were all made up, and there was a bizarre formatting issue where ChatGPT placed the cursor in the wrong place:

ChatGPT Agent successfully ports the main text of our last Gradient Update, but messes up the footnotes.

So at the moment, AI agents seem to fail quite miserably at this task, and are also extremely slow. This corroborates pretty well with Claude’s performance on Pokémon, as well as the finding that METR’s time horizons are 40-100× shorter for visual computer use tasks compared to their headline numbers. For example, this could bring a five hour (300 minute) time horizon down to a three minute time horizon.

But while the time horizons are much shorter, the growth rate is about the same as the METR’s main results, with roughly two doublings each year. Today’s agents are also much better at Pokémon compared to a year ago. If these trends hold, we should expect to see very fast progress in the near future.

And people are trying to make it happen — labs have been creating agents like ChatGPT Agent, Kimi K2.5’s Agent Swarm, and Claude Cowork, and we’re still in the early days of AI agents. There are also huge incentives for labs to push in this direction, overcoming bottlenecks to AI adoption among billions of computer users worldwide.

Of course, there are some bottlenecks that we need to account for. One bottleneck that I learned the hard way is reliability. When ChatGPT Agent was messing around on Substack, there was a point when the cursor hovered over the button to publish the post. I was practically freaking out at the idea of sending an already-published post with garbled footnotes to over ten thousand subscribers, but fortunately nothing happened, and I was able to intervene.

By the end of the year, I’d probably give roughly a 10% chance of AIs completing the task autonomously, though they might need to do it very very slowly. In the median case, I think AI agents will get much further in the task — porting most of the footnotes correctly, adding content to an IDE and attaching the images, and so on. But I think it’ll be very slow, there’ll be missed steps, and more likely it’ll get stuck on something that’s trivial to most computer-literate humans.

Looking further out, I think there’s a 50-50 chance that AI agents can complete this task by around mid-2028.

III. What this all means for my job, and perhaps yours too

Let’s take stock of what we’ve seen so far. Based on the three tasks, today’s AI seems unable to fully generate complex interactive web simulations, is okay at writing articles, and very bad at publishing them. But I also think that we’re only a few years away from AIs that can solve these tasks, and the tasks that are hard for me might not be the ones that are hard for the AIs. It depends on how amenable those tasks are to things like RL, and on how economically valuable they are.

Looking at the forecasts, the last task that I expect to fall comes in early 2029, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that AI will replace me by 2029. The obvious reason is that these three tasks don’t comprehensively represent my job, and I wasn’t trying to pick out the hardest-to-automate tasks. So even if AI is able to solve them, there’s a good chance that I’ll just work on other things instead. The bottleneck shifts to something new.

For example, we at Epoch have mostly prepared for podcast episodes by brainstorming questions in advance. Now let’s say that Claude becomes better than us at coming up with good podcast questions in advance. Then the bottleneck shifts from writing questions to being able to understand them and ask good follow-ups during the recording itself, in a way that understands what kinds of things humans might be curious about on the fly.

The bottleneck is shifting from us Epochians preparing good questions in advance, to being able to understand them and ask good follow ups during real conversation. But there may still be some time before Humanity’s Last Podcast. (Source: Epoch After Hours)

So if we want to know when AI takes my job, rather than just “do a bunch of tasks”, we also need to know how far these bottlenecks can shift. My “strong opinion, loosely held” is that this can go surprisingly far. One reason is that Moravec’s Paradox really messes with our intuitions. AI capabilities are very spiky, and if we don’t know what this spikiness looks like, then it becomes hard to predict what kinds of things will stump future AIs. This becomes doubly hard because it’s often hard to know what bottlenecks exist until you actually encounter them. The last bottlenecks will eventually fall. But if we forecast job automation by saying “job X is just doing Y” and predicting when AI can do Y, we’ll likely produce overly aggressive timelines.

In practice, I imagine the path towards automating my job probably looks something like this: in the next year or two, my day-to-day work will look pretty similar to today at a high level. But if we narrow down to subtasks, we’ll see a lot more AI use, like how GPT-5.2 is now essentially my default search engine instead of Google. Between 2027 and 2029, AI will continue to get much better at coding, writing, and agentic computer use, until eventually it’s able to do large chunks of what I do today. I’ll increasingly shift my attention to things that are hard to stuff into AI contexts, manage multiple AIs, deal with bizarre AI weaknesses, and do more high-level ideation or other fuzzy tasks. This continues for a handful more years before it’s finally game over for my job.

What about you and your job?

For the most part, I’ve framed this post around AI progress on my job, and how I personally expect to be using AIs. But what about everyone else and their jobs?

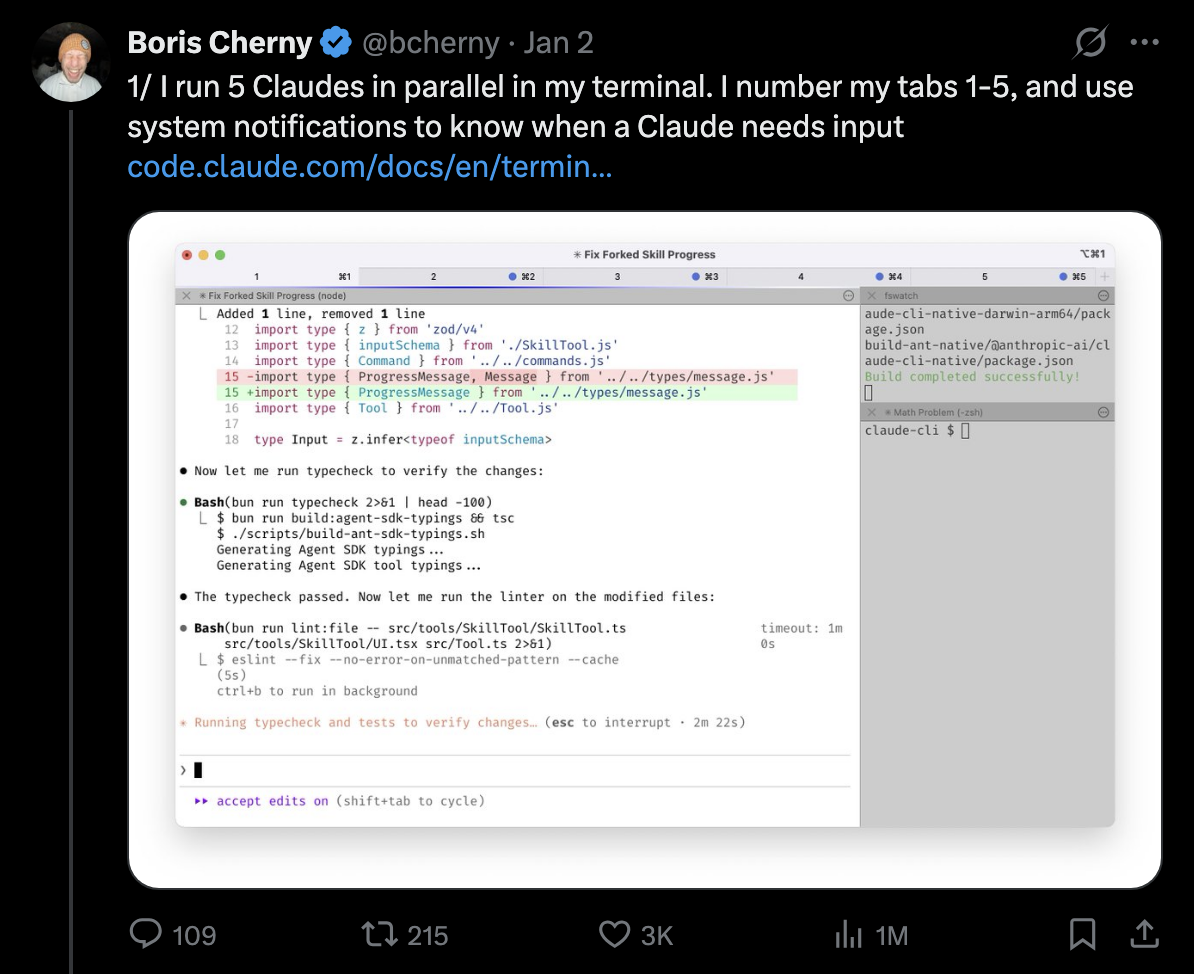

First of all, while I probably use AI more than 99% of people on Earth, there are some people who use AI much more than me. I suspect this is especially true for coders based in the Bay Area. As a particularly extreme example, Boris Cherny (the creator of Claude Code) puts my puny Claude + Chrome extension setup to shame:

This can strongly influence just what kinds of tasks AI systems can or cannot do. Some AI users might be able to elicit AI capabilities a lot better than I can — this in turn impacts how AI changes their work, and how far AI is from taking their jobs.

There’s clearly also a ton of variation across different occupations, which you can see from resources like How People Use ChatGPT and the Anthropic Economic Index, or even just by asking your friends. So unless you and I work on similar things, I can’t say much about AI timelines on your specific job.

The solution is to have lots of people from various AI-exposed fields do a similar analysis to what I’ve done — that means economists, lawyers, mathematicians, and so on. The procedure is simple: pick out three work tasks that you do regularly (and ideally spend a large fraction of your time on), and then spend a bit of time getting AI to attempt the task. Document how much progress the AI makes, look at the bottlenecks, and make your forecasts for when they’ll be overcome.9

I’m hoping that this’ll give a lot more concrete evidence about how AI can be used and is bottlenecked in truly real-world tasks, especially in your own personal situation. So it might be worthwhile trying to get AI to automate your job — you might learn things about both your life decisions and the future of labor automation. That’s something that even a million-dollar benchmark may not be able to do.

I’d like to thank JS Denain, David Owen, Greg Burnham, Luke Emberson, Markov Grey, Jaime Sevilla, and Lynette Bye for helpful feedback and support.

Notes

-

I don’t know of an official source for how much this cost, but we can do a ballpark estimate: The full benchmark has 1320 tasks, each of which needs 7 hours of expert time to complete (on average). Assuming that experts are paid around $75 per hour, that adds up to around $700,000, just accounting for the costs of measuring human performance. But this ignores costs from building the benchmark, operations, and multiple rounds of expert review, which I think are likely to raise the costs into the millions. ↩

-

Hat tip to Jérémy and Tangui for the inspiration behind this question. ↩

-

So far, the code for both the model and the web implementation have been private or shared with a handful of collaborators, so I think the chances of test set leakage are quite low. Note also that this task isn’t 100% the same as the one that our web dev team had to deal with — it’s easier in some ways (e.g. there’s a completed paper and webpage which the AI can reference), but it’s harder in some other ways (e.g. it doesn’t have the benefit of iterating many times with the people who designed the economic model). ↩

-

Funnily enough, this trajectory probably seems more plausible to most economists, who are extremely skeptical about the plausibility of explosive economic growth. That said, even to them, the GWP growth rate should look quite odd — it starts off at around 5-6% without much automation, then goes down to 3% with more automation, and then goes back up to 5-6% around the time of full automation! ↩

-

To give a sense of where this number comes from, the current time horizon at a 50% success rate is around 6 hours — Claude Opus 4.5’s time horizon is 5.3 hours, and GPT-5.2 (high)’s time horizon is 6.6 hours. Each year we might see roughly two doublings of the time horizon, so by the end of the year this might be about a day long. ↩

-

I gave it links to several of our most recent Gradient Updates articles, and asked it to look at them to get a sense of the formatting and style. I also asked it not to look at any other Gradient Updates, so that it wouldn’t look at the already-published version of the target post — probably there’s a smarter way of doing this but I think it should do the trick for the sake of this post. ↩

-

Here’s a rough justification: according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are 135,400 “writers and authors” jobs, 56,400 “technical writer” jobs, 115,800 “editors”, and 49,300 “news analysts, reporters, and journalists”. In total that’s around 350,000 writers, and if we eyeball the numbers in these links the median pay is probably in the ballpark of $70,000. ↩

-

If you know of a better way to do this, please let me know. ↩

-

Our previous caveat applies here: this tells you about how much your job will be transformed, but it doesn’t totally nail down when it’ll be fully automated, because the bottleneck shifts from one task to another. ↩