This post was written in collaboration with Exponential View.

Update (March 6, 2026): We’ve revised our estimates based on new information and feedback from people familiar with the matter. In particular, we’ve 1) increased our estimate of inference costs given new information, and 2) lowered our estimate of sales and marketing spending after excluding inference compute costs associated with serving free users. This article reflects these updated figures.

Are AI models profitable? If you ask Sam Altman and Dario Amodei, the answer seems to be yes — it just doesn’t appear that way on the surface.

Here’s the idea: running each AI model generates enough revenue to cover its own R&D costs. But that surplus gets outweighed by the costs of developing the next big model. So, despite making money on each model, companies can lose money each year.

This is big if true. In fast-growing tech sectors, investors typically accept losses today in exchange for big profits down the line. So if AI models are already covering their own costs, that would paint a healthy financial outlook for AI companies.

But we can’t take Altman and Amodei at their word — you’d expect CEOs to paint a rosy picture of their company’s finances. And even if they’re right, we don’t know just how profitable models are.

To shed light on this, we looked into a notable case study: using public reporting on OpenAI’s finances,1 we made an educated guess on the profits from running GPT-5, and whether that was enough to recoup its R&D costs. Here’s what we found:

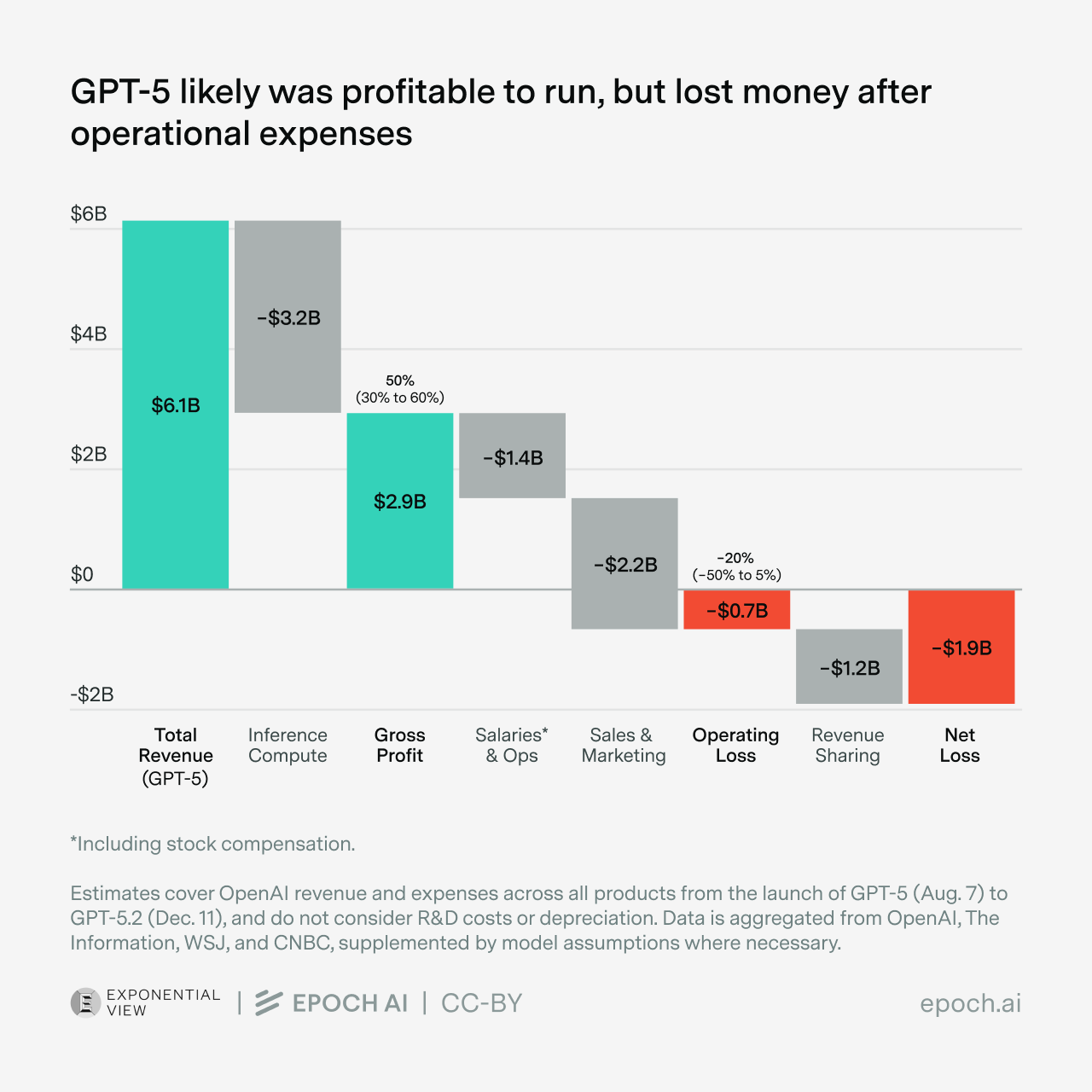

- Whether GPT-5 was profitable to run depends on which profit margin you’re talking about. If we subtract the cost of compute from revenue to calculate the gross margin (on an accounting basis),2 it seems to be about 30% — lower than the norm for software companies (where 60-80% is typical) but still higher than many industries.

- But if you also subtract other operating costs, including salaries and marketing, then OpenAI just barely broke even, even without including R&D. And they likely ended up at a loss after accounting for their revenue-sharing deal with Microsoft.

- Moreover, OpenAI likely failed to recoup the costs of developing GPT-5 during its 4-month lifetime. Even using gross profit, GPT-5’s tenure was too short to bring in enough revenue to offset OpenAI’s R&D costs in the four months prior to launch. So if GPT-5 is at all representative, then at least for now, developing and running AI models is loss-making.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that models like GPT-5 are a bad investment. Even an unprofitable model demonstrates progress, which attracts customers and helps labs raise money to train future models — and that next generation may earn far more. What’s more, the R&D that went into GPT-5 likely informs future models like GPT-6. So these labs might have a much better financial outlook than it might initially seem.

Let’s dig into the details.

Part I: How profitable is running AI models?

To answer this question, we consider a case study which we call the “GPT-5 bundle”.3 This includes all of OpenAI’s offerings available during GPT-5’s lifetime as the flagship model — GPT-5 and GPT-5.1, GPT-4o, ChatGPT, the API, and so on.4 We then estimate the revenue and costs of running the bundle.5

Revenue is relatively straightforward: since the bundle includes all of OpenAI’s models, this is just their total revenue over GPT-5’s lifetime, from August to December last year.6 This works out to $6 billion.7

At first glance, $6 billion sounds healthy until you juxtapose it with the costs of running the GPT-5 bundle. These costs come from four main sources:8

- Inference compute: $4 billion. This is based on public estimates of OpenAI’s total inference compute spend in 2025, and assuming that the allocation of compute during GPT-5’s tenure was proportional to the fraction of the year’s revenue raised in that period.9 This cost covers serving both paid and free users.10

- Staff compensation: $1 billion, which we can back out from OpenAI staff counts, reports on stock compensation, and things like H1B filings. One big uncertainty with this: how much of the stock compensation goes toward running models, rather than R&D? We assume 40%, matching the fraction of compute that goes to inference. Whether staffing follows the same split is uncertain, but it’s our best guess.11,12

- Sales and marketing (S&M): $0.5 billion. This would include expenses such as their SuperBowl ad and business sale campaigns, promotions and discounts, and other related expenses. Notably, it excludes the compute costs of serving free users.13,14

- Legal, office, and administrative costs: $0.2 billion, assuming this grew between 1.6× and 2× relative to their 2024 expenses. This accounts for office expansions, new office setups, and rising administrative costs with their growing workforce.

So what are the profits? One option is to look at gross profits. This only considers the direct cost of running a model, which in this case is just the inference compute cost of $4 billion. Since the revenue was $6 billion, this leads to a profit of around $2 billion, or gross profit margin of around 30%.15 This is lower than other software businesses (typically 70-80%) but high enough to eventually build a business on.

On the other hand, if we add up all four cost types, we get close to $6 billion. That’s close to the revenue, so on operating profit terms, we think the GPT-5 bundle just about broke even.16

Stress-testing the analysis with more aggressive or conservative assumptions doesn’t change the picture much:17

| Type of profit margin | Description | Median estimate (conservative, aggressive) |

|---|---|---|

| Gross | Revenue minus inference compute costs | 30% (90% CI: 25% to 45%) |

| Operating (exc. R&D) | Revenue minus all costs Excludes R&D costs and the revenue sharing deal with Microsoft. | -5% (90% CI: -30% to 10%) |

Confidence intervals are obtained from a Monte Carlo analysis. Margins are rounded to the nearest 5%.

And there’s one more hiccup: OpenAI signed a deal with Microsoft to hand over about 20% of their $6 billion revenue,18 making them end up at a loss.19 This doesn’t mean that the revenue deal is entirely harmful to OpenAI — for example, Microsoft also shares revenue back to OpenAI.20 And the deal probably shouldn’t significantly affect how we see model profitability — it seems more to do with OpenAI’s economic structure rather than something fundamental to AI models. But the fact that OpenAI and Microsoft have been renegotiating this deal suggests it’s a real drag on OpenAI’s path to profitability.

In short, running AI models is likely profitable in the sense of having decent gross margins. But OpenAI’s operating margin, which includes marketing and staffing, is likely close to zero. For a fast-growing company, though, operating margins can be misleading — S&M costs typically grow sublinearly with revenue, so gross margins are arguably a better proxy for long-run profitability.

So our numbers don’t necessarily contradict Altman and Amodei yet. But so far we’ve only seen half the story — we still need to account for R&D costs, which we’ll turn to now.

Part II: Are models profitable over their lifecycle?

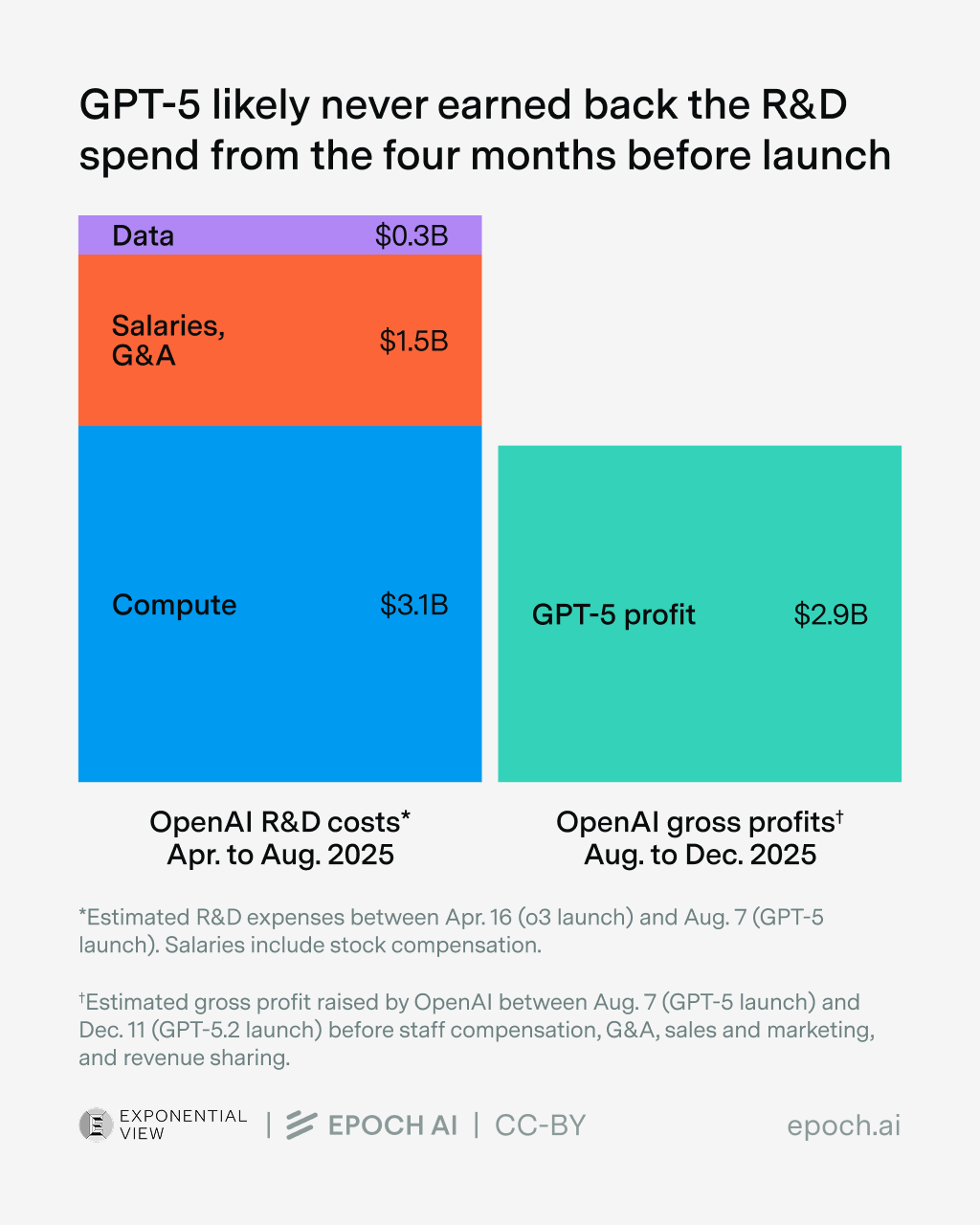

Let’s say we buy the argument that we should look at gross margins. On those terms, it was profitable to run the GPT-5 bundle. But was it profitable enough to recoup the costs of developing it?

In theory, yes — you just have to keep running them, and sooner or later you’ll earn enough revenue to recoup these costs. But in practice, models might have too short a lifetime to make enough revenue. For example, they could be outcompeted by products from rival labs, forcing them to be replaced.

So to figure out the answer, let’s go back to the GPT-5 bundle. We’ve already figured out its gross profits to be around $2 billion. So how do these compare to its R&D costs?

Estimating this turns out to be a finicky business. We estimate that OpenAI spent $15 billion on R&D in 2025,21 but there’s no conceptually clean way to attribute some fraction of this to the GPT-5 bundle. We’d need to make several arbitrary choices: should we count the R&D effort that went into earlier reasoning models, like o1 and o3? Or what if experiments failed, and didn’t directly change how GPT-5 was trained? Depending on how you answer these questions, the development cost could vary significantly.

But we can still do an illustrative calculation: let’s conservatively assume that OpenAI started R&D on GPT-5 after o3’s release last April. Then there’d still be four months between then and GPT-5’s release in August,22 during which OpenAI spent around $5 billion on R&D.23 But that’s still higher than the $2 billion of gross profits. In other words, OpenAI spent more on R&D in the four months preceding GPT-5, than it made in gross profits during GPT-5’s four-month tenure.24

So in practice, it seems like model tenures might indeed be too short to recoup R&D costs. Indeed, GPT-5’s short tenure was driven by external competition — Gemini 3 Pro had arguably surpassed the GPT-5 base model within three months.

One way to think about this is to treat frontier models like rapidly-depreciating infrastructure: their value must be extracted before competitors or successors render them obsolete. So to evaluate AI products, we need to look at both profit margins in inference as well as the time it takes for users to migrate to something better. In the case of the GPT-5 bundle, we find that it’s decidedly unprofitable over its full lifecycle, even from a gross margin perspective.

Part III: Will AI models become profitable?

So the finances of the GPT-5 bundle are less rosy than Altman and Amodei suggest. And while we don’t have as much direct evidence on other models from other labs, they’re plausibly in a similar boat — for instance, Anthropic has reported similar gross margins to OpenAI. So it’s worth thinking about what it means if the GPT-5 bundle is at all representative of other models.

The most crucial point is that these model lifecycle losses aren’t necessarily cause for alarm. AI models don’t need to be profitable today, as long as companies can convince investors that they will be in the future. That’s standard for fast-growing tech companies.

Early on, investors value growth over profit, believing that once a company has captured the market, they’ll eventually figure out how to make it profitable. The archetypal example of this is Uber — they accumulated a $32.5 billion deficit over 14 years of net losses, before their first profitable year in 2023. By that measure, OpenAI is thriving: revenues are tripling annually, and projections show continued growth. If that trajectory holds, profitability looks very likely.

And there are reasons to even be really bullish about AI’s long-run profitability — most notably, the sheer scale of value that AI could create. Many higher-ups at AI companies expect AI systems to outcompete humans across virtually all economically valuable tasks. If you truly believe that in your heart of hearts, that means potentially capturing trillions of dollars from labor automation. The resulting revenue growth could dwarf development costs even with thin margins and short model lifespans.

That’s a big leap, and some investors won’t buy the vision. Or they might doubt that massive revenue growth automatically means huge profits — what if R&D costs scale up like revenue? These investors might pay special attention to the profit margins of current AI, and want a more concrete picture of how AI companies could be profitable in the near term.

There’s an answer for these investors, too. Even if you doubt that AI will become good enough to spark the intelligence explosion or double human lifespans, there are still ways that AI companies could turn a profit. For example, OpenAI is now rolling out ads to some ChatGPT users, which could add between $2 to 15 billion in yearly revenue even without any user growth.25 They’re moving beyond individual consumers and increasingly leaning on enterprise adoption. Algorithmic innovations mean that running models could get many times cheaper each year, and possibly much faster. And there’s still a lot of room to grow their user base and usage intensity — for example, ChatGPT has close to a billion users, compared to around six billion internet users. Combined, these could add many tens of billions of revenue.

It won’t necessarily be easy for AI companies to do this, especially because individual labs will need to come face-to-face with AI’s “depreciating infrastructure” problem. In practice, the “state-of-the-art” is often challenged within months of a model’s release, and it’s hard to make a profit from the latest GPT if Claude and Gemini keep drawing users away.

But this inter-lab competition doesn’t stop all AI models from being profitable. Profits are often high in oligopolies because consumers have limited alternatives to switch to. One lab could also pull ahead because they have some kind of algorithmic “secret sauce”, or they have more compute.26 Or they develop continual learning techniques that make it harder for consumers to switch between model providers.

These competitive barriers can also be circumvented. Companies could form their own niches, and we’ve already seen that to some degree: Anthropic is pursuing something akin to a “code is all you need” mission, Google DeepMind wants to “solve intelligence” and use that to solve everything from cancer to climate change, and Meta strives to make AI friends too cheap to meter. This lets individual companies gain revenue for longer.

So will AI models (and hence AI companies) become profitable? We think it’s very possible. While our analysis of the GPT-5 bundle is more conservative than Altman and Amodei hint at, what matters more is the trend: Compute margins are falling, enterprise deals are stickier, and models can stay relevant longer than the GPT-5 cycle suggests.

We’d like to thank JS Denain, Josh You, David Owen, Yafah Edelman, Ricardo Pimentel, Marija Gavrilov, Caroline Falkman Olsson, Lynette Bye, Jay Tate, Dwarkesh Patel, Juan García, Charles Dillon, Brendan Halstead, Isabel Johnson, Markov Gray and Stefania Guerra for their feedback and support on this post. Special thanks to Azeem Azhar for initiating this collaboration and vital input, and Benjamin Todd for in-depth feedback and discussion.

Epoch AI has commercial relationships with multiple AI companies, including OpenAI and Anthropic. We disclose these relationships and associated conflicts of interest on our funding page. The views and analysis presented here are independent and not reviewed or endorsed by these companies.

Notes

-

Our main sources of information include claims by OpenAI and their staff, and reporting by The Information, CNBC and the Wall Street Journal. We’ve linked our primary sources though the document.

-

Technically, gross margins should also account for staff costs that were essential to delivering the product, such as customer service. But these are likely a small fraction of salaries, which are in turn dominated by compute costs — so it won’t affect our analysis much, as we’ll see.

Similarly, OpenAI’s revenue sharing agreement with Microsoft should, in theory, be counted as cost of goods sold and included in the gross margin per usual GAAP accounting. But the revenue sharing reflects more how the profits of the operation are divided between OpenAI and Microsoft, rather than an actual cost, so we have excluded it from the analysis.

-

We focus on OpenAI models because we have the most financial data available on them.

-

Should we include Sora 2 in this bundle? You could argue that we shouldn’t, because it runs on its own platform and is heavily subsidized to kickstart a new social network, making its economics quite different. However, we find that it’s likely a rounding error for revenues, since people don’t use it much. In particular, the Sora app had close to 9 million downloads by December, compared to around 900 million weekly active users of ChatGPT.

Now, while it likely didn’t make much revenue, it might have been costly to serve — apparently making TikTok-esque AI short-form videos using Sora 2 cost OpenAI several hundred million dollars. Here’s a rough estimate: In November (when app downloads peaked), Sora 2 had “almost seven million generations happening a day”. Assuming generations were proportional to weekly active users over time, this would mean 330 million videos in total. The API cost is $0.1/s, so if the average video was 10s long, and assuming the API compute profit margin was 20%, this adds up to 330 million × $0.1 × 10 / 1.2 ≈ $250 million. This is significant, but it’s minor compared to OpenAI’s overall inference compute spend.

-

Ideally we’d have only looked at a single model, but we only have data on costs and revenues at the company-level, not at the release-level, so we do the next best thing.

-

For the purposes of this post, we assume that GPT-5’s lifetime started when GPT-5 was released (Aug 7th) and ended when GPT-5.2 was released (Dec 11th). That might seem a bit odd — after all, isn’t GPT-5.2 based on GPT-5? We thought so too, but GPT-5.2 has a new knowledge cutoff, and is apparently “built on a new architecture”, so it might have a different base model from the other models under the GPT-5 moniker.

-

In July, OpenAI had its first month with over $1 billion in revenue, and it closed the year with an annualized revenue of over $20 billion ($1.7 billion per month). If this grew exponentially, the average revenue over the four months of GPT-5’s tenure would’ve been close to $1.5 billion, giving a total of $6 billion during the period.

-

One category of loss we are ignoring is the remeasurement of convertible interest rights, which purportedly amounted to half of OpenAI’s net loss in the first half of 2025. As with the revenue sharing deal, this only affects how profits would be divided between investors, not the product margins, so it is not relevant to the overall profitability of AI.

Another category of expense we didn’t account for is the cost of acquisitions. We also consider these not overly relevant to determine the overall profitability of operating OpenAI’s bundle of products, though it could be relevant to their R&D.

-

Last year, OpenAI earned about $13.1 billion in full year revenue, compared to $6.1 billion for the GPT-5 bundle. At the same time, it was reported they achieved a 33% gross margin on inference compute, implying they spent around $8.8 billion running all models last year, so if we assume revenue and inference compute are proportional throughout the year, they spent 6.1 billion / 13.1 billion × 8.8 billion ≈ $4.1 billion.

This is then increased by an additional $200 million from other sources of IT spending, including e.g. servers and networking equipment. The total is then still around $4.1 billion + $0.2 billion = $4.3 billion.

-

The Information reported that OpenAI spent around $4.5bn in serving paid users in 2025 of over $8bn spent in inference, implying they spent around $4bn serving free users. That’s it, they spent 40% to 50% of their compute serving free users.

-

H1B filings suggest an average base salary of $310,000 in 2025, ranging from $150,000 to $685,000. This seems broadly consistent with data from levels.fyi, which reports salaries ranging from $144,275 to $1,274,139 as we’re writing this. Overall, let’s go with an average of $310,000 plus around 40% in benefits. We also know that OpenAI’s staff counts surged from 3,000 in mid-2025 to 4,000 by the end of 2025. We smoothly interpolate between these to get an average staff count of 3,500 employees during GPT-5’s lifetime.

Then the base salary comes to: 3,500 employees × $310,000 base salary × 1.4 benefits × 40% share of employees working on serving GPT-5 × 127 / 365 period serving ≈ $0.2 billion (the 127 comes from the number of days in GPT-5’s lifetime).

We then need to account for stock compensation. In 2025, OpenAI awarded $6 billion to employees in stock compensation. Assuming they awarded them proportionally to staff count over the year, and given the exponential increase of staff counts, that would indicate that over 42% of the stock was awarded during GPT-5’s lifetime. Assuming 40% goes to operations as before, that results in $6 billion x 42% x 40% = $1 billion stock expense for operating the GPT-5 bundle. The total staff compensation would then be around $1.2 billion.

-

It’s debatable whether the very high compensation packages for technical staff will continue as the industry matures.

-

This is the line item we are most uncertain about. The Information reported that OpenAI had spent $2bn in sales and marketing during the first half of 2025, “nearly doubling what it spent in all of 2024.” However, they previously reported only $300mn in S&M spending during 2024. Our explanation of the discrepancy is that the 2025 H1 S&M spending includes the cost of inference for free users, OpenAI’s primary way of advertising their products, while the 2024 figure does not.

To estimate the S&M spending excluding compute, we assume it grew proportionally to revenue compared to their 2024 expenses. This would result in an estimate of $300mn 2024 S&M budget x $6.1bn GPT-5 tenure revenue / $4bn 2024 revenue = $500mn.

It’s possible this could have grown much more given OpenAI’s growing focus on B2B, which could be especially S&M expensive and include hefty commissions for closed deals.

-

This corresponds to around 10% of revenue during the period, which isn’t unusual compared to other large software companies. For example, Adobe, Intuit, Salesforce and ServiceNow all spent around 27% to 35% of their 2024-2025 revenue in S&M. That said, there are certainly examples with lower spends — for example, Microsoft and Oracle spend 9 to 15% of their revenue on marketing, though note that these are relatively mature firms — younger firms may spend higher fractions on S&M.

-

In comparison, Anthropic projected in mid-December a gross margin around 40%, suggesting gross margins in the 30-40% range might be representative of the industry.

-

How does this compare to previous years? The Information reported that in 2024 OpenAI made $4 billion in revenue, and spent $2.4 billion in inference compute and hosting, $700 million in employee salaries, $600 million in G&A, and $300 million in S&M. This implies a gross margin of 40% and an operating margin of 0% (excluding stock compensation).

-

In broad strokes, we perform a sensitivity analysis by considering a range of possible values for each cost component, then sampling from each to consider a range of plausible scenarios (a Monte Carlo analysis). The largest uncertainties that feed into this analysis are how much staff compensation goes to inference instead of R&D, S&M spending in the second half of 2025, and revenue during GPT-5’s tenure.

-

Two more caveats to add: first, this 20% rate isn’t publicly confirmed by OpenAI or Microsoft, at least in our knowledge. Second, the revenue sharing agreement is also more complex than just this number. Microsoft put a lot of money and compute into OpenAI, and in return it gets a significant ownership stake, special rights to use OpenAI’s technology, and some of OpenAI’s revenue. There also isn’t a single well-defined “end date”: some rights are set to last into the early 2030s, while other parts (including revenue sharing) continue until an independent panel confirms OpenAI has reached “AGI”.

-

Strictly speaking, a revenue share agreement is often seen as an expense that would impact gross margins. But we’re more interested in the unit economics that generalize across models, rather than those that are unique to OpenAI’s financial situation.

-

The deal was signed in 2019, a year before GPT-3 was released, and at this time it may have been an effective way to access compute resources and get commercial distribution. This could’ve been important for OpenAI to develop GPT-5 in the first place.

-

OpenAI’s main R&D spending is on compute, salaries and data. In 2025, they spent $8.3 billion on R&D AI compute, and about $1 billion on data (which includes paying for human experts and RL environments). We can estimate salary payouts in the same way we did in the previous section on inference, except we consider 60% of staff compensation rather than 40%, resulting in an expense of $4.6 billion. Finally, we add about $400 million in offices and administrative expenses, and $600 million in other compute costs (including e.g. networking costs). This adds up to about $15 billion.

-

In fact, we could be substantially lowballing the R&D costs. GPT-5 has been in the works for a long time — for example, early reasoning models like o1 probably helped develop GPT-5’s reasoning abilities. GPT-5.1 was probably being developed between August and November, covering a good chunk of the GPT-5 bundle’s tenure. But there’s a countervailing consideration: some of the R&D costs for GPT-5 probably help develop future models like “GPT-6”. So it’s hard to say what the exact numbers are, but we’re pretty confident that our overall point still stands.

-

Because OpenAI’s expenses are growing exponentially, we can’t just estimate the share of R&D spending in this period as one third of the annual total. Assuming a 2.3× annual growth rate in R&D expenses — comparable to the increase in OpenAI’s R&D compute spending from 2024 to 2025 — the costs incurred between April 16 and August 7 would account for approximately 35% of total yearly R&D expenses.

-

Are our results sensitive to whether we try to account for the costs and revenue of GPT-5.2? In December 2025, OpenAI made around $1.7bn in revenue, corresponding to about $600mn in gross profit, while in February 2026, they made around $2.1bn in revenue, or $700mn in gross profit. So in the three months that GPT-5.2 has been the default model, OpenAI has made about $2bn in gross profit. But of course, GPT-5.2 likely took some non-trivial effort to develop: GPT-5.2 has a different knowledge cutoff, a distinct knowledge profile, and was the alleged result of a “code red” effort by OpenAI to respond to competitors. If in the four months between April and August OpenAI spent around $5.3bn in R&D, in each subsequent month they likely spent at least $1bn more. So if we think GPT-5.2 took at least two additional months’ worth of R&D spending to develop, then that would put the expense to develop GPT-5.2 at over $7bn, while the gross profit of the GPT-5+GPT-5.1+5.2 bundle would currently be at around $4bn. Still not enough to break even, though depending on how tight this is as a lower bound it might get there with three more months of operations.

-

OpenAI was approaching 900 million weekly active users in December last year. For ads, they project a revenue of $2 per free user for 2026, and up to $15 per free user for 2030. Combining these numbers gives our estimate of around $2 billion to $15 billion.

-

For the investors who are willing to entertain more extreme scenarios, an even stronger effect is when “intelligence explosion” dynamics kick in — if OpenAI pulls ahead at the right time, they could use their better AIs to accelerate their own research, amplifying a small edge into a huge lead. This might sound like science fiction to a lot of readers, but representatives from some AI companies have publicly set these as goals. For instance, Sam Altman claims that one of OpenAI’s goals is to have a “true automated AI researcher” by March 2028.

About the authors