Why benchmarking is hard

Published

This post is part of our Gradient Updates newsletter, which shares more opinionated or informal takes about big questions in AI progress. These posts solely represent the views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Epoch AI as a whole.

Benchmarks play a crucial role in the AI landscape: They inform everyone, from AI researchers to the general public, about the current state of capabilities and the overall rate of progress. Third-party organizations, such as Epoch AI, independently run and collate benchmark results on a page like the benchmarking hub.

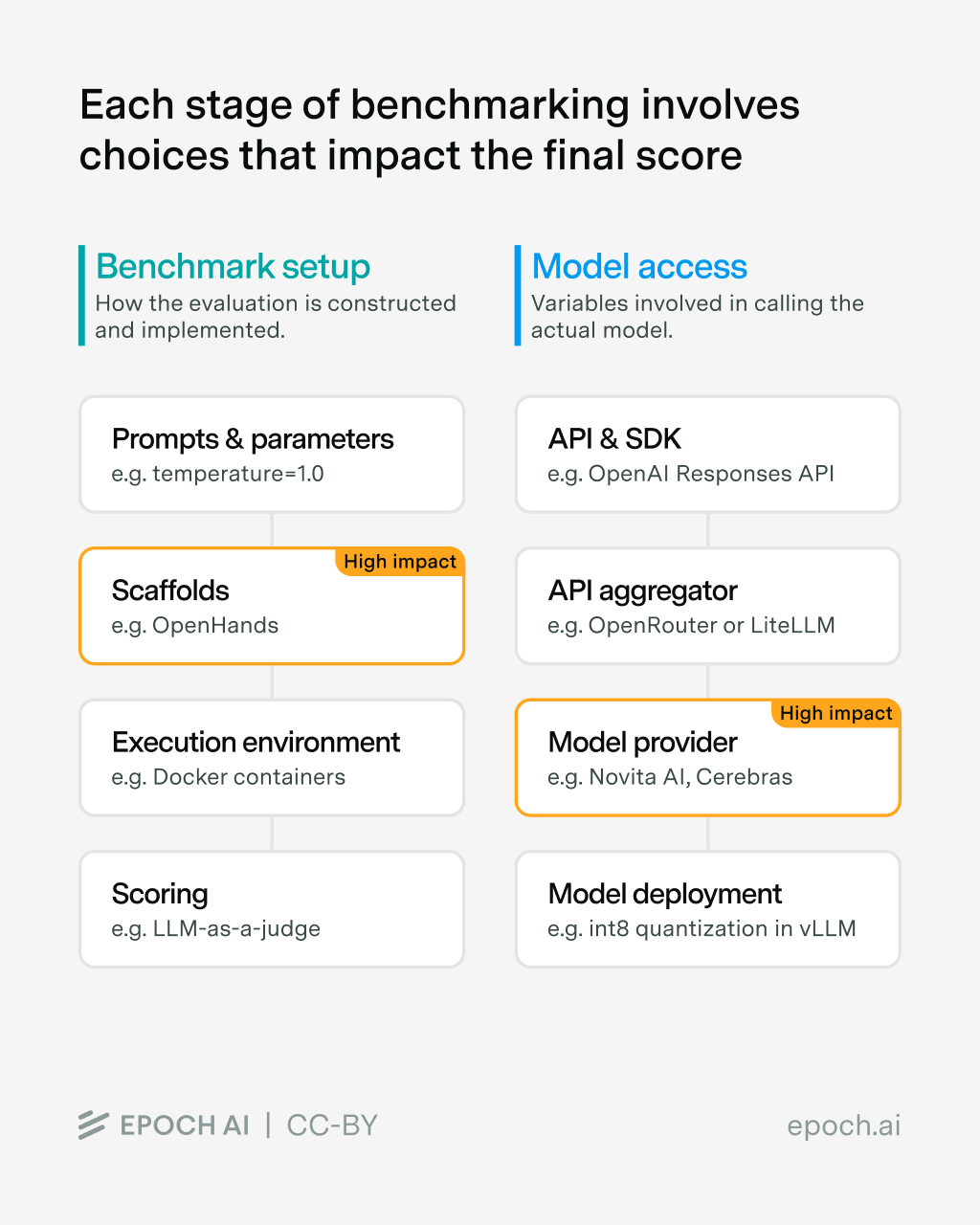

However, benchmarking isn’t easy: at each stage of the benchmarking pipeline, there are many moving parts and degrees of freedom that can affect the final result: this makes it hard to compare any two evaluation scores. Moreover, each stage can introduce bugs or mistakes that make the results costly to obtain or invalid.

In this post, we dive into the different steps of the benchmarking process, which we split into two main parts:

- Benchmark Setup: all the steps related to how the benchmark is run; for example, the prompt that describes the task to the model and instructs it to answer each question, or the methodology used to score each sample.

- Model Access: all the settings involved in accessing the evaluated model itself; for example, which API provider to call the model from.

Main takeaways

Differences in how the benchmark is set up and how the model is accessed make it hard to compare any two scores on the same benchmark. For the benchmark setup, scaffolds have a huge impact on agentic benchmarks, especially on weaker models. To access the models, API providers are commonly used. Bugs and instabilities in the chosen API provider are the biggest source of evaluation errors, which particularly affects newer models.

The Benchmark Setup

Even though everyone uses the same name for a benchmark, this does not mean that everyone runs the same version (if versioning exists), nor that they implement the benchmark in the same way. To illustrate this, we use the well-established GPQA-Diamond benchmark as an example throughout this blog post.

Prompts & Sampling Parameters

GPQA-Diamond’s initial release was accompanied by an analysis repository containing code to evaluate models on the benchmark. However, this repo is not used to run the benchmark these days. Instead, practitioners typically re-implement GPQA-Diamond’s evaluation as part of a larger standardized infrastructure to run multiple models on multiple benchmarks.

Compared to many other benchmarks, GPQA-Diamond is relatively simple to (re-)implement, with few moving parts. Indeed, it just consists of the following:

- A template which instructs the model to answer the question

- The question and four possible answers to said question

As the question and answers are fixed (and re-used through all implementations), the component that can be different is the prompt template. Evaluators must also decide on the sampling parameters that models will be run with, in particular the temperature and potential top_p or top_k parameters.Let’s look at the prompt templates and sampling parameters used by some popular benchmarking libraries:

- EleutherAI/lm-evaluation-harness:

What is the correct answer to this question:\nChoices:\n(A) \n(B) \n(C) \n(D) \nLet's think step by step:- No system message

- Default temperature is 0.0 for API-based models

- Note: There are different templates and setups depending on the evaluation and model type.

- OpenAI/simple-evals:

Answer the following multiple choice question. The last line of your response should be of the following format: 'Answer: $LETTER' (without quotes) where LETTER is one of ABCD. Think step by step before answering.\n\n{Question}\n\nA) {A}\nB) {B}\nC) {C}\nD) {D} - OpenAI/gpt-oss:

{Question}\n\n(A) {A}\n(B) {B}\n(C) {C}\n(D) {D}\n\nExpress your final answer as the corresponding option 'A', 'B', 'C', or 'D'.- No system message set

- Default temperature is 1.0 (when invoking the script via command line)

- groq/openbench:

Answer the following multiple choice question. The last line of your response should be of the following format: 'Answer: $LETTER' (without quotes) where LETTER is one of ABCD.\n\n{Question}\n\nA) {A}\nB) {B}\nC) {C}\nD) {D}- System message:

You are a helpful assistant. - Default temperature is 0.5

- System message:

So, basically everyone is doing their own thing with implementations of even simple evaluations. Fortunately, the scores reported by AI developers on GPQA-Diamond match the results of independent runs. We also tested the effect of using different prompts and temperatures with gpt-oss on GPQA-Diamond (with high reasoning effort): while we found differences between the average scores across settings (ranging from 74% to 80%), these differences were not statistically significant given the small size of GPQA-Diamond (only 198 questions). Even with the same implementation, we observe variance in this range.

While the prompt typically has a small impact for modern reasoning models on simple benchmarks like GPQA-Diamond, this was not always the case. Moreover, as we will now see, changing the prompt can have a large impact when it comes to more complex, agentic evaluations.

Scaffolds continue to have an outsized impact

As agentic evals, such as SWE-bench Verified or RLI, become more common, one component becomes increasingly important: The scaffold, i.e., the software that operates the agent, usually a CLI such as Claude Code, OpenHands, etc.

In particular, the scaffold includes all the components mentioned above, i.e., sampling parameters and prompt templates. Even more importantly, it also gives the agent a set of tools, i.e., access to specialized applications or capabilities. The exact tools and prompts change drastically depending on the chosen scaffold.

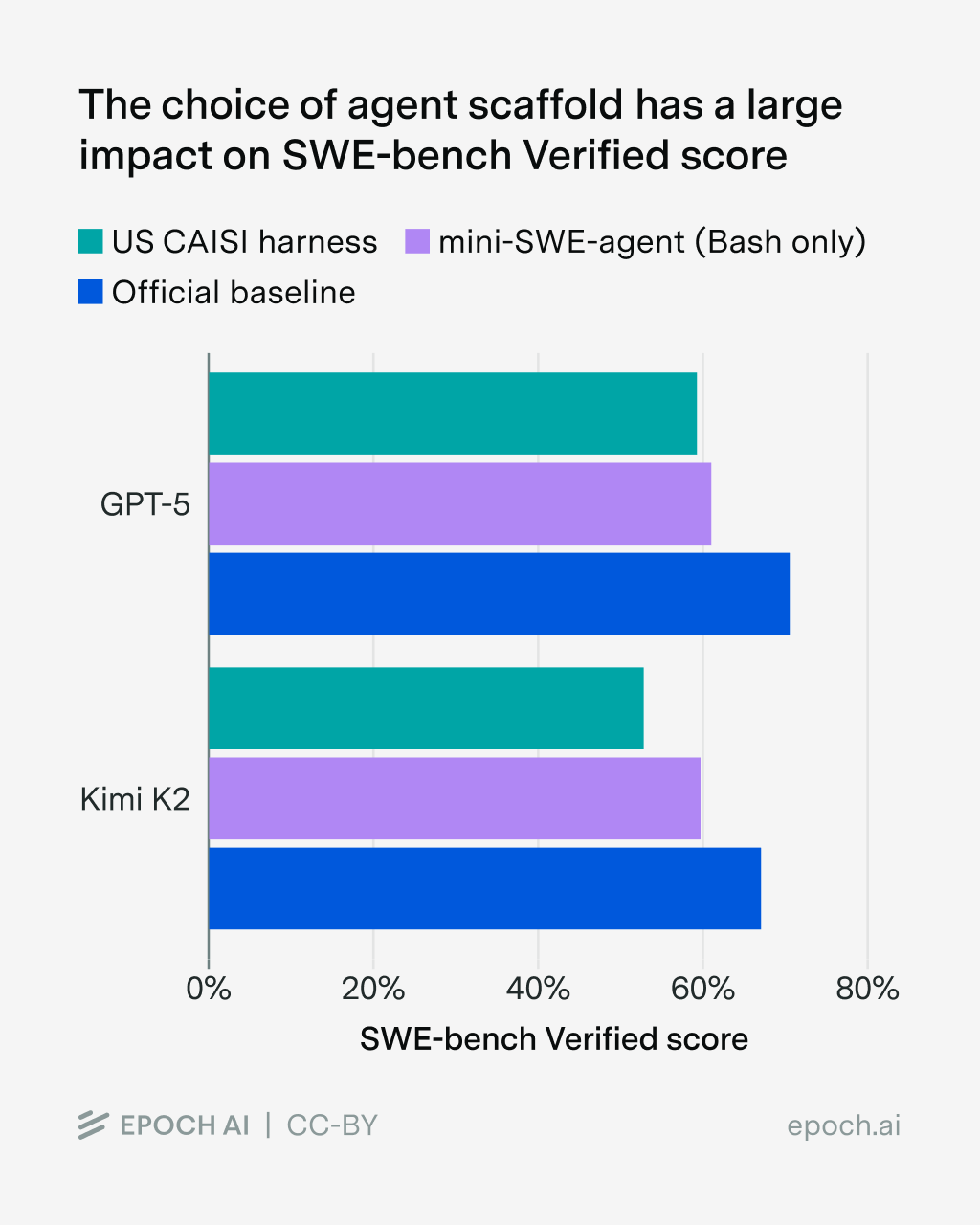

On SWE-bench Verified, a popular agentic coding benchmark, simply switching the scaffold makes up to an 11% difference for GPT-5 and up to a 15% difference for Kimi K2 Thinking. We cover the effect of the scaffold in our SWE-bench Verified review. The choice of scaffold has the single biggest impact on the overall performance.

Customizing the harness for each model risks hill-climbing on the evaluation and makes direct comparisons between models difficult. Therefore, there are two ways to evaluate agentic benchmarks: If you care about comparing models, a standardized scaffold (like mini-SWE-agent) is usually enough. On the other hand, assessing frontier capabilities requires the usage of leading products like Claude Code. Both these choices come with very obvious trade-offs, especially in terms of reproducibility, and require additional engineering efforts.

Execution Environment

The LLM, especially in agentic evaluations, has to operate in an execution context or environment. Concretely, this means things like the virtual machine for computer use evals, or the Docker container for coding evals. Creating and maintaining these environments is hard: OpenAI only ran 477 of the 500 problems in SWE-bench Verified in their o3 and o4-mini evaluations due to infrastructure challenges.

Sometimes the environments contain critical errors, which means that agents are able to hack the eval (or are unable to fulfill a task due to bugs). This is especially true for evaluations which allow the agent to search the web for information: In the worst case, the agent is able to find the original dataset or sites which re-host parts of a problem. As the open web is so vast, it means that a banlist of domains needs to be continuously maintained.

The impact of the environment is moderate compared to the scaffold. Typically, the environment has little impact on the results, unless the agent is able to hack a large percentage of samples or if the environment is actually broken.

Scoring

The final step of every evaluation is to score the given sample. To extract and score the answer, implementations of GPQA-Diamond typically use regular expression parsing, which can be tweaked to catch all possible edge cases and model answers. Coding benchmarks such as SWE-bench Verified get scored by using a test suite, which runs the model-generated code.

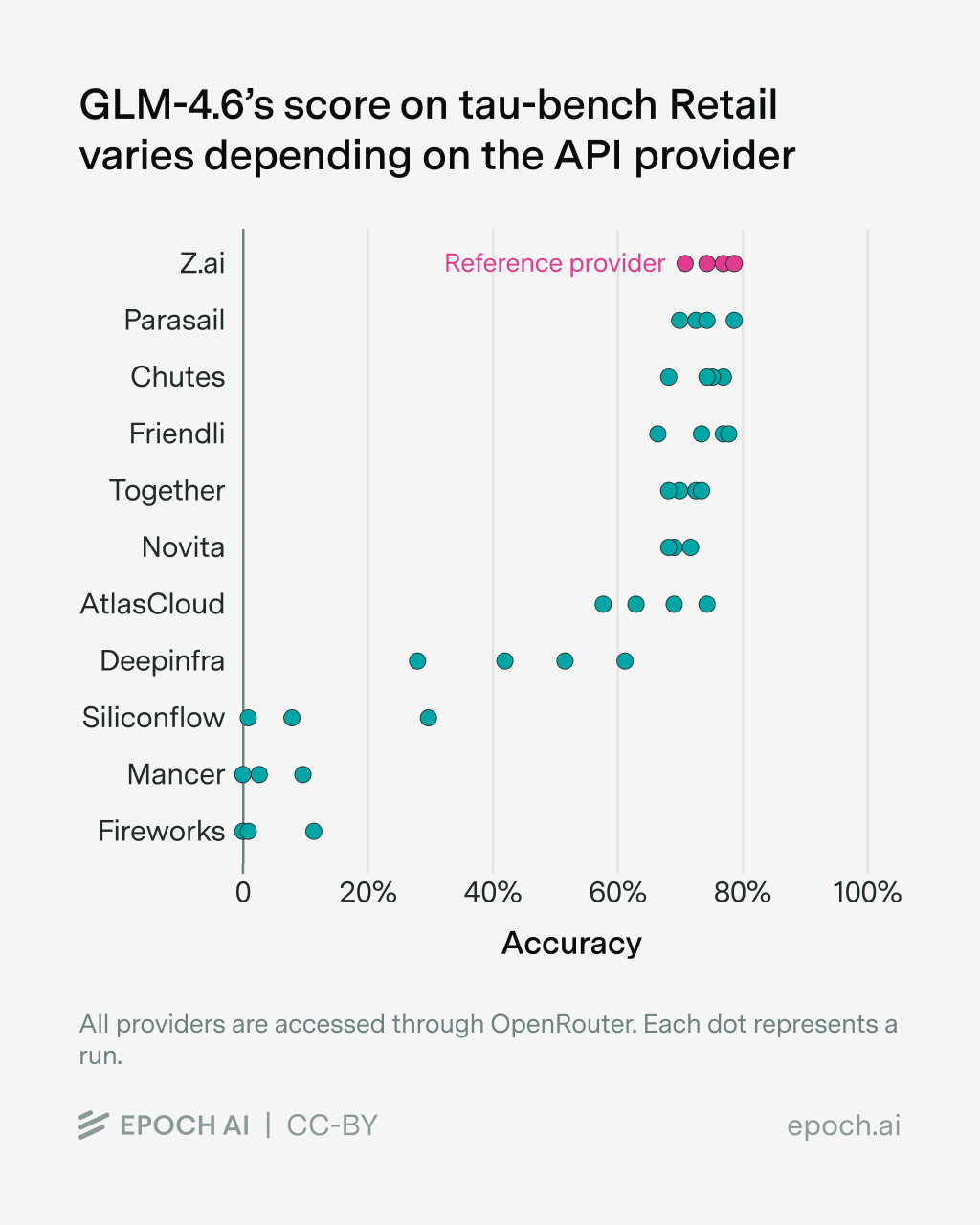

Other evaluations, such as SimpleQA, use a second LLM to extract the answer and grade its correctness; while evals like tau-bench use a second LLM to simulate a user that the evaluated model interacts with. The choice of this second LLM can have a sizable impact on the benchmark score.

Model Access

While the choices made when implementing the benchmark are within the control of the evaluator, they are not the only source of variance, as the models themselves have to be accessed in some way.

API & SDK

The prompt first gets sent through the SDK and API endpoints that are called during the evaluation run. Using the standard OpenAI ChatCompletions makes it easy to use a lot of different models, as all services and providers offer an OpenAI-compatible endpoint.

However, this might leave performance on the table – OpenAI reports up to 3% improvements on SWE-bench Verified by using their Responses API, while other providers, such as Anthropic, only offer a subset of features in their OpenAI ChatCompletions compatible endpoint. Minimax reports an astronomical 23 percentage point difference in performance on tau-bench when using their API implementation compared to the standard ChatCompletions API. Therefore, to avoid undereliciting models’ capabilities, it’s important to use the correct SDK.

API Aggregator

Of course, implementing all providers yourself is a tedious task, and there are solutions for this, such as LiteLLM or Inspect AI, which offer a unified interface to interact with any model from any provider. Aside from this, services such as HuggingFace Inference Providers or OpenRouter offer a unified interface to various models and their providers. Naturally, they have to build a layer on top of the APIs, which may result in new bugs1.

Model Provider

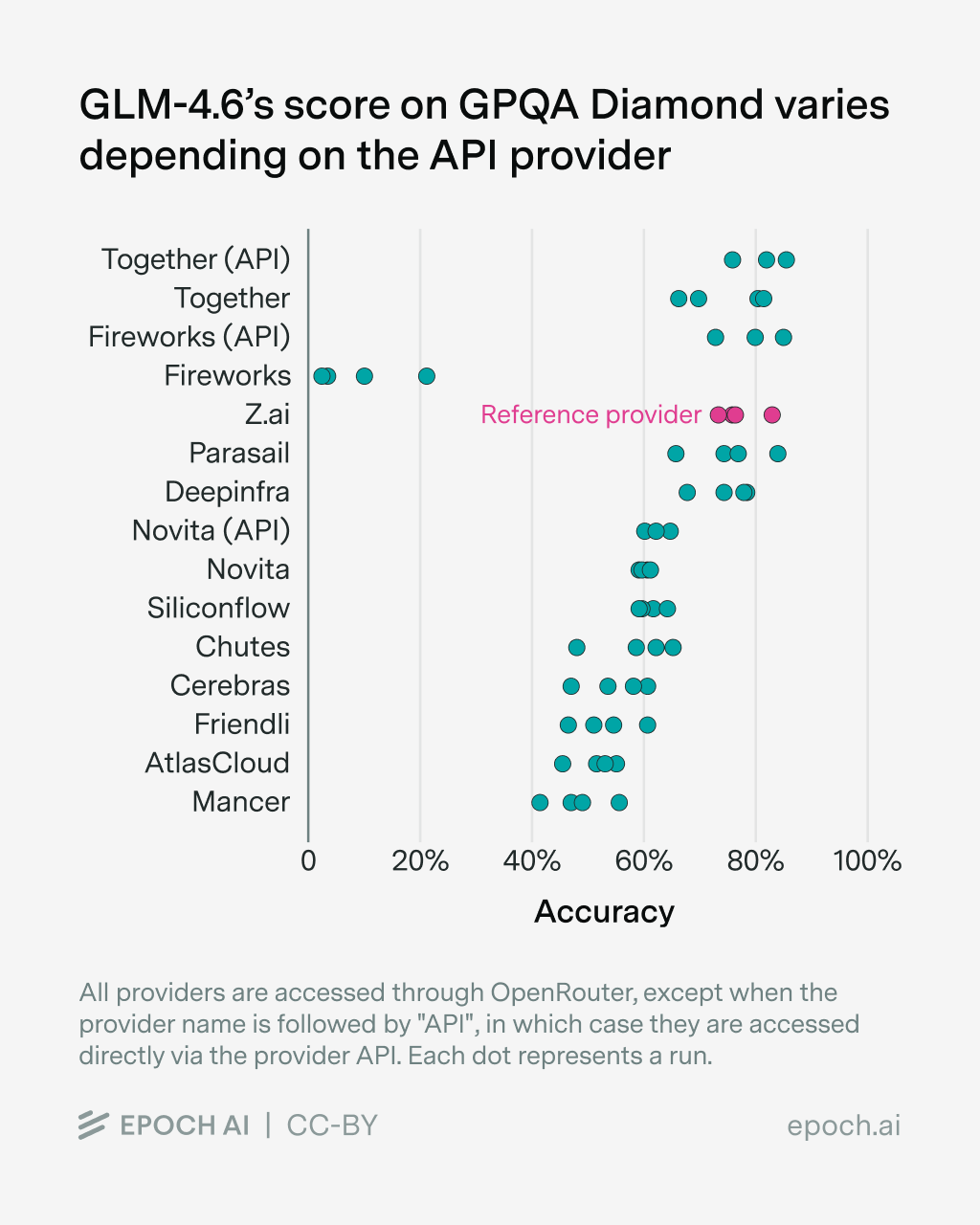

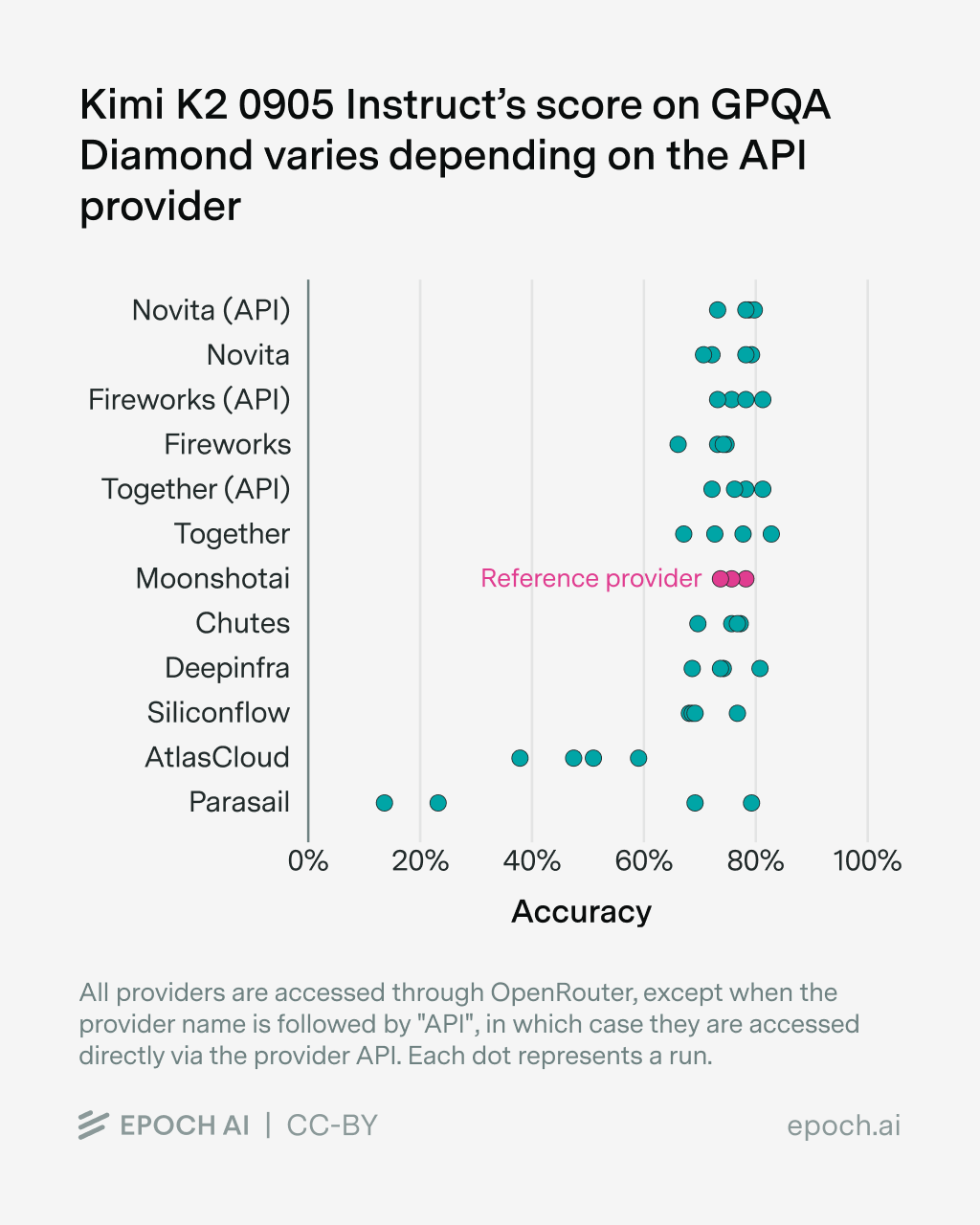

The biggest factor of variance in evaluation results, however, is the provider of the model itself, especially for open models. The choice of provider impacts both which sampling parameters are supported, as well as the downstream performance.

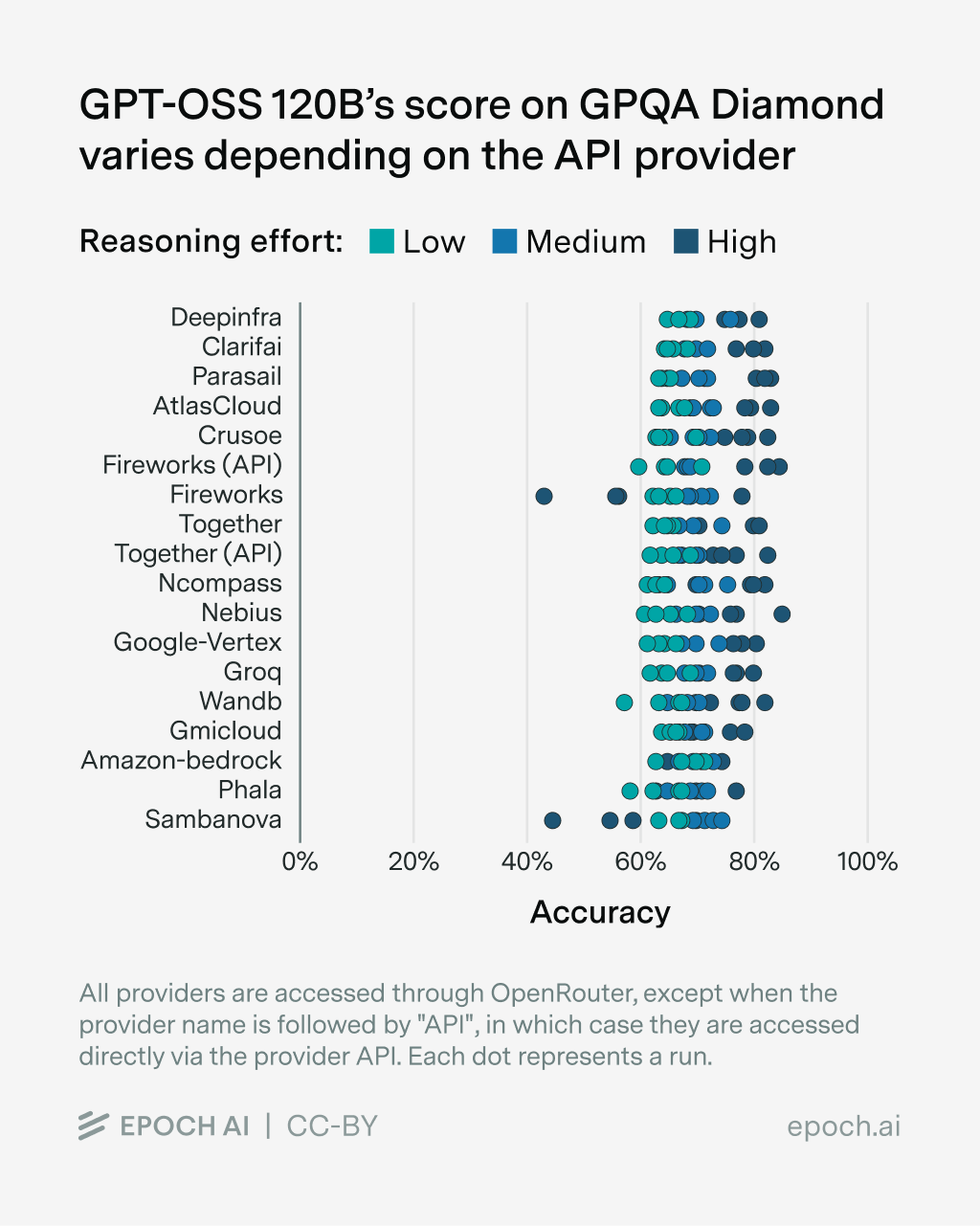

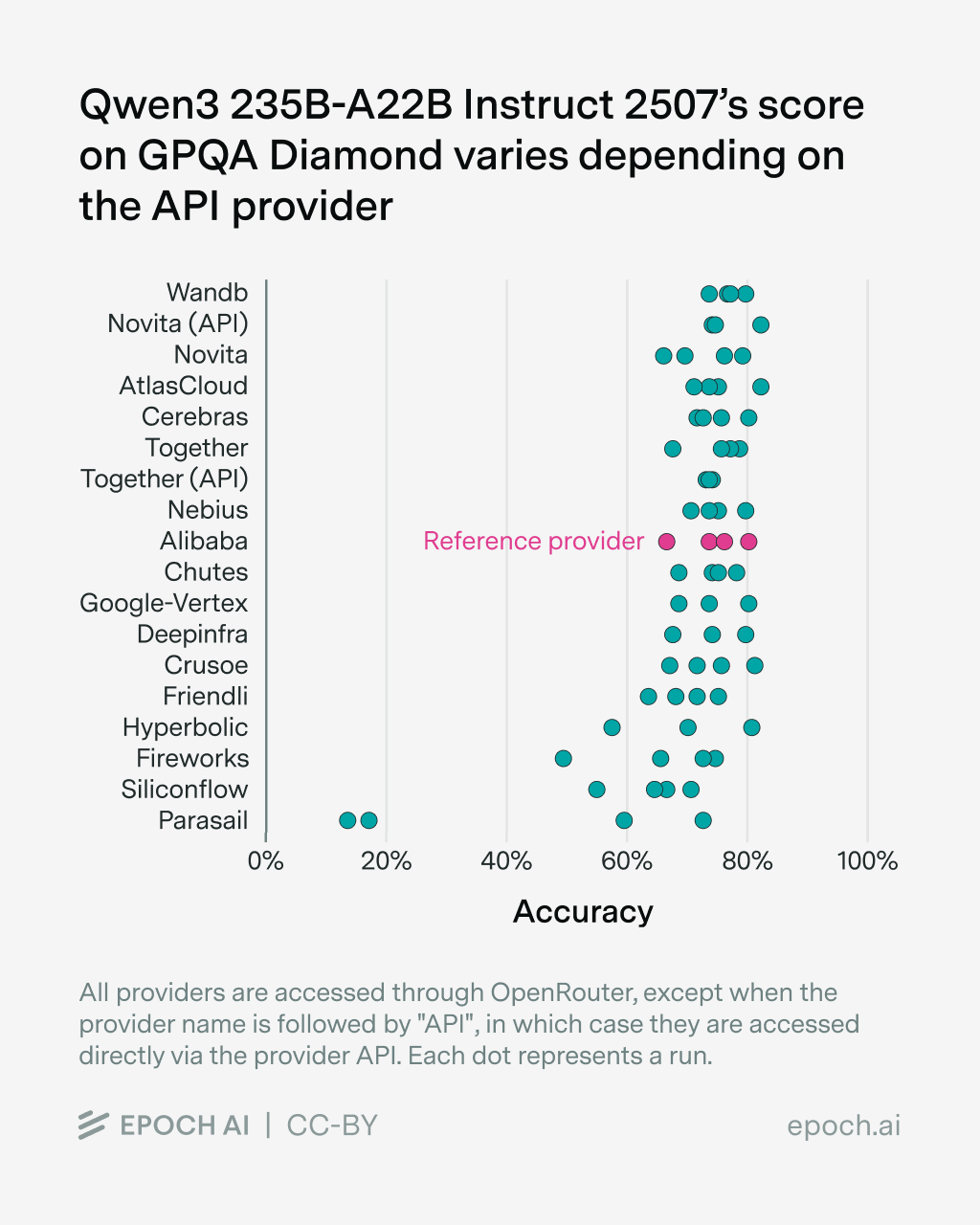

To test the effect of the API provider ourselves, we ran several popular open models on GPQA-Diamond and averaged their scores over 4 runs2. We retry each sample up to three times in case of errors and score (API) errors as failed samples3.

We find differences in benchmark scores depending on the model provider for all tested models, though the effect size varies between models. More results can be found in the Appendix4. We observed various sources of error:

- Some providers return RateLimitErrors, especially when accessing GLM-4.6 over OpenRouter. The providers mainly affected are Fireworks (via OpenRouter), GMICloud, Mancer, Parasail, DeepInfra, SiliconFlow. As these samples get scored as failure, the scores for the corresponding provider are affected substantially.

- Some providers return empty or cut-off responses, although the

max_tokensare not reached. This includes AtlasCloud, Mancer, Fireworks (via OpenRouter). - Some providers have lower

max_tokensthan advertised, resulting in cut-off responses, even though a higher limit was set via the API request. This affects SiliconFlow, Friendly and Cerebras. - Some providers have

max_tokenslimits which are lower than needed to evaluate the corresponding model. These providers were dropped completely for the given eval. An example of this is gpt-oss 120B, which needs more than 32K tokens to properly evaluate GPQA-Diamond; providers such as Novita, SiliconFlow or Cerebras have lower limits. - A few responses run into a timeout, which is set to 10 minutes by default.

- Rarely, model responses run into “doom loops”, i.e., the model re-generates part of its response endlessly, until it reaches the

max_tokenslimit. - For GPT-OSS, one provider (Amazon Bedrock) does not get the correct

reasoning_effortfrom OpenRouter, resulting in the same performance for all three levels of reasoning.

Aside from these errors, we find that providers are noticeably worse at serving newer models, in our case GLM-4.6, compared to established models such as Qwen3. This is consistent with other model releases, which are accompanied by bugs that are then fixed over time. However, independent benchmark organizations want to evaluate new models as soon as possible.

The selection of an appropriate provider has the biggest impact on model performance. The model developer usually hosts their own API, which could serve as a reference. However, this hosted API often offers worse data security guarantees than third-party APIs, so evaluators might prefer not to use it for private benchmarks.

In practice, this means that those running the benchmark have to experiment a lot, trying to replicate known scores with third-party APIs5 and hope that it is implemented correctly. This is a laborious and costly effort and one of the main reasons evaluations (of open models) take a lot of time.

Model Deployment

Going under the hood, there are multiple reasons why the performance for a model differs from the reported score or between different model providers. They can range from software, such as a different inference engine (vLLM, SGLang, private forks), bugs in the reference implementation, or outdated chat templates, down to the used hardware and the corresponding deployment. Yes, even using different parallelism setups, i.e., how you distribute and split up a model over multiple GPUs, has a measurable, but small, impact.

Conclusion

Running benchmarks isn’t easy, and there are a lot of variables that affect the headline numbers you will see on a graph or in a table. A lot of these variables don’t seem to matter in isolation. However, they can add up quickly over the whole stack, which results in numbers that differ substantially from the scores reported by model developers.

Some of these variables, such as the used prompts and scaffolds, are in the control of those who create, re-implement and run the benchmark, while others aren’t. This is especially true for the model access by using (third-party) APIs, which slows down lower resource actors, such as hobbyists or academics. Errors in evaluations also make it hard for others, from AI researchers to decision makers and the general public, to accurately assess the current progress of capabilities.

OpenRouter graciously sponsored the credits for the experiments on their platform. We maintained full editorial control over the output.

Appendix

We evaluated GPT-OSS 120B at all three reasoning levels, GLM-4.6, Qwen3 235B-A22B Instruct 2507, Kimi K2 Thinking and Kimi K2 0905 Instruct on GPQA-Diamond while varying the API provider and keeping everything else constant.

We evaluated GLM-4.6 (as both the agent and the user model) on tau-bench Retail while varying the API provider (keeping the same provider for both agent and user), while keeping everything else the same.

We use this implementation for GPQA-Diamond and this re-implementation of tau-bench. We also make all the data for the analysis available under this link.

GPT-OSS 120B

Kimi K2 Thinking

Qwen3 235B-A22B Instruct 2507

GLM-4.6

Notes

-

This particular bug has since then been (mostly) fixed. ↩

-

Usually, benchmarks such as GPQA-Diamond are run between 8-32 times and then averaged. We opt for 4 runs for cost reasons. We use this implementation for GPQA-Diamond and this re-implementation of tau-bench. ↩

-

Of course, this is not the policy we use when evaluating models on the Epoch AI Benchmarking Hub, where except in pathological cases we ensure that there are no more errors before reporting a score. However, we believe this convention makes sense for the purpose of evaluating providers and how they complicate the benchmarking process. ↩

-

We also make all the data for the analysis available under this link. ↩

-

While there are methods to detect levels of quantization and possibly deployment bugs, they require a correctly set-up local deployment, knowledge of the inference engine of the provider as well as exposed sampling parameters such as the seed (which not all providers offer). ↩