How far can decentralized training over the internet scale?

Published

This post is part of our Gradient Updates newsletter, which shares more opinionated or informal takes about big questions in AI progress. These posts solely represent the views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Epoch AI as a whole.

Previously, I discussed decentralized training in the context of hyperscalers. Microsoft, Google and other giants are building interconnected gigawatt scale datacenters, which could be used to train models at an unprecedented computational scale. The decentralization could sidestep the difficulty of securing 10 GW of power in a single location by splitting one massive run into ten more manageable gigawatt-scale blocks.

But when people think of decentralized training, they don’t first think of gigantic datacenters, owned by the same company, training models across large distances. Instead, they imagine thousands of small datacenters, or individual consumers, pooling their spare compute over the internet to orchestrate a training run larger than any single actor could manage alone.

Many companies are pursuing this vision: Pluralis Research, Prime Intellect and Nous Research have already successfully decentrally trained models at scale. But in practice, training decentrally over the internet has lagged far behind more centralized training. Even their largest models (Pluralis’ 8B Protocol Model, Prime Intellect’s INTELLECT-1, and Nous’ Consilience 40B) have been trained with 1,000x less compute than today’s frontier models (such as xAI’s Grok 4).

And, importantly, many proposals for monitoring and regulating AI depend on internet decentralized training continuing to lag far behind the frontier. The compute is easy to track when it’s centralized, either in a few massive data centers or many smaller (but still large) data centers connected via a dedicated network of fiber optic cables. As long as it only makes economic sense for frontier models to be trained thusly by a handful of the biggest companies, governments can relatively easily regulate them.

However, if that assumption – that training over the internet across thousands of computers isn’t feasible – breaks, then regulation might be left scrambling to catch up.

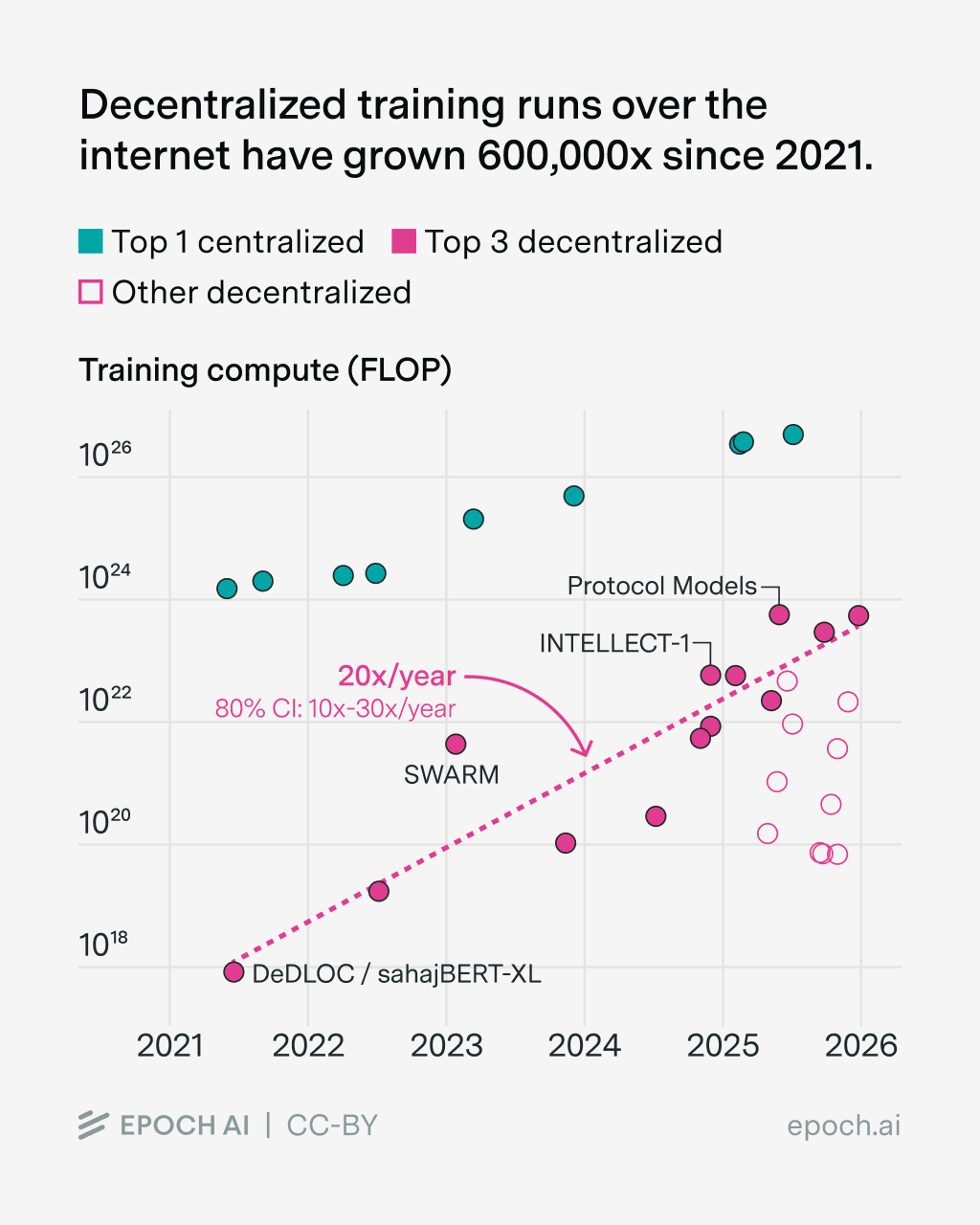

In this article, I review and critically examine the state of the field of decentralized training over the internet. I conclude that while decentralized training is growing fast (around 20x per year) and technically feasible at frontier scale, it’s unlikely that decentralized developers will amass frontier amounts of compute this decade.

Is decentralized training over the internet feasible?

Decentralized training over the internet is a strictly harder engineering task than centralized development.

The three big additional challenges that decentralized training poses are: low-bandwidth communication, managing a network of heterogeneous devices with inconsistent availability, and trust and coordination issues. While important, I believe the latter two won’t ultimately impede training at scale.1

Low bandwidth poses a more important problem. Typical internet upload bandwidths for consumers are around 60 Mbps. If using naive data parallelism to distribute training across nodes with this much bandwidth, it would take 5,000 years to train a DeepSeek v3 style model with 671B parameters.2

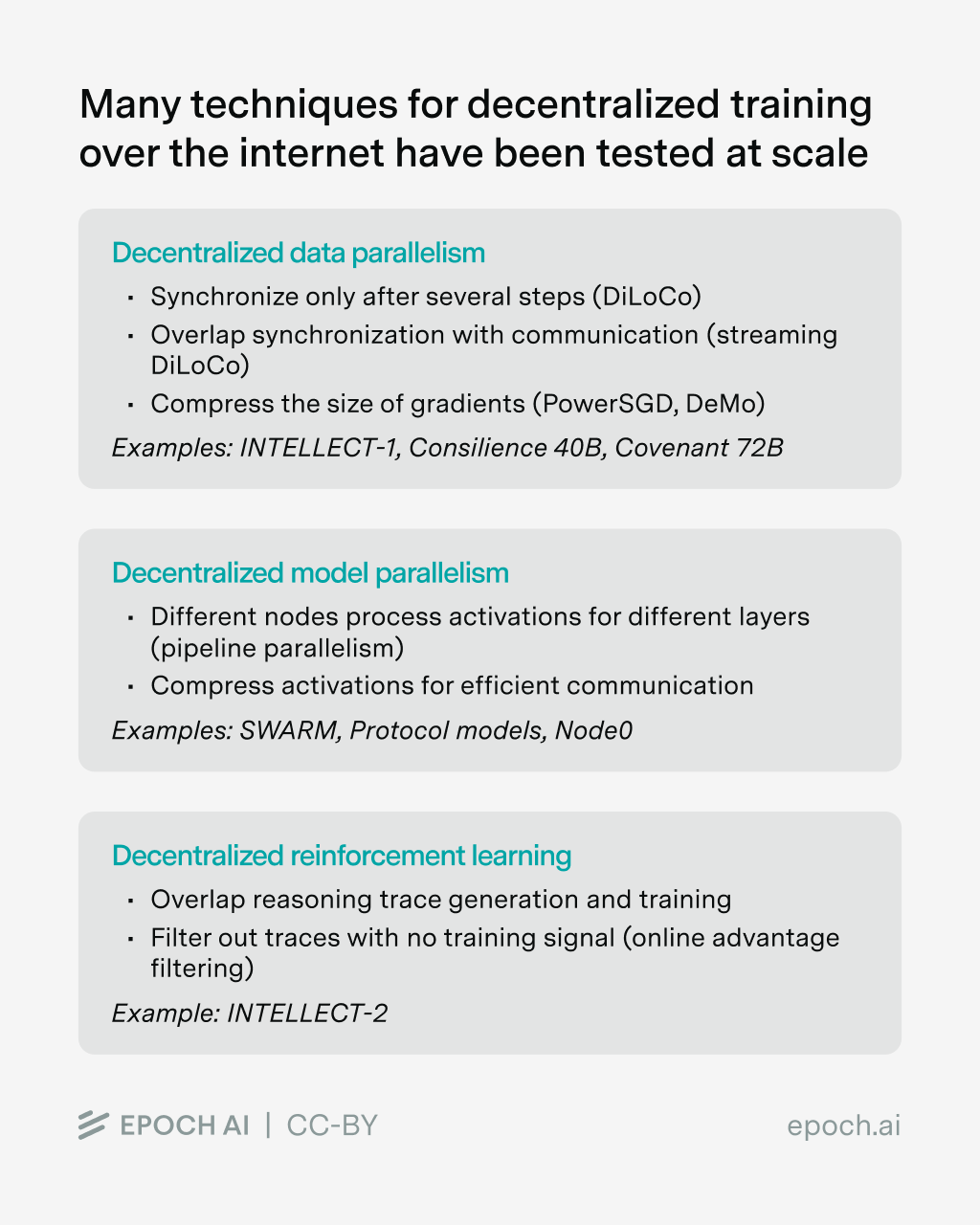

But Pluralis, Prime Intellect and Nous Research have already trained (and postrained) models with billions of parameters. The key is in a family of techniques to reduce bandwidth requirements, and enable different kinds of decentralized training: data parallelism, model parallelism, and RL training.

Decentralized data parallelism

When using data parallelism to distribute training across multiple data centers, we have the centers communicate once every batch to synchronize gradient updates.

When training over the internet, that communication cost would be prohibitive. For instance, with typical upload speeds reaching around 60 Mbps, the largest model we could train while keeping synchronization times under ten minutes would be a rather small 600M parameter model with 32-bit gradients.3

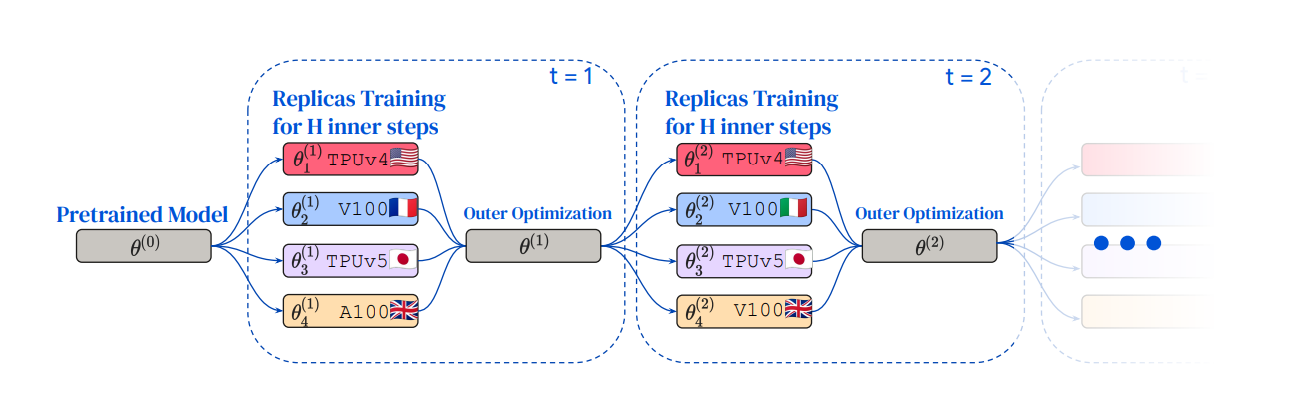

One solution is to reduce the frequency with which each data center or individual computer (each node) talks to each other. So instead of synchronizing weights with every batch, we let each node process multiple batches independently (these are called “inner steps”), then aggregate the cumulative gradient updates each node has taken in the synchronization step (an “outer step”).

Figure from Douillard et al. (2023). Each node holds a replica of the model, and trains independently for a number of inner steps before synchronizing across nodes.

This process was demonstrated in the DiLoCo paper by Douillard et al. (2023), building on previous work, such as that by Sticht et al. (2018). This process is not equivalent to the usual training process, and as such it can harm performance. However, the DiLoCo authors find that they can conduct training with up to 500 inner steps with only a small reduction in performance, for a 500x reduction in bandwidth requirements.

One key weakness of DiLoCo worth stressing is that the performance is reduced as the number of nodes increases. In particular, increasing from 1 to 8 nodes is equivalent to a 1.5x decrease in training compute (see table 4 and 11 of Charles et al, 2025). Naively, this suggests that scaling to 10,000 nodes would require 6x as much FLOP as centralized training for the same performance. This is not trivial, though it can be compensated for by training for longer, or with larger clusters.

To further reduce the strain on the bandwidth, we can reduce the size of the gradients. The main way this is done in practice is quantization, where the gradients are communicated on a lower bit precision. By reducing the gradients to 8-bits, as in the INTELLECT-1 run, or to 4 bits, as in the Streaming DiLoCo paper, we can reduce bandwidth requirements by 2-4x compared to typical 32-bit gradient synchronization. Some even have experimented with 1-bit gradient updates (Tang et al, 2021; Lu et al, 2022), though their efficacy is yet to be shown at scale.

Another type of compression is sparsification, in which only the most significant (top-k sparsification) or a random subset of the gradients (random sparsification) are communicated in each round. The decoupled momentum (DeMo) optimizer by Nous Research is a variant of this, in which larger updates are prioritized, while smaller gradients are accumulated until they reach a threshold of significance.

Both quantization and sparsification degrade the quality of the gradients communicated. To fight this, one technique often used is error feedback accumulation: the difference between the gradients computed and communicated is stored, to be communicated in future updates.

These methods can be combined. CocktailSGD experiments with finetuning models with up to 20B parameters combining quantization and sparsification. MuLoCo further combines these techniques with DiLoCo and a Muon optimizer. SparseLoCo takes a similar approach – and it is now being applied at scale as part of the Covenant72B decentralized training run by Covenant AI.

We can optimize DiLoCO further. In the Streaming DiLoCo paper, Douillard et al (2025) explain how to sequence synchronization on different subsets of parameters while training. This enables overlapping computation with communication, which together with DiLoCo and 4-bit gradient quantization, reduces bandwidth strain by 100x compared to naive data parallelism.

Decentralized model parallelism

While most decentralized training today leverages data parallelism, others — notably Pluralis Research — have experimented with model parallelism.

In model parallelism, the parameters of the models are themselves split between nodes. This has one major advantage: since each node doesn’t need to hold the whole model, nodes with small memory such as consumer GPUs can be part of the network without constraining the model size.

For instance, the SWARM parallelism paper by Ryabinin et al (2023) proposes decentralized pipeline parallelism, where nodes process subsets of model layers, propagating activations and gradients between them. The paper notes the square-cube law: as we increase the model dimension, communication scales linearly, but compute scales quadratically. This means that larger models suffer less from the communication overhead, making pipeline parallelism a practical choice in low-bandwidth setups.

Pluralis’ Protocol Models further optimize pipeline parallelism by constraining each layer’s activations to a small subspace, for up to a 100x reduction in size. This allows them to train a 8B Llama-like model in a decentralized fashion, as well as a 7.5B model through a volunteer network.

Other forms of model parallelism have been experimented with. Prime Intellect used pipeline parallelism for SYNTHETIC-2 – a decentralized synthetic data generation project. The learning@home paradigm by Ryabinin and Gusev (2020) and the SPES protocol by Zhang et al (2025) splits different experts from a mixture-of-experts (MoE) across different nodes for training and inference. Pluralis has also experimented with decentralized context parallelism in Ramasinghe et al (2025), in which different nodes process different parts of a sequence, and need to coordinate to compute the attention context.

Decentralized RL training

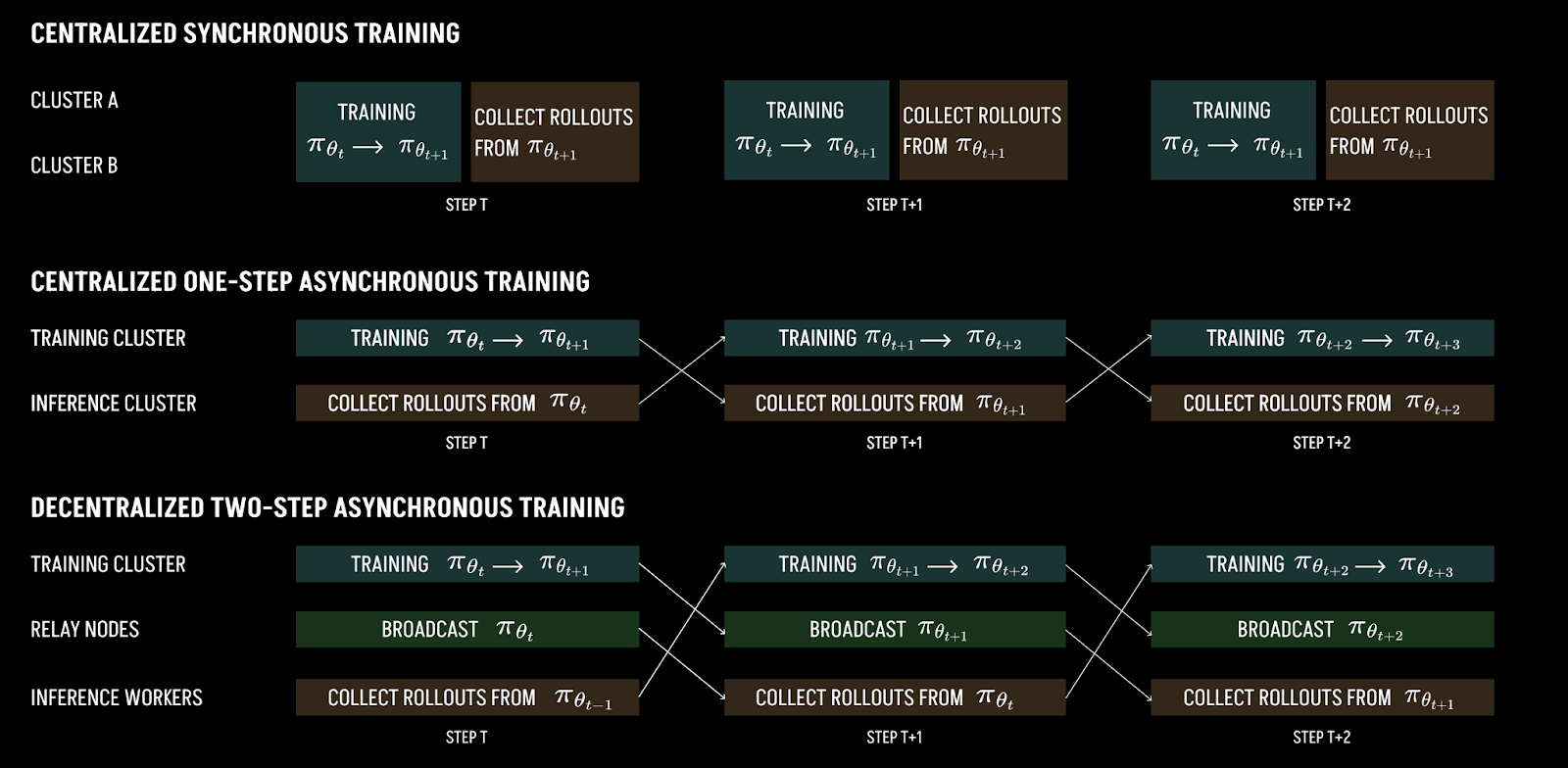

Since last year we have seen a rise in the prominence of RL postraining methods, often called reasoning training.

In a typical RL training scheme (such as GRPO) we generate many reasoning traces with the latest model checkpoint. Each trace is automatically scored relative to the other traces in the group. These scores are used to update the model weights, increasing the relative log-likelihood of the highest scoring traces relative to the worse ones.

In asynchronous RL, we allow the trace generation to be done with an outdated version of the model, often 2 to 5 steps behind the current checkpoint. This has the advantage that we can overlap communicating the updates with generating the traces, mitigating communication bottlenecks.

Figure from the INTELLECT-2 release post, illustrating asynchronous RL training.

The largest decentralized RL training run to date is INTELLECT-2 by Prime Intellect, which coordinated the output of over 800+ nodes to generate traces and post train a QwQ-32B base model using asynchronous RL.

In synchronous RL, the burden of compute is tilted more towards inference than in traditional pretraining. The ratio of compute in FLOP is the same — a forward pass to compute the activations is matched by twice as much compute in the backward pass to compute the gradients — but trace generation is memory-bound, making it take more GPU-hours than the backward pass. In asynchronous RL, because the forward pass must be repeated with up-to-date model weights, the amount of inference compute is even higher.

INTELLECT-2 employs Online Advantage Filtering to shift the burden even more towards inference: groups of reasoning traces with no advantage are discarded, since they generate no training signal. This allowed for a decentralized inference network that used 4x more compute than the training nodes.

More recently, Prime Intellect unveiled their INTELLECT-3 run. This was a larger scale finetuning and asynchronous RL post-training run, albeit run in a centralized setting. The success of this run paves the way for larger decentralized RL training runs in the future.

Putting it all together: decentralized internet training at frontier scale is likely feasible

My overall impression is that all the techniques we have discussed could be combined to train much larger decentralized models than exist today.

Taking for example the INTELLECT-1 model, one of the largest decentralized pretraining runs to date. It is a 10B parameter model trained on 1T tokens, which amounts to 6e22 FLOP. And it essentially only leveraged two basic decentralized training techniques to manage bandwidth: DiLoCo with 100 inner steps per synchronization, and 8 bit quantization.

If we further quantize to 4-bits and apply 25% sparsification as in SparseLoCo, we would theoretically be able to train a model 8x larger, which per Chinchilla scaling would allow for training runs with about 64x more compute. A similar strategy is how Templar is currently decentrally training a 72B parameter model.

Going further, during the INTELLECT-1 training run, the contributor nodes ran independently for about 38 minutes before synchronizing for 7 minutes. Applying streaming DiLoCo could hide a large part of that communication. With an optimized interleaving schedule, this could allow for training a 2x larger model, i.e., 4x more compute.4

As we alluded to, many of these techniques moderately harm performance. While not trivial, the performance reduction looks modest in practice. For example, based on the evaluations results reported by developers, INTELLECT-1 would achieve an Epoch Capability Score (ECI) around 98. This is e.g. similar to Qwen2.5-Coder 1.5B, which was also trained with a similar amount of compute around the same time INTELLECT-1 was released.

My conclusion is that there exists plenty of room to experiment with bandwidth reduction techniques, such that much larger training runs are technically feasible over the internet. These techniques compromise somewhat on quality compared to centralized training, and many are not yet tested at scale nor in combination with each other, so not all will work. But there are enough avenues that I am optimistic bandwidth won’t limit the scale of decentralized training anytime soon.

Can decentralized developers amass the necessary compute?

While technically feasible, reaching the frontier of compute requires an astounding amount of resources.

The largest decentralized pretraining runs to date are INTELLECT-1, Protocol Model 8B, and Consilience 40B. These span the 6e22-6e23 FLOP range — 1000x less compute than what we estimated was used to train the largest models today, such as Grok 4.

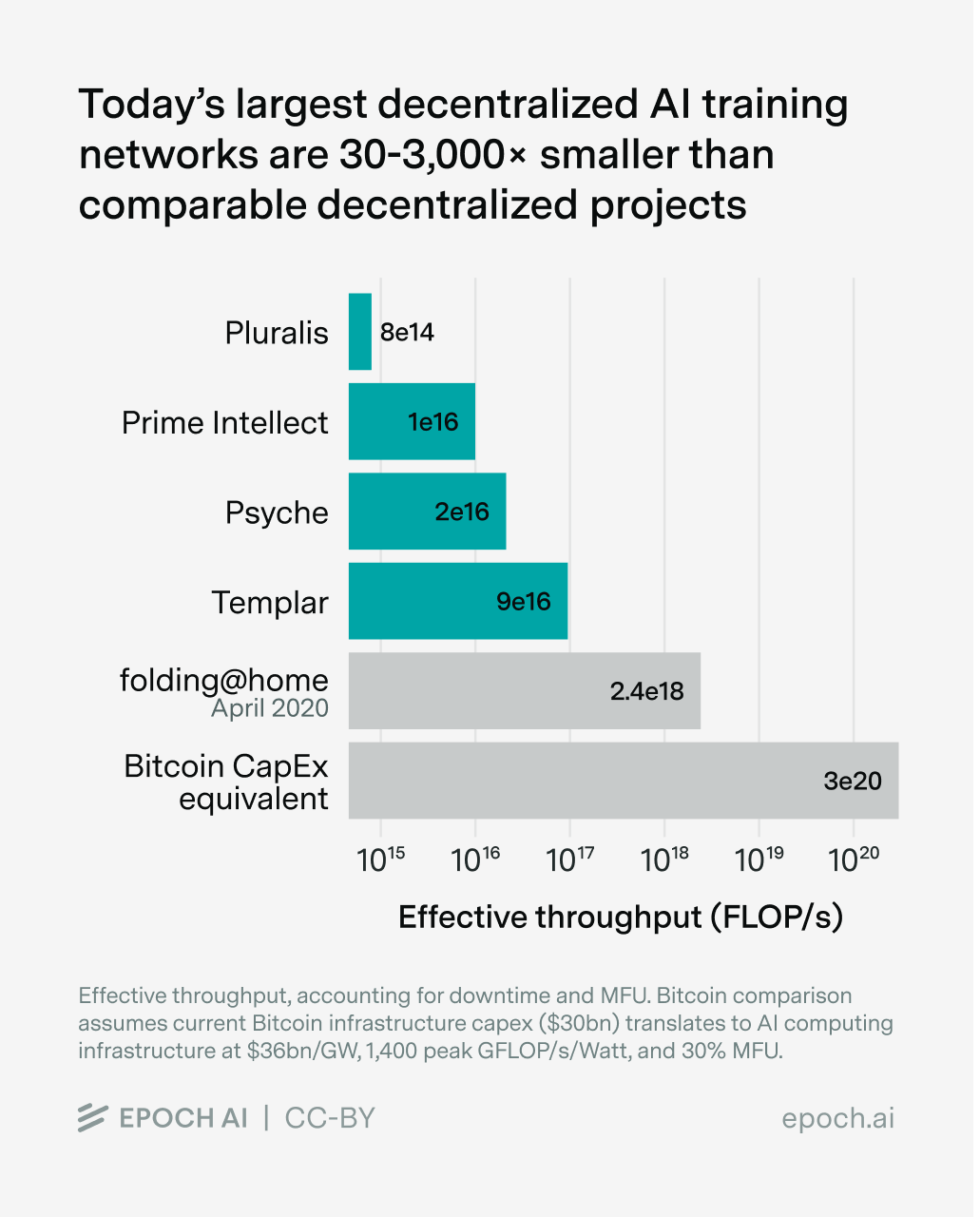

In order to train them, decentralized networks have been set up, such as Prime Intellect’s platform, the Psyche Network by Nous Research, and the Pluralis dashboard. The largest such active network we’ve found is Covenant AI’s Templar, which is currently achieving an effective throughput of 9e17 FLOP/s respectively. This is about 300x smaller than frontier AI datacenters today, which have a theoretical training throughput of about 3e20 effective FLOP/s (eg the Microsoft Fairwater Atlanta site, assuming 30% MFU and 8-bit training).

While they are relatively small for the moment, it is worth appreciating that the scale of decentralized training runs has grown astoundingly fast. Since 2020, we have seen a 600,000x increase in the computational scale of decentralized training projects, for an implied growth rate of about 20x/year.

This is a rate of growth that even dwarfs the rate of growth of frontier AI training, recently growing as 5x/year. If both trends held, it would take five and a half years for decentralized training to catch up to the scale of centralized training.

But can this growth be maintained? We look into three reference classes that inform the largest scale decentralized training could reach: the largest volunteer computing project to date, the scale of the largest cryptocurrency networks, and an estimate of the amount of spare compute capacity today.

Starting with the last one: today, there are about 15.7M H100-equivalents of AI compute across NVIDIA, TPU, and Trainium devices. In comparison, the largest datacenters today, such as Anthropic’s New Carlisle site, host about 300k H100-equivalents, ie less than 2% of the AI compute stock total. A significant fraction of total compute could be idle for long periods, making it available for decentralized internet-based training.

So in theory, there exists a massive amount of AI compute which could be leveraged for decentralized AI training at a larger scale than has been achieved to date.

However, leveraging that amount of compute is likely unfeasible. Decentralized training project will only be able to access a fraction of existing computational resources. Determining exactly how much is complicated.

One possibility is by comparison to the largest decentralized computing projects. The largest collaborative computational project to date is folding@home, a volunteer computing network for simulating protein dynamics relevant to drug discovery. At its peak, folding@home attained a peak throughput of 2.43e18 FLOP/s – more than the Top 500 supercomputers combined at the time. At 2.43e18 FLOP/s, a decentralized network would be able to conduct a 2.43e18 FLOP/s x 100 days ≈ 2e25 FLOP training run. Not enough to reach the frontier today, but similar in scale to the previous generation of frontier AI models, including eg Llama 3, GPT-4, Gemini 1.0 Ultra and Claude 3 Opus.

Alternatively, we could compare to Bitcoin, whose decentralized hashing network encompasses $30 billion of existing infrastructure.5 For AI, that would be about enough for a gigawatt scale site, which could be used to train models at the 3e27 FLOP, still enough for a frontier scale run today.

The folding@home and Bitcoin reference classes suggest that today’s largest decentralized training networks (such as Prime Intellect’s) could be expanded 30-3,000x in scale, enough to train models on 50-5,000x more compute than today, in combination with longer training durations. This suggests the current fast rate of growth of decentralized training runs could last 3 to 6 years.

Conclusion

Decentralized training over the internet has captured the imagination of many developers, due to its potential to leverage large amounts of idle compute worldwide.

Technical feasibility is an important concern. But while bandwidth imposes an important technical challenge, enough techniques are being experimented with that I am optimistic about the prospects of much larger models being trained.

Frontier companies are unlikely to pursue internet decentralized training, since they can afford to build more efficient data centers. So internet decentralized training is likely to remain the domain of smaller companies focused on decentralized networks.6

Hence, my uncertainty is about the compute such decentralized networks will be able to muster. They have grown remarkably quickly so far, though they are still far from the frontier. Looking at past volunteer computing projects such as folding@home, and the scale of decentralized computing networks such as Bitcoin, I see room for decentralized training networks to grow 30 to 3,000x in scale in coming years. If unimpeded, at the current rate of growth, we won’t see decentralized training runs catch up to the frontier of training in scale this decade. Even if they did, the performance loss from the bandwidth reduction techniques would set them back compared to centralized training.

But decentralized training could still be a very important part of AI. To the extent that decentralized networks remain associated with open weights, they could lead to larger open models to exist trailing the frontier. And while it’s unlikely that the small decentralized training projects will amass large frontier amounts of compute, thanks to compute efficiency advances and the increased efficiency of hardware, I expect decentralized training runs to not trail that far behind the frontier.

One practical implication is that decentralized training projects put a limit on the scale of models that can be affected by regulation, at least insofar as enforcing such regulations relies on training happening in large data centers.

Thank you to Arthur Douillard, Max Ryabinin, Eugene Belilovsky, Sami Jaghouar, Fares Obeid, Josh You and Aaron Scher for comments and suggestions. Jaeho Lee and Venkat Somala collected data for the charts. Lynette Bye edited the piece.

As part of the research that went into this piece we investigated over 100 papers related to decentralized training. You can find an annotated database of these papers here.

Notes

-

Managing a heterogeneous, inconsistent network requires important engineering resources, but through clever engineering it is ultimately feasible (see for example the work on SWARM or Tasklets). ↩

-

DeepSeek v3 was trained on 14.8T tokens using a batch size of 63M, for a total of 14.8T / 63M ≈ 235k updates. At 32-bit precision, each update takes 2 x 671B parameters x 32 bits per parameter / 60 Mbps ≈ 8 days, and the whole training would take 235k updates x 8 days / update ≈ 5,000 years. ↩

-

60 Mpbs * 10 minutes / 2 uplink and downlink / 32 bits per parameter ≈ 600M parameters. ↩

-

With a proper streaming schedule, we could train the same model with 38 minutes / 7 minutes ≈ 5x less bandwidth while still completely hiding the communication time behind computation. Naively, this suggests we could train a model with 5x more parameters. However, a larger model would be trained with a larger cluster, shortening the computation time per outer step. The communication time grows linearly with model size. The computation time grows with the batch size and the model size, and decreases with the computational power. The batch size grows with the 0.3 power of the dataset size, which itself grows proportionally to the model size under Chinchilla scaling. And the computational power grows proportionally to the square of model size under Chinchilla scaling. So if we increase the model size by a factor n, the computation time decreases by a factor

\(\frac{n \,(\text{model size}) \cdot n^{0.3} \,(\text{batch size})}{n^{2} \,(\text{cluster throughput})}\)

\(= \frac{n^{1.3}}{n^{2}}\)

\(= \frac{1}{n^{0.7}}\)

and the synchronization time grows by a factor \(n\). The synchronization time can be almost fully masked while its below the computation time, so we can grow the model at the same bandwidth until it is

\(38\ \text{minutes} \times \frac{1}{n^{0.7}}\)

\(= 7\ \text{minutes} \times n\)

Solving for \(n\), this allows for training a model

\(n = \left(\frac{35\ \text{minutes}}{7\ \text{minutes}}\right)^{\frac{1}{1.7}} \approx 2.7\)

times larger. ↩ -

IREN (Iris Energy) — “November 2024 Monthly Investor Update” filed on the SEC’s EDGAR system says: “1 EH/s = $30m cost to deliver” (including mining hardware + infrastructure capex) and lists the assumptions (fleet efficiency 15 J/TH, $18.9/TH ASIC pricing, and $750k/MW infrastructure capex). YCharts shows 942.95 EH/s. Combining both numbers, Bitcoin infra is valued at about $30bn. ↩

-

Google Deepmind and Meta have produced significant research on decentralized training. One key motivation that decentralized training techniques can be adapted to reuse older hardware and address fault tolerance. ↩