AI Chip Sales Documentation

Overview

Epoch’s AI Chip Sales dataset tracks aggregate AI accelerator shipments and total compute capacity across major chip designers and manufacturers.

The data is available on our website as a visualization or table, and is available for download as a CSV file, updated daily. For a quick-start example of loading the data and working with it in your research, see this Google Colab demo notebook.

If you would like to ask any questions about the data, or suggest companies that should be added, feel free to contact us at data@epoch.ai.

Use This Work

Epoch’s data is free to use, distribute, and reproduce provided the source and authors are credited under the Creative Commons Attribution license.

Citation

Josh You, Venkat Somala, Yafah Edelman, ‘Data on AI Chip Sales’. Published online at epoch.ai. Retrieved from: ‘https://epoch.ai/data/ai-chip-sales’ [online resource], accessed BibTeX citation

@misc{EpochAIChipSales2025,

title = {Data on AI Chip Sales},

author = {{Josh You, Venkat Somala, Yafah Edelman}},

year = {2025},

month = {01},

url = {https://epoch.ai/data/ai-chip-sales},

note = {Accessed: }

}}Methodology

Summary

This dataset currently tracks estimates of total sales or shipments of the flagship AI chips designed or sold by Amazon (Trainium/Inferentia), AMD, Huawei, Nvidia, and Google (TPU).

For most chip types and time periods, exact chip sales are not disclosed by the relevant companies, though Nvidia has provided the most informative direct disclosures on total Hopper and Blackwell sales. All of our figures are estimates grounded in data and research, though often with significant uncertainty.

Below, we break down specific methodologies and assumptions for each chip designer. In short:

- For AMD and Nvidia, we use revenue-based models that start from revenue data from earnings disclosures and commentary. We allocate this to different products using earnings commentary, and estimate average selling prices based on media reporting and analyst estimates.

- For Google’s TPU, we estimate Google’s TPU spending based on Broadcom earnings commentary and media reporting, and estimate average price paid per chip using a bill-of-materials production cost model, combined with estimates of Broadcom’s profit margin on TPUs.

- For Amazon, we anchor on estimates of large-scale Trainium data centers, supplemented by estimates and information from analysts.

- For Huawei, we directly synthesize volume estimates from third-party analysts.

Amazon

Amazon has ramped up its deployment of its custom Trainium and Inferentia AI chips in recent years. They launched the latest model, Trainium3, in December 2025, though it is unclear if volume shipments have begun.

In short, Amazon has probably deployed 2-3 million Trainium2 chips by the end of 2025, along with hundreds of thousands of older Trainium1 and Inferentia chips, with Anthropic as the dominant customer. Here, we explain how we estimate these volumes. We focus on 2024-2025 due to lack of evidence about previous years, and presumed low volumes before 2024.

Summary of evidence

Our estimate of Trainium volumes are primarily based on two stylized facts:

- Anthropic is by far the largest user of Amazon Trainium chips, and Amazon/Anthropic have built two frontier-scale data centers totaling an estimated 1.3M Trainium2 chips as of January 2026.

- These Anthropic deployments are a very large chunk, perhaps about 50%, of the total Trainium2 stocks deployed to date.

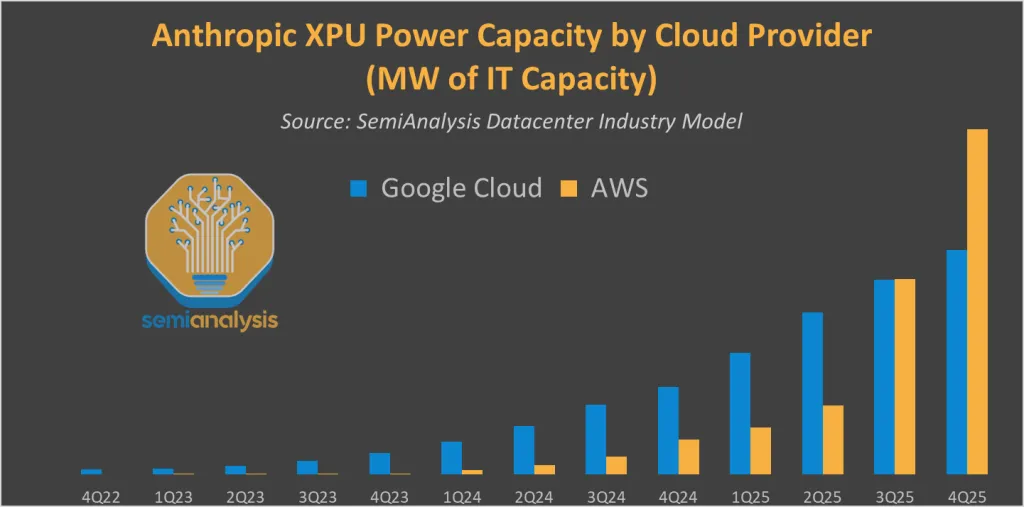

We also have a separate estimate from Omdia of 1.3 million Trainium/Inferentia chips deployed in 2024, without distinguishing between chip types. And SemiAnalysis, an independent semiconductor research firm, has produced estimates of relative Trainium growth over time, though they don’t publicly disclose their estimates of absolute Trainium volumes.

Evidence from Anthropic Amazon data centers

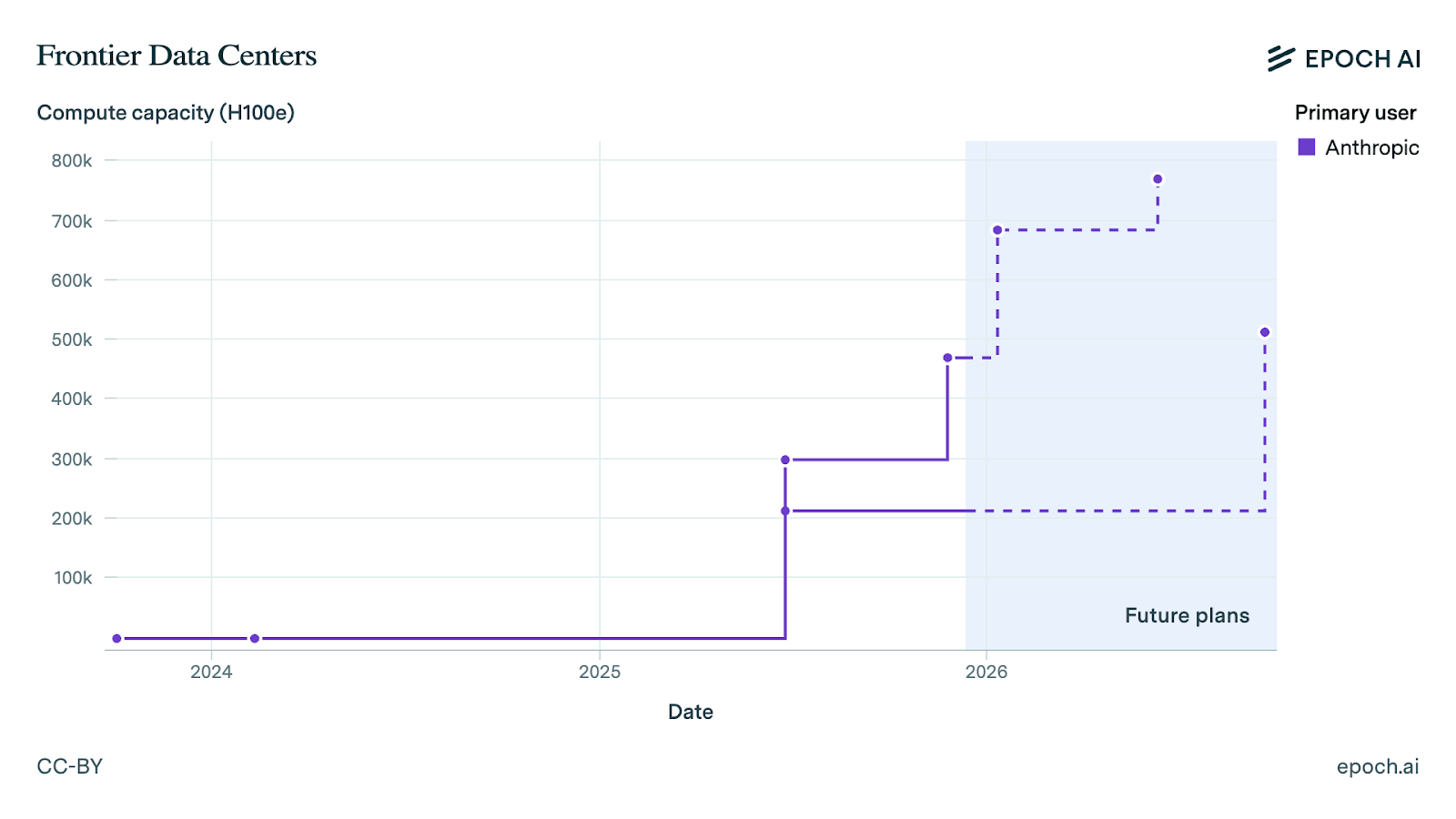

Epoch’s Frontier AI Data Centers dataset tracks the scale of two large operational Amazon–Anthropic data centers, both part of “Project Rainier”. These numbers come from a mix of analysis of satellite data and statements from Amazon. The larger one is located in New Carlisle, Indiana, and the other in Canton/Madison Mississippi. Both data centers probably exclusively use Trainium2, though this is only confirmed for New Carlisle.

As of June 2025, New Carlisle and Canton together were already at 750k Trainium2 units. By January 9, 2026, New Carlisle will have 1M Trainium2 online (corroborated by Amazon’s claim of 1M online by end of 2025), for a total of ~1.3 million Trainium2 between the two campuses. While it is not confirmed as of writing (January 7) that 1M Trainium2 are actually operational in New Carlisle, Amazon very likely has procured this many chips intended for that data center, given that there is a time delay between acquiring chips and installing them in a data center. This could also be an underestimate for Canton because of the lumpiness of updates, as the estimate for Canton dates to June 2025.

Note: the y-axis of this graph is in H100e. 1 H100e ~= 1.5 Trainium2.

Inferring total Trainium volumes from Anthropic data centers

Given that Amazon and Anthropic have deployed ~1.3 million Trainium2 in two large data center campuses, New Carlisle and Canton, what sort of bounds can we place on the total stock of Trainium?

Lower-bounding the total stock

According to SemiAnalysis (as well as common sense), New Carlisle and Canton don’t contain all of Anthropic’s Trainium chips, much less all Trainium(2) in the world. They estimate Anthropic’s Trainium capacity in Q1, which predates these two campuses, was roughly 15% of its Q4 2025 capacity.

We also know, from research firm Omdia, that Amazon deployed over 1 million of its custom AI chips in 2024, predating these two data centers. These may have been mostly older Trainium1 and Inferentia chips that are around 25% as powerful as Trainium2, but this would still be the equivalent of >200k Trainium2. And Amazon was using 80,000 Trainium 1 chips to run a single product (Rufus, the chatbot on Amazon.com) in summer 2024.

Upper-bounding the stock

These Anthropic data centers are probably a large share of total Trainium volumes:

- Amazon Q3 2025 earnings reported that Trainium2 revenue (meaning cloud revenue from renting out Trainium) “grew 150% quarter over quarter”, coinciding with Project Rainier coming online around June 2025. This suggests that these two campuses are over half of the Trainium cloud fleet. Since New Carlisle doubled in H2 2025, Rainier’s share may have grown further since Q3.

- SemiAnalysis claims that Anthropic is the only large external Trainium2 user, and “materially larger than Amazon’s internal needs” for services like Bedrock and Alexa. This suggests that including Amazon’s internal Trainium fleet doesn’t dramatically change the picture.

- Supply chain estimates suggest an upper bound on production. Morgan Stanley,, used TSMC CoWoS wafer allocations to estimate in early 2025 that 1.1-1.4 million Trainium2 would be produced in 2025.1 This now looks like an underestimate, but does suggest that 2025 Trainium2 shipments are unlikely to be far greater than Rainier’s 1.3M total.

Overall, it looks like the 1.3M Project Rainier chips are a large chunk of total Trainium2. This makes much higher volumes (e.g. 4M or more Trainium2) less likely. As a result, we use 2M to 3M Trainium2 as a plausible range of the Trainium2 stock, with 2.5M as a point estimate (implying that New Carlisle and Canton together are about half of the total deployed stock).

Estimating volumes and deployment timelines

Starting from a point estimate of 2.5M Trainium2 deployed as of end of 2025, how much total Trainium (including older models) were shipped/deployed over time?

- As noted above, Omdia estimates 1.3 million Trainium and Inferentia chips deployed in 2024, without breaking this down by chip type. Trainium2 became available in late 2024, so this production was split between Trainium2 and earlier generations.

- Anthropic’s Project Rainier data centers ramped heavily in mid-late 2025. At the end of H1 2025, New Carlisle and Canton were already at a combined 750k Trainium2.

- SemiAnalysis estimated relative growth of Trainium package production over time. Their chart shows that Trainium2 production increased by ~4x between 2024 and 2025, implying that 2024 Trn2 production was ~20% (~500k) of the cumulative total, though they note there is a time delay between package production and server shipments.2

- They also show 6x growth over two years (or 25% growth per quarter). In 2025, this quarterly growth rate slowed to 12%. If 2M Trainium2 were shipped in 2025, this growth range implies 780k to 890k were shipped in H1 2025.3 The higher end looks more plausible given Project Rainier already reaching 750k by mid-year.

Overall, we have this timeline of rough estimates:

- 2024: 500k-1M Trainium1/Inferentia, and ~500k Trainium2

- 2025 H1: ~850k Trainium2

- 2025 H2: ~1.15M Trainium2

Cost per chip

There is limited media and analyst coverage of Trainium costs, though SemiAnalysis estimates Trainium2 at a ~$4k unit cost per chip for Amazon.

This is much lower than competitors like the Nvidia H100 (priced at >20k each), despite Trainium2 having ~66% the FLOP/s spec of an H100 and a similar amount of memory. But this figure is plausible because Amazon’s custom chip effort is heavily vertically integrated, Amazon having acquired the chip designer Annapurna Labs. The Nvidia B200, which is more complex and has 2x more memory than Trainium2, likely only costs around $6k to produce. Amazon still partners with external chip design firms Marvell and Alchip, but this is reportedly much less lucrative for them than (e.g.) Google’s TPU is for Broadcom.4

Huawei

Huawei’s Ascend 910-series chips are China’s leading domestically-designed AI accelerators, with the 910B and 910C being the primary models in recent years. Huawei Ascend volumes are covered fairly extensively by other analysts, so we primarily summarize and synthesize this external work. We focus on 2024 and 2025, as there is less coverage of previous years, and it is likely that the vast majority of Huawei Ascends are less than two years old.

2024 Production

For the Ascend 910B, analysts largely agree on 400,000–450,000 units. 36kr reported roughly 400,000 shipments, while both SemiAnalysis and Bernstein came in at 450,000. The Financial Times was a notable outlier at just 200,000. For the newer 910C, only SemiAnalysis provided an estimate: around 50,000 units in limited initial production.

2024 totals: ~400k 910B and ~50k 910C

2025 Production

Estimates diverge more for 2025, especially on the 910B/910C mix. SemiAnalysis projects 152,000 910Bs and 653,000 910Cs—a significant shift toward the newer chip. Bernstein sees a more even split at 350,000 of each. Bloomberg reported ~300,000 910Cs for 2025, with plans to double that in 2026.

The U.S. Commerce Department offered a much lower figure—just 200,000 total Ascends. This number is out of step with other estimates and may be scoped to chips produced entirely in China’s indigenous supply chain. Until the relevant export controls were tightened recently, Huawei relied on imports from TSMC to acquire logic dies for Ascends, as well as HBM imports.

For our 910C estimate, we have greater confidence in SemiAnalysis’s higher figure of ~600,000, due to its far greater detail (the other analyst estimates are simply reported in the media) and SemiAnalysis’ relative expertise in semiconductors.

2025 totals (best estimate): ~200k 910B and ~600k 910C

Estimating the compute-equivalent total of Huawei Ascends

Given these estimates of Ascend volumes, what is the total computing power of the Ascend stock? The challenge is that there are multiple published specs for both the 910B and 910C. The 910B is commonly quoted at 320 16-bit TFLOP/s, but subvariant specs range from 280 to 400 TFLOP/s. Similarly, the 910C is most often quoted at 800 TFLOP/s (possibly rounded), though SemiAnalysis claims 780 TFLOP/s.

To handle this uncertainty, we use a Monte Carlo model, with a range of 280 to 400 TFLOP/s for the 910B and 780 to 800 TFLOP/s for the 910C. In addition, for the purpose of this dataset, we use the maximum OP/s rating for 8-bit (or greater) number formats. For the 910B, INT8 specs are 2x higher, or 560 to 800 TOP/s. While published INT8 specs are not available for the 910C, we assume the 910C’s maximum INT8 output is approximately 2x higher than its FP-16 rating, at ~1500 to 1600 TOP/s.

We also apply uncertainty intervals for unit counts based on the research above.

This model yields 180K H100-equivalents in 2024 (90% credence interval: 130K–240K), of which 140k comes from 910Bs and 40k from 910C, and 530K H100-equivalents in 2025 (450K–620K), split between 70k 910B and 460k 910C.

AMD

AMD sells AI chips called Instinct GPUs. They are arguably the largest competitor to Nvidia in selling AI chips that are not custom-designed for specific companies/applications (such as Google/Broadcom’s TPU and Amazon’s Trainium).5

We estimate AMD’s AI chip sales6 by first:

- Estimating AMD’s total revenue from Instinct GPU sales.

- Estimating average selling prices for each GPU model based on media reports and analyst coverage.

- Modeling the production mix across different GPU generations each quarter based on product launch dates, known customer deployments, and company commentary.

With quarterly Instinct revenue, GPU pricing, and production mix estimates, we can calculate unit volumes by dividing revenue by weighted-average prices. We implement this using Monte Carlo simulation to model uncertainty from all input parameters and report results as median values with confidence intervals. The full model can be found here.

How much revenue does AMD make from AI GPUs?

AMD reports its “data center” revenue each quarter (as in, revenue from its division that sells products intended for data centers), but they do not break out how much revenue comes from Instinct AI GPUs versus other products like its EPYC CPUs. To estimate Instinct revenue, we rely on company disclosures and work backwards from a few anchor points.

The most important anchor is AMD’s disclosure that Instinct revenue exceeded $5 billion in 2024. A secondary anchor helps us distribute this $5B across quarters in 2024. In AMD’s Q2 2024 earnings call, Lisa Su, AMD’s CEO, noted that Instinct MI300 revenue exceeded $1 billion for the first time. This helps ground how we model the quarterly distribution of the $5+ billion for 2024.

For 2025, we are less certain about Instinct GPU revenue.

AMD’s data center segment grew overall in 2025, but experienced headwinds in Q1 and Q2 2025 from two factors. First, new U.S. export controls in April 2025 restricted AMD’s MI308 chips designed for the Chinese market, resulting in an $800M charge in Q2. Second, AMD faced unexpectedly weak demand for its new MI325X GPU. We estimate that Instinct’s share of datacenter revenue fell from ~50% in Q4 2024 to ~40% in Q1 2025 and ~30% in Q2 2025.

This decline reversed in Q3 2025 when AMD introduced a new GPU generation, the MI350 series, which “ramped really nicely” and drove Q3 growth. We estimate Instinct represented 35-50% of Q3 2025’s $4.34B datacenter revenue, or ~$1.5-2.3B in revenue.

We have meaningful uncertainty because AMD does not regularly disclose the EPYC/Instinct split. The actual revenue distribution could differ, particularly in quarters where we have limited direct information.

| Quarter | DC Revenue | Instinct Share | Instinct Revenue | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 2024 | $2.34B | ~30% | ~$0.7B | Assumption based on ramp trajectory |

| Q2 2024 | $2.83B | ~36% | >$1B | Company disclosure |

| Q3 2024 | $3.55B | ~42% | ~$1.5B | Interpolation |

| Q4 2024 | $3.86B | ~47% | ~$1.8B | Interpolation |

| 2024 Total | $12.6B | 44% | ~$5B | AMD FY2024 |

| Q1 2025 | $3.67B | 35-45% | $1.3-1.7B | MI308 export controls, MI325X weak demand |

| Q2 2025 | $3.24B | 25-40% | $0.8-1.3B | $800M MI308 charge, continued softness |

| Q3 2025 | $4.34B | 40-53% | $1.7-2.4B | MI350 ramp |

Average Selling Price

In order to convert Instinct revenue into unit volumes, we need to estimate what AMD sells each Instinct GPU for. Our estimates primarily draw from industry analyst reports.

We model each ASP as a uniform distribution within ranges anchored on media reports and analyst estimates.

| GPU Model | Price Range | Source |

|---|---|---|

| MI250X | $8,000-12,000 | Massed Compute |

| MI300A | $6000 - $7500 | Derived from El Capitan cost / # of units |

| MI300X | $10,000-15,000 | Tom’s Hardware; Citi via SeekingAlpha (Microsoft pays ~$10k) |

| MI325X | $10,000-20,000 | Low end reflects hyperscaler discounts amid soft demand |

| MI350X | $22,000-25,000 | Seeking Alpha (reports of $25k pricing) |

| MI355X | $25,000-30,000 | Seeking Alpha |

GPU Revenue Mix Over Time

Estimating the quarterly split between GPU models is necessary to measure the total compute capacity of AMD chips because GPUs vary in cost-effectiveness.

We model the revenue mix using product launch timelines, known customer deployments, and company commentary about production ramps. We estimated most 2024 sales came from the MI300 series, with a small share for the legacy MI250X, MI300A, and MI300X. In Q3 2025, the next-gen MI350 series launched ahead of schedule and we estimate that it quickly captured the majority of Instinct revenue. A more detailed timeline is shown below, with the full parameters available in our model.

We have significant uncertainty about the revenue mix because AMD does not disclose precise product shares. The actual mix could differ substantially, particularly during product transition periods when multiple generations overlap.

| GPU | Release date | Description | Revenue share notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MI250X | Nov 2021 | Previous-gen flagship GPU | Legacy product with minor share in early 2024 |

| MI300A | Jan 2023 | First 300 series, designed for HPC over AI | Most of the 44.5K MI300A for El Capitan were delivered in Q2 and Q3 2024. Ramped down after |

| MI300X | Dec 2023 | Flagship AI GPU, competing with Nvidia H100 | Ramped through 2024, phasing out in 2025 for MI325X |

| MI308X | Dec 2023 | China-spec 300X to meet export controls | Unclear if high-volume shipments ever took place, exports definitively blocked in April 2025 |

| MI325X | Oct 2024 | 300X refresh with more memory, akin to Nvidia H200 | Shipped Q2 2025 at 5-20% share in Q1 2025, grew to 15-40% by Q2 2025 despite soft demand; timing vs B200 hurt |

| MI350 | Jun 2025 | Next-gen GPU, competing with Nvidia Blackwell | Volume production ahead of schedule; primary driver of Q3 2025 growth |

Volume Calculation

With quarterly Instinct revenue estimates, ASP distributions for each model, and production mix shares, we calculate unit volumes by multiplying total GPU revenue by each model’s production share to get model-specific revenue, then dividing by that model’s ASP.

Rather than working with point estimates, we sample from all the probability distributions simultaneously and compute the resulting unit volumes using Monte Carlo simulations.

Limitations

Our analysis has several sources of uncertainty that create several limitations:

Revenue allocation - AMD doesn’t report the EPYC/Instinct split for most quarters. We anchor on disclosed data points but if AMD’s actual EPYC/Instinct mix differs from our estimates, either because EPYC grew faster or slower than we assumed, our GPU revenue estimates would be biased.

Production mix - We estimate GPU model shares from product timelines and deployment reports, but AMD doesn’t disclose actual splits. The actual splits could differ substantially from our estimates, especially during product transitions. This matters because different models have different prices and misestimating the mix between a $15,000 and $25,000 GPU directly affects unit counts.

Pricing - GPU pricing varies by customer, contract structure, and timing in ways our ASP ranges would not fully capture. Large bulk purchases as well as customer demand can meaningfully affect average per-GPU prices. We model ASPs as uniform distributions within reported ranges, but actual contract prices likely have more complex distributions.

MI308 export controls on Q2 2025 and subsequent quarters remains uncertain. AMD disclosed the $800M Q2 charge and $1.5-1.8B annual impact, but the full effect on product mix, pricing, and customer allocation is difficult to model precisely.

Deployment lag - Our estimates reflect chips produced and sold by AMD, not necessarily chips deployed and operational in customer data centers. There may be deployment lags between when AMD recognizes revenue and when chips are online. For quarterly analysis, these timing differences could shift volumes between periods.

Summary

AMD’s Instinct GPUs compete with Nvidia’s data center accelerators but represent a much smaller share of the AI compute market. We estimate Instinct GPU volumes in 2024 and 2025 to understand AMD’s position in the AI chip market.

AMD bundles its Instinct GPU revenue with EPYC server CPU revenue in a single data center segment. This makes it more difficult to track AMD’s revenue from their Instinct GPU line. We estimate unit volumes by inferring GPU revenue and dividing by average chip prices. The main revenue anchor point is AMD’s statement that 2024 Instinct revenue exceeded $5 billion. We also use their Q2 2024 disclosure that MI300 revenue surpassed $1 billion that quarter. These two points let us estimate how GPU revenue was distributed across other quarters, accounting for product launches, media reports on adoption, and production schedules AMD discussed in earnings calls.

We estimate prices for each GPU model from analyst reports and media coverage of customer contracts. Hyperscalers like Microsoft pay around $10,000 per MI300X in volume, while newer models like the MI350X sell for $22,000-25,000. Production mix across GPU generations comes from product timelines, known deployments, and company statements about manufacturing. We run Monte Carlo simulations to propagate uncertainty rather than using point estimates.

Overview

Google designs custom AI accelerators called Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), which are used by Google DeepMind for training and inference, by Google at large for AI/machine learning tasks, and by external cloud customers such as Anthropic.7

Google partners with Broadcom, a major chip designer, to produce the TPU. Google designs the high-level TPU architecture, while Broadcom handles physical design and supply logistics, including placing manufacturing orders with TSMC. In short, Google buys TPUs from Broadcom, which oversees their production.

Google does not disclose its TPU volumes, but we have a significant amount of evidence we can use to estimate these volumes. We use the following methodology:

- We estimate how much Google spends on TPUs using Broadcom statements about their revenue from AI chips and AI hardware, and reports and estimates of Google’s share of that revenue.

- We then figure out the average price of TPUs: First, we use a bottom-up model to estimate what TPUs cost to produce (i.e. how much they cost for Broadcom). We then adjust this using reports/statements about Broadcom’s gross margins on TPUs to estimate how much Google pays per TPU.

We focus on 2024-2025 sales for now because there is more information available on total TPU spending.

Given that many inputs are uncertain, we use Monte Carlo simulations and report results with confidence intervals. The full model can be found here.

TPU Spend

Broadcom reports AI semiconductor revenue each quarter, but this includes both custom AI accelerators (so-called XPUs, which includes TPUs) and networking products. However, on earnings calls, Broadcom’s leadership has said that XPUs account for roughly 65 - 70% of its AI semiconductor revenue, which allows us to isolate XPU revenue. For example, Broadcom’s FY2024 AI semiconductor revenue was $12.2B, implying $8 - 8.5B in XPU revenue.

Note that Broadcom’s fiscal quarters run about two months ahead of the calendar: for example, their Q4 2025 ended on November 2. When visualizing our results by quarter, we use interpolation to distribute TPU counts by calendar quarter.

The next step is estimating Google’s share of that XPU revenue:

In 2024, Broadcom’s two primary XPU customers were Google and Meta. Meta reported spending approximately $987M with Broadcom in 2024.8 Subtracting disclosed customer spending from total XPU revenue implies that Google’s TPU-related spend with Broadcom in 2024 was roughly $7 - 7.5B.

In 2025, Broadcom had almost exactly $20B in AI semiconductor revenue in 2025. They said XPUs were a 65% share of AI semis in Q3 2025, similar to 2024, so the full year share was likely similar as well, for around $13B in XPU revenue.

We can estimate Google’s TPU/XPU spend a few ways:

- Google increased its capital expenditures from $52B in 2024 to $91B-93B in 2025, a roughly 75% increase. Google’s capex and capex growth is predominantly due to AI spending, though they do not consistently break out AI capex. If Google’s Broadcom spend scaled similarly from ~7-7.5B in 2024, this suggests $12-13B in TPU-related spend.9

- Extrapolate estimates that Google accounts for ~90% of Broadcom XPU revenue in 2025, implying roughly $12B in spending. HSBC estimated that Google will make up 78% of Broadcom ASIC revenue for 2026, which suggests that TPU share of Broadcom ASIC revenue in 2025 could be 85%+ since Broadcom will be scaling additional XPU programs with other designers in 2026.

- Validating against other analyst estimates, which model Broadcom XPU revenue from Google to be between $11-13B.

TPU Price Modeling

From the previous step, we have an estimate of how much Google spent on TPUs with Broadcom. To translate this spending into TPU production volumes, we divide estimated revenue by per-chip prices. This has two steps:

- Estimate the production cost to Broadcom for each TPU generation using a bill of materials model

- Estimate the price Google pays, given reports of Broadcom’s margins

Bill of materials cost model

The cost of manufacturing a TPU can be broken down into four components.

- Logic die cost is estimated from publicly reported wafer prices at each process node and die size estimates from industry analysts, adjusted for yield assumptions that vary with die size and process node.

- HBM cost is based on reports of memory pricing by generation and the memory capacity.

- Advanced packaging cost covers TSMC’s CoWoS process, estimated from their advanced packaging revenue disclosures and capacity allocation reports.

- Auxiliary costs include the power delivery hardware, PCB, and module-level assembly and testing.

Our estimates draw from publicly available information including wafer pricing, memory costs by generation, and packaging costs derived from TSMC’s capacity and revenue disclosures. The estimates vary by TPU generation, since newer chips use more advanced processes, larger dies, and more memory.

Broadcom margins

Broadcom may make around a 60% gross profit margin on TPUs, with a plausible range of 50% to 65%:

- In Q1 2024, CEO Hock Tan said that the custom chip business “can command margins similar to our corporate gross margin.” which was around 75% at the time.

- For FY2023, we estimate margins between 55-70%, reflecting higher margins earlier in the Google-Broadcom partnership..

- In earnings calls in 2025, Broadcom consistently said that XPU margins were lower than for their overall business (which was mid-high 70s), and also hinted that XPU margins were lower than their overall semiconductors segment (mid-high 60s).10

- One analyst, UBS, estimated a 55% margin on XPUs.

A 60% margin would mean that a chip that costs Broadcom $1k to produce would then sell for $1k / (1 - 60%) = $2,500.

Summary of results

| TPU Version11 | Manufacturing Cost | Price to Google | Median Price to Google |

|---|---|---|---|

| v4i | $700 - $1100 | $1700 - $3200 | $2,300 |

| v4 | $1100 - $1500 | $2700 - $4500 | $3,400 |

| v5e | $950 - $1400 | $2000 - $3500 | $2700 |

| v5p | $2300 - $2900 | $5000 - $7600 | $6000 |

| v6e | $1600 - $1900 | $3400 - $5000 | $4100 |

| v7 | $4600 - $5500 | $9800 - $14700 | $12000 |

Our cost estimates cover the TPU module only and exclude networking. While networking is a meaningful system-level cost, Broadcom counts it separately from its XPU revenue. We therefore exclude networking to ensure consistency between the revenue data and the cost model.

Our estimates are generally aligned with external reports. One semiconductor research firm estimated prices of $3k for the v5e, $6k for the v5p, and $4k for the v6e, all of which align closely with our median estimates. However, the same source estimated the v7 (formerly v6p) at $8k, significantly lower than our $12k median. Other reporting places the v7 higher: one analyst estimated $13k, while The Information reported $12k. These latter estimates align well with our own.

Production Mix

To convert total TPU revenue into chip counts by generation, we estimate the quarterly production mix across TPU versions over time. The production mix matters because TPU generations differ substantially in cost. Inference-optimized chips are cheaper than training-focused chips with larger memory footprints, and newer generations are more expensive than older ones due to advanced process nodes and packaging. We model the quarterly production mix as probability distributions across TPU versions, with shares normalized to sum to 100%.

Our production mix estimates are informed by discussions with experts as well as industry reporting. Several key insights shape our modeling approach:

First, our understanding is that TPU production ramps are much shorter than (e.g.) Nvidia or AMD GPU ramps. Unlike GPU production, which typically involves gradual multi-quarter transitions with significant overlap between generations, TPU production tends to follow a ‘one chip at a time’ pattern. Production switches relatively quickly from one generation to the next, with minimal overlap. For example, when v5e production ended and v6e began in Q4 2024, there was no extended period of parallel production. Rather, the line switched from making one chip to the other.

One nuance to the above is that inference-optimized chips (v4i, v4, v5e, v6e) and training-focused chips (v5p, v7) tend to be produced in parallel. Within each of these two classes of chips, production from one generation to the next rather than running multiple generations in parallel.

Next, TPU models ramp into production before or around the time that Google makes a “preview” announcement, and are already in full production by the time Google announces that they are “generally available”. SemiAnalysis noted that “Google started announcing TPUs as they ramp into production rather than after the next generation was being deployed.” This means production often begins before or around the time of public preview announcements, and scales quickly to general availability. For example, for TPUv5e, meaningful production volumes began several months before the August 2023 GCP preview announcement.

Here is a summary table and plot describing when each TPU reached general availability. The full parameters can be found in our model.

| TPU Model | Preview availability date12 | Description | Production mix notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| v4i | Q1 2020 | Inference only chip | Included as a small share in Q4 2022 production before transitioning to v4. |

| v4 | May 2022 | Efficient and scalable chip. | Primary production in Q1 - Q2 FY23, declining rapidly in Q3 FY23 as v5e ramps. Production ends by Q3 FY23. |

| v5e | August 2023 | Small, cost-optimized inference chip. | Production begins earlier than v5e Google Cloud preview date, with meaningful volume starting Q2 FY23. Becomes dominant by Q3-Q4 FY23 as the production line quickly switches from v4 to v5e. Production ends as v6e ramps in Q4 FY24 |

| v5p | Dec 2023 | Training-focused chip. | Ramps alongside v5e starting Q1 FY24. Since the v5p is a high-performance training-focused chip with significantly more memory than the v6e, it may remain better suited for certain workloads even after v6e reaches full volume. We assume v5p production continues at relatively constant levels through FY25 before transitioning to v7. |

| v6e | Oct 2024 | Next-gen cost-optimized chip | Appears in pilot volumes in late 2024. We model full production volume of v6e starting in Q4 2024 and continued volume in 2025. Minimal overlap with v5e production given the production line switches from one to the other. |

| v7 | Nov 2025 | Powerful next-gen chip | Enters production in H2 2025. Contributes a minority but meaningful share in Q3 2025, with large-scale ramp deferred to 2026. |

Volume Estimates

Chip volumes are calculated by dividing quarterly TPU revenue by the weighted-average price per chip. We implement this using Monte Carlo simulations to propagate uncertainty from all input parameters including revenue estimates, production mix shares, manufacturing costs, margins, and more. Results are reported as median values with 90% confidence intervals.

Limitations

This analysis relies on indirect estimation from proxies, which introduces uncertainty in a few areas:

- Customer allocation: Broadcom’s XPU revenue is divided among multiple customers, and the exact split between customers is not disclosed. Our estimates rely on limited data points that may not fully represent the competitive dynamics.

- Contract-specific pricing: Component prices are negotiated individually and can vary significantly by volume and customer relationship. The prices Google pays may differ from the rates reported by second-hand sources we use in our cost model.

- Production versus deployment: Our estimates reflect chips manufactured by Broadcom, not chips deployed and operational in Google data centers. There may be lags between production and deployment that our model cannot capture.

- TPU version mix uncertainty: There is little information from Google and media reports on production mix by TPU version. Our production split estimates between TPU versions relies heavily on conversations with TPU experts and analysts. The actual mix could differ substantially, which affects volume estimates since different generations have very different prices. While we are directionally confident in our estimates, the individual estimates have significant uncertainty.

Summary

This model estimates Google’s TPU production volumes by combining Broadcom’s publicly disclosed AI semiconductor revenue with bottom-up cost estimates for each TPU generation. We isolate custom accelerator revenue from Broadcom’s reported totals, estimate Google’s share, model per-chip manufacturing costs, and infer the quarterly production mix from product timelines and industry reporting. Dividing estimated spending by weighted-average prices gives us chip production volumes.

There are several sources of uncertainty including the allocation of Broadcom revenue between customers, contract-specific pricing, and the production mix between TPU generations. Results are reported as median values from Monte Carlo simulations with confidence intervals reflecting these uncertainties.

Nvidia

Nvidia is the largest seller of AI chips, which they call “GPUs”. Here, we explain how we estimated total Nvidia AI GPU shipments from 2022 onwards. We focus on Nvidia’s flagship AI GPUs, not its gaming GPUs (which are used by some AI practitioners) or chips for self-driving cars.

We estimate Nvidia AI GPU sales based on Nvidia’s revenue from AI compute, and reported/estimated prices of its GPUs over time, as well as announcements and Nvidia statements of which chip types were shipped over time.

We then compare the results of this model from a public disclosure from Nvidia that it has shipped 4M Hopper GPUs and 3M Blackwell GPUs through October 2025.

Revenue-based model

The code for this model can be found here.

The revenue-based model uses this approach:

- We find Nvidia’s revenue from AI compute (AI GPUs/servers) over time, which Nvidia reports every quarter. This data runs through October 2025, the most recent quarter.

- For each quarter, we record or estimate how Nvidia’s compute revenue breaks down by GPU model (e.g. A100, H100), mostly based on Nvidia’s earnings commentary.

- Then, we estimate the number of GPU units shipped using reports and estimates of the prices of GPUs and other equipment.

We restrict our data to 2022, which should capture a very large majority of the existing stock of Nvidia chips, given a typical lifespan that is likely between 3-6 years13 and rapid growth in sales over time.

Nvidia’s AI GPU revenue

Nvidia breaks out revenue for its “Data Center” division, which sells products intended for data centers. Data Center has been >80% of Nvidia’s total revenue since 2024 and includes all of Nvidia’s mainstream AI chips, but not gaming GPUs and its self-driving car chips (which are out of scope for our counts).

Nvidia breaks down “Data Center” further into Compute and Networking, with Compute making up 80-85% of Data Center in recent years.14 Networking means cables, switches, and other components used to connect chips together. This is vitally important for creating chip clusters, but we mostly ignore networking revenue for the purpose of estimating chip counts.

A small nuance is that “Compute” is more than physical compute sales. Nvidia describes (page 5) its Compute sales as including hardware (GPUs, CPUs, and interconnects), cloud compute revenue (DGX Cloud), and AI-related software products.15 Software and cloud are likely a very small share; for example, they were $2 billion in revenue in 2024, compared to ~$100B in total Compute revenue. We assume that ~95-99% of Compute revenue is from hardware sales. Additionally, Nvidia’s cloud division mostly uses compute that Nvidia sells and then rents back.16

This revenue data is summarized below. Note that Nvidia’s fiscal year ends in January and runs ~11 months ahead of the calendar year (e.g. FY25 ended January 26, 2025). Because their quarters do not line up with calendar quarters, in our visualizations we use interpolation to distribute GPU counts by calendar quarter.

| Period | Data center revenue | Compute revenue |

|---|---|---|

| Fiscal year 2023 (approx. Feb 2022 - Jan 2023) | $15.0B | $11.3B |

| Fiscal year 2024 (Feb 2023 - Jan 2024) | $47.5B | $38.9B |

| Fiscal year 2025 (Feb 2024 - Jan 2025) | $115.3B | $102.3B |

| FY 2026, first three quarters (Feb 2025 - Oct 2025) | $131.4B | $111.0B |

Nvidia’s revenue mix over time

Given total revenue and prices of chips over time, the next step is allocating quarterly revenue to chip type. Nvidia doesn’t consistently break down sales by chip, but they provide substantial details in earnings commentary.

Nvidia’s Hopper generation (H100) launched in late 2022 and ramped massively in 2023 while A100s ramped down. The next major generation, Blackwell, ramped in early to mid-2025. And Nvidia’s China-spec chips made up around 15% of sales while their export was legal (late 2022 to October 2023, and ~Feb 2024 to April 2025; the H200 will also be sold in China in 2026).

An abbreviated timeline with notes is provided below, and more detailed estimates and notes can be found in this sheet.

Note is that we round down the sale of data center GPUs that don’t appear in this list to zero. The main GPU this applies to is the lower-grade L40, released early 2023. There is little information available about L40 sales, but they may have made up a small portion of 2023-2024 sales. We also bucket some GPUs together, like H200s with H100s and B100s with B200s.

| GPU | First shipped | Approx. revenue share | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A100 | June 2020 | Dominant through late 2022 | Flagship pre-Hopper. By September 2023, A100 revenue was “declining sequentially” and at the “tail end” of the architecture. |

| H100 and H200 “Hopper” (bucketed with 2024’s H200 due to lack of breakout and similar specs) | Late 2022 | ~80% of 2023-2024 ~15-20% in first half of 2025 | Flagship AI chip of the post-ChatGPT era. Started shipping by October 2022, and H100 revenue was “much higher than A100” by January 2023. Hoppers were still sold through late 2025. By April, transition to Blackwell was “nearly complete” with Blackwell at ~70%, but the following quarter H100/H200 sales actually increased. |

| A800 | Oct 2022 | A800 and H800 ~20% through late 2023 | China-compliant A100 variant; banned Oct 2023. |

| H800 | Late 2022 | China-compliant H100 variant, banned Oct 2023. China was 19% of data center sales during relevant period. | |

| H20 | Feb 2024 | ~13% from Feb 2024 to April 2025 | Heavily-downgraded Hopper variant for China; eventually banned April 2025. China was about 13% of 2024 revenue, and H20 had $4.6B in sales in spring 2025, or ~13% of compute sales. |

| “Blackwell” B200 (bucketed with B100) | Late 2024 | Majority by mid-2025 | Next generation after Hopper. We bucket B200 bucket with the less powerful B100 due to lack of breakout, and presumed low B100 share. Most B200s are sold in GB200 systems (see notes on B200/B300 below). Quarter ending Jan 2025 had $11B of Blackwell revenue or ~33% share of data center. Next quarter, Blackwell was “nearly 70%” of data center compute. |

| B300 (aka Blackwell Ultra) | Mid 2025 | Majority by late 2025, displacing B200 | Mid-cycle refresh of B200 with “tens of billions” in sales by July 2025, perhaps roughly half of Blackwell. The next quarter it reached two-thirds of Blackwell. |

Chip prices

Note on servers vs chips

To estimate how many GPUs Nvidia shipped, the next step is to divide their Compute revenue by average prices per chip, which we collect using reports and estimates from the media and analysts.

As mentioned above, their compute revenue includes a small amount of software and cloud revenue. Another potentially significant nuance is that Nvidia sells some GPUs bundled into complete servers, which means Nvidia’s Compute revenue captures revenue from non-chip, non-networking server components as well.17 This would increase the effective Compute revenue that Nvidia makes per AI chip.

For context, most Nvidia AI chips are deployed in servers, which are necessary for training and commercial-scale inference, rather than individual cards. Most of the cost of a server is the GPUs themselves, but server components add costs: one bill-of-materials estimate of an 8-GPU H100 server has the full server sold at a ~38% premium vs the 8 GPUs, including networking components. And as we note below, Blackwell NVL72 systems command a broadly similar premium vs individual Blackwell GPUs, with a roughly 40k to 50k server price per GPU for GB200 NVL72 vs 30-40k for standalone B200s.

However, Nvidia’s overall “server premium” is probably much lower than ~30%:

- Most Nvidia servers appear not to be purchased from Nvidia fully-assembled. One 2023 article estimates that Nvidia-packaged H100 servers were 20% of Nvidia data center revenues, meaning non-GPU server components made up <10% of Nvidia’s data center revenue.18 The remainder would be assembled or sold by other companies such as Dell and Supermicro.

- Second, some of these server components would count towards Networking revenue, not Compute.

Overall, a detailed analysis of the Nvidia server market is outside our scope here. We choose uncertainty intervals about chip prices wide enough to incorporate this uncertainty about the server premium.

A100

Standalone A100s cost around $10k in 2023 per CNBC, while SemiAnalysis described it as “$10k+”. A DGX A100 server had a launch MSRP of $199k in 2020 or $25k per GPU (maybe the last Nvidia flagship AI product to have an MSRP), though this includes a server premium, and is before bulk discounts.

For A800s specifically, Financial Times reports a price of ~$10k each in 2023. This is probably a standalone chip price.

Overall, we use an uncertainty interval of $10k to $15k for A100s in 2022-2023, given that reports generally give a lower end of 10k, and a possible server premium.

H100

The Hopper generation has perhaps the best direct evidence of average price, thanks to a disclosure from CEO Jensen Huang himself: Nvidia made a total of $100B in revenue from selling 4 million Hopper GPUs through October 2025 (excluding China). That works out to $25k per GPU on average—though both figures appear to be round numbers, suggesting some rounding.

Other reports include:

- CNBC wrote in March 2024 that analysts generally estimate that H100s cost between 25k and 40k (without distinguishing GPUs vs servers, or whether these price figures are an industry average).

- The Financial Times quoted SemiAnalysis in September 2024, claiming that Nvidia sold H100s for $20k to 23k, after recently cutting prices.

- In May 2023, SemiAnalysis estimated the 8 GPUs in an HGX H100 server sold by Nvidia cost $195k, or $24k per GPU, while the whole server cost ~34k per GPU. We couldn’t find any corroborating reports of H100s being sold for 24k in mid-2023, so it is unclear if this price was actually available to any customer not buying the HGX bundle.

- In 2024, they listed $24k as the average selling price of both the H100 and H200 GPU; an identical price for the upgraded H200 suggests some rounding.

- By 2025, SemiAnalysis updated their estimate of an H100’s server cost to $190k for hyperscalers $23.7k / GPU, so GPUs themselves would be cheaper still.

- In a small dataset we collected of public price listings, H100 servers generally cost ~35k per GPU, without a clear trend over time.

Overall, there is a relative consensus of reports of H100 prices in the low to mid 20k range by 2024 and 2025. We have more uncertainty about the average price in 2023, when there was reportedly a widespread shortage of H100s.

H200 vs H100

In 2024, Nvidia started selling the H200, a mid-cycle update to the H100. The main difference is improved memory: 141 GB vs 80 GB for the H100. High-bandwidth memory generally costs $10-20 per GB, so the H200 is ~$1k more expensive to produce than the H100, implying a price increase of ~$4k if Nvidia applied its overall GPU gross margin of ~75% to this additional cost.

Nvidia never broke H200 vs H100 sales, but at least one analyst predicted that the majority of Hopper sales would be H200 from H2 2024. So it is possible that the introduction of the H200 meaningfully increased the average price of Hoppers (relative to if all sales were H100).19

Reconciling with Jensen Huang’s volume disclosures

In late 2025, Jensen Huang claimed that Nvidia had sold a total of 4 million Hopper GPUs for $100 billion in total, excluding sales to China (that is, 4M H100s and H200s, not including H20s or H800s). This suggests an average sales price of ~$25k across the generation, ignoring the possibility of rounding.

A deeper look into Hopper revenue complicates this picture: if we estimate total Hopper revenue by multiplying Compute revenue by our estimates of Hopper share of Nvidia’s GPU sales, this yields a total of ~$126B, not including networking. This could be consistent with “$100B” due to rounding. But it suggests average revenue of closer to ~$30k (which would imply ~4.2M total sales) rather than $25k (meaning 5M total sales, which is less likely to be rounded down to 4M).

There are a few reasons our estimated Hopper revenue could differ from the reported $100 billion besides rounding:

- As noted above, Nvidia makes some revenue from selling H100 servers or server equipment (though this arguably should be included in Jensen’s Hopper revenue total).

- L40 sales: the L40 is a lower-grade data center GPU launched around the same time as the H100; we round down L40’s share to zero for simplicity, which means those sales are implicitly rolled into the H100 total. It seems hard to believe that Nvidia sold close to $20 billion in L40 GPUs, though one analyst did forecast that L40 sales would reach $2 to 3 billion in 2023.

- Our allocations to A100 and Blackwell may be too low, though their earnings commentary on these splits (compiled here) is fairly specific.

- Compute revenue from software or other peripheries could be higher than we think (we model it as 1-4%).

Our overall credence intervals for average Hopper (H100/H200) prices are listed below. Because the H100 and H200 were on sale for over three years, we break down our estimates by year.

| Year | Low price | High price | Geometric mean | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 27k | 35k | ~29.6k | Low volume in 2022 in any case |

| 2023 | 27k | 35k | ~30.7k | |

| 2024 | 25k | 32k | ~28.2k | H100s were reportedly 20k-25k by late 2024. This may be pushed up by the H200. Adjusted upwards due to possible server revenue and CEO’s volume disclosure. |

| 2025 | 22k | 30k | ~25.6k | Entire H100 server costs reportedly in low 20k range by 2025, but H200s are more expensive. Adjusted upwards due to possible server revenue and CEO’s volume disclosure. |

H800

Reuters reported that 8-GPU H800 servers were sold for 2 million yuan, or ~$280k. This is similar to SemiAnalysis’ 2023 report of $270k for an HGX H100 server, suggesting a similar price for the GPU. One article notes a range of “street” prices for H800s from $35k up to $69k, though the higher end is almost certainly not representative.

Overall, we use a range of 25k to 35k, identical to what we use for H100s.

H20

Based on several sources, unit prices were typically in the low-10k range. Reuters reports they sold for $12k to 15k “per card” in February 2024, while TechPowerUp reported $12k in July 2024. Reuters also reported in February 2025 that “Analysts estimate Nvidia shipped approximately 1 million H20 units in 2024, generating over $12 billion in revenue for the company.”

Given these reports, we use the following price assumptions:

| Year | Low price | High price | Geometric mean | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 10k | 15k | ~12.2k | Most reports in 2024 converge on 12k to 15k |

| 2025 | 10k | 13k | ~11.4k |

Blackwell (B200 and B300)

Nvidia’s next-gen Blackwell chips were released in late 2024 and come in three variants: B100, B200, and B300 (aka Blackwell Ultra).

B200s and B300s are the flagship GPUs of Blackwell, with B300 being a mid-cycle upgrade. They are mostly deployed in the form of GB200 and GB300 systems, which contain one Nvidia Grace CPU per two Blackwell GPUs, with the most common configuration being NVL72 server racks containing 72 Blackwell GPUs.20 GB200/GB300 systems have a 10% higher FLOP/s rating per GPU than standalone B200/B300s.

Overall, NVL72 appears to be the overwhelmingly popular form factor for Blackwell.21 Given the predominance of NVL72, B100s are likely a low-volume product and we group them together with B200s.

How much do B200s and B300s cost? Let’s start with B200 and discuss how the B300 differs.

For estimating the price of (G)B200s, there are two possible approaches: (1) find the price of standalone B200 GPUs, or (2) estimate the price-per-GPU of NVL72 systems, and adjust downwards for non-GPU costs like networking.

For standalone B200s:

- Jensen Huang also said in March 2024 that standalone B200s would be priced between 30k and 40k each.22

- We estimated that B200s cost ~$6400 [5.7k to 7.3k] to produce based on a bill of materials breakdown. At a gross margin of 75-80%, this implies a price of $25k to $32k, or $22.8k to $36.5k if multiplying the ends of the production cost confidence interval.23 This is arguably a less credible method than using financial reporting, especially when we don’t know the margin for B200 GPUs specifically.

Meanwhile, the price of GB200 NVL72s is fairly well documented:

- SemiAnalysis estimates that GB200 NVL72 servers cost between 3.2M and 3.5M, varying for hyperscalers and neoclouds, or 44k to 49k per GPU, implying an industry average somewhere in between.

- Another source (HSBC) gives a somewhat lower estimate: $2.6M for NVL72 GB200s (36k per GPU). Other analyst estimates (from mid-2024, before GB200s were widely available) were at $3 million per system, or ~$41.7k per GPU.

- HSBC analysts also estimated the price of GB200 superchips (two GPUs) at $60 to 70k, or $30-35k per GPU.

However, the effective price of GB200s (Nvidia Compute revenue per GPU shipped) will be lower than this:

- NVL72s contain a significant amount of networking equipment, so part of the price accrues to Nvidia’s Networking segment. Nvidia has said that its Networking revenue is increasing rapidly, “driven by the growth of NVLink compute fabric for GB200 and GB300 systems”, among other factors. Networking was 18% of Nvidia’s total data center revenue that quarter, a rough upper bound on what portion of the cost of an NVL72 accrues to Nvidia Networking (Nvidia also sells cluster-level networking equipment outside the server racks themselves).

- As with H100 servers, some share of GB200 servers is sold by server OEMs or assembled by hyperscalers, in which case the cost of components that aren’t proprietary to Nvidia don’t flow to Nvidia.

Overall, these NVL72 figures point to a range of 35k to 40k per GPU. We use a price range of 33k to 42k for GB200s (a somewhat unprincipled widening of 35K-40K, which is a narrow range but would be a reasonable choice for a middle-50% interval).

GB300 vs GB200

How might GB300s differ in price from the GB200?

- HSBC estimates that GB300 NVL72s sell for $3M, or ~15% higher than their $2.6M figure for GB200 NVL72 (this ratio shouldn’t be taken very literally; while the institution is the same, the methods and timeframe could vary and there could be rounding).

- Apple (not a hyperscale buyer of AI compute) reportedly paid $3.7M to 4M per GB300 rack, or 51-55k per GPU. This is 10-20% higher than SemiAnalysis’ reported “neocloud” pricing for GB200 NVL72.

- The B300 differs from the B200 in logic die and other components, but likely the greatest cost driver is the ~100GB increase in memory per GPU . If the HBM costs $15/GB and priced at a 75% margin (see H200 discussion above), this would increase the GPU’s price by ~6k vs the B200. This suggests a ~20% price increase.

A naive model of applying a 10-20% premium on our GB200 interval, with no correlation between GB300 premium and GB200 price, suggests a GB300 price range of 38k to 49k. The higher end is consistent with higher-end reports of GB300 NVL72 systems bought by Apple.

Reconciling with direct Nvidia statements

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang disclosed that through October 2025, Nvidia had shipped a total of 4M Hoppers (H100s and H200s) and three million Blackwell GPUs through October, excluding the Chinese market in both cases. (excluding China sales): 4M Hopper GPUs, and 3M Blackwell GPUs (technically, he says 6M Blackwell GPUs, but he’s referring to the two individual dies within each GPU package)24

How does this compare with our estimates? Our model puts overall Nvidia GPU shipments through October 2025:

- 4.3 million H100s, excluding A800s, H800s

- 2.54 million Blackwell GPUs (1.6M B200s and 940k B300s) through October 2025

These aren’t perfectly consistent, especially the Blackwell total which is ~15% lower than 3 million. Since the 3M Blackwell count is actually derived from 6M Blackwell dies divided by two, this isn’t explained by rounding, since ~2.5M Blackwell GPUs would be 5M dies.25

Some other potential explanations for the Blackwell difference:

- Since our Hopper count is slightly high and Blackwell count is low, we might be misallocating the revenue between generations, though their earnings commentary (compiled here) on the Hopper/Blackwell split in 2025 is fairly specific

- We use the prices and specs of GB200 and GB300s. But B200 and B300 chips are slightly cheaper, and the somewhat less powerful B100 is cheaper still. So if these variants have a significant share of Blackwell, this would increase GPU counts (while also reducing compute power per GPU). Our GB200/GB300 split could also be off: the GB300 is more expensive.

- Our Blackwell price estimates could be slightly too high in general

Given that the conclusions are not far off, we won’t attempt to fully resolve this difference. We intend to continue modeling Nvidia chip shipments after October 2025, and not just Hopper and Blackwell, so our focus is on building the best comprehensive model of Nvidia sales.

Notes

-

1.4 million if the wafers they forecast would be used for Trainium3 were reallocated to Trainium2. Trainium3 was announced near the end of 2025. ↩

-

This was estimated by digitizing the chart image. ↩

-

If H2 shipments are 25-56% higher than H1 and total for 2025 is 2M, then H1 = 2M / (1 + growth factor) = 2M / 2.25 to 2M / 2.56 = 780k to 890k. ↩

-

“Amazon and Annapurna are heavily cost focused and drive their suppliers hard. Compared to Broadcom’s ASIC deals, the Trainium projects have much less profit pool available to the chip design partners Alchip and Marvell.” ↩

-

But well behind Google/Broadcom overall. ↩

-

Not including AMD’s gaming GPUs which can be used for AI/ML but are not designed for it. ↩

-

Recently, Google/Broadcom have also decided to start selling TPUs directly, e.g. to Anthropic and to other cloud companies. These deliveries will likely begin in 2026 and the TPU volumes we estimate are presumably owned entirely by Google. ↩

-

This was disclosed because Broadcom’s CEO, Hock Tan, is on Meta’s board. Not all of this revenue from Meta necessarily went to XPUs, in which case Google’s share of XPUs would be even higher. ↩

-

The assumptions that TPU spend with Broadcom scales proportionally with overall CapEx may not hold exactly if spending shifts toward data centers, networking, or other areas. ↩

-

For example, they forecast in Q2 that overall gross margins would decline “primarily due to a higher mix of XPUs in AI revenue” implying XPUs have a lower margin than their overall AI business. Hock Tan also didn’t push back against a caller who said “custom [chips] is probably dilutive within semis”. ↩

-

The values in the Squiggle modeling may very slightly differ from the values in the table due to small stochastic variation from independent Monte Carlo draws, as well as minor implementation differences in how distributions are represented and sampled, despite identical parameter ranges and distributional assumptions. The values reported above are from the Python notebook that we derive the final estimates from. ↩

-

If a TPU version did not have a Preview period and instead moved directly to General Availability (GA), we list the GA date. ↩

-

See estimates of chip lifespan in “Analysis” here. It is possible that some 2022-era chips have already been retired but we don’t explicitly model retirements/failures for simplicity. ↩

-

For 2022, an explicit Networking breakout was not available, so we estimate/interpolate this as 75% Compute (networking share has generally gone down since 2020). ↩

-

As a very minor point, Nvidia actually report two sets of breakdowns. Nvidia has two “reportable segments”: “Compute & Networking” and “Graphics”. Nvidia also reports a separate breakdown over several “market platforms”, including Data Center. Within Data Center (which is what we use), revenue further is broken into “Compute” and “Networking”. For whatever reason, Data Center revenue (“Compute” plus “Networking”) is ~1% smaller than the “Compute & Networking” reportable segment. ↩

-

Nvidia’s cloud reportedly runs mostly on rented capacity from Oracle and neoclouds. Nvidia also uses external cloud compute for at least some of the compute it uses for internal research and model training. This suggests that Nvidia owns very little of its own hardware (besides undelivered inventory, which we don’t include in our counts). ↩

-

Networking equipment within a server would count as Networking revenue. ↩

-

“we think if it was any higher than that, OEMs and ODMs would be screaming”, referring to third parties that sell Nvidia servers or assemble them as a service. ↩

-

The fact that Nvidia received an export license to sell H200s, but not H100s, to China in late 2025 is perhaps a sign that the H100 was out of production or irrelevant by that time. ↩

-

Alternatively, they can be deployed in 8-GPU B200 servers or standalone. ↩

-

Nvidia said that by April 2025, hyperscalers were deploying almost 1000 NVL72 racks per week. At $2 to 3 million in revenue each, this would be 13 * 1000 * 2-3 million = $26B to 39B in revenue, versus $41 billion in total data center revenue the following quarter. ↩

-

Full quote (while holding up a physical B200 die): “This will cost, you know, 30, 40 thousand dollars” ↩

-

Company wide gross margin is about 75%, and could be higher for AI GPUs specifically. ↩

-

The graph says 6M Blackwell GPUs, the small text on the slide “Blackwell and Rubin are 2 GPUs per chip” indicates that this is a case of Jensen math: he is counting the two GPU dies in each package as a separate GPU. So 6M actually means 3M Blackwell GPUs as traditionally understood (as in, a standalone B200 contains two GPUs under this accounting, and an NVL72 system contains 144). This is not a reference to the fact that GB200/GB300 superchips contain two (or four) GPUs each. ↩

-

And a CEO of a publicly traded company discussing sales figures would most likely round down, not up. ↩

Records

The AI Chip Production dataset describes estimated AI accelerator shipments in “timeline” batches broken down by time periods, chip designer, and chip type. The level of specificity in time period and chip type can vary by the available information and data.

We provide a comprehensive guide to the database’s fields below. This includes example field values as reference.

If you would like to ask any questions about the database, or request a field that should be added, feel free to contact us at data@epoch.ai.

Chip timelines

This is the primary data record, batching estimates of AI chip shipments by time period and chip type.

Organization

Organizations involved in chip design

Chip types

Metadata table with specifications for each chip model. This is a consolidated set of key fields; most of the data is synced with the Epoch ML Hardware dataset using the linked record.

Changelog

2026-01-29

TPU model updates

Updated TPU volume and compute estimates with revised assumptions on production mix and margins based on expert feedback.

In summary, we now model more rapid transitions to new TPU generations. Specific changes to our production mix estimates include:

- Removed TPU v3 from our 2022 estimates; limited v4i to late 2022

- Shifted v5e earlier; ended v4 after H1 2024

- 2024 modeled as v5e/v5p mix with increased v5p share

- Delayed v6e to Q3 2024; becomes dominant by Q1 2025

- v5e phased out by end of 2024; Q3 2025 transitions from v6e to v7

Revisions to Broadcom’s gross profit margins:

- FY23: 55–70% (down from 65–75%)

- Post-FY23: 50–65% (down from 50–70%)

Implications:

- These changes have a significant impact on the implied compute capacity of TPUs. Compared to the previous version, the updated model estimates 36% more compute capacity from TPUs, due to faster ramps of more advanced TPUs such as v6e.

- The effect on unit volumes and total cost is much smaller. The updated model estimates 5.28% more TPU units and 2.73% higher total cost than the prior model.

Code refactoring

Ported our TPU and AMD models to Python Jupyter notebooks, which we previously used for Nvidia, and refactored all three models to use similar formats and helper functions. These can be found in Epoch AI’s ai-chip-counts repository.

The new models are functionally the same as before, with some specific modeling updates:

- We now model AMD and TPU price uncertainty as log-normally distributed, instead of uniform or normally distributed respectively (Nvidia was already log-normal). This is a more appropriate modeling choice given exponential changes in chip price-performance over time, but only has a minor impact on our median estimates or confidence intervals.

- We discovered and resolved a bug in the Nvidia code where it was using higher prices for 2024-2025 than intended (leading to a reduced unit count estimate). However, because correcting this bug resulted in an estimate of H100 and H200 shipments that is apparently higher than the amount disclosed by Nvidia, we slightly revised our price assumptions upwards, with ultimately almost no net change in cumulative H100/H200 sales.

Data refactoring

Reorganized our “Timelines by chip” tables into a single table, with substantially similar columns, instead of multiple tables broken down by designer. In addition, the rows in the table are now all broken down by calendar quarter, where previously they were often broken down by fiscal quarters that do not line up with calendar quarters (e.g. for Google TPU and Nvidia) or other non-quarter periods such as years or half-years. This does not affect our graph views, which previously already interpolated the table results into calendar quarters.

Our models still output intermediate results broken down by fiscal quarter when they are distinct from calendar quarters, which you can view in the respective code notebooks (see full methodology).

Downloads

Download the AI Chip Sales dataset as individual CSV files for specific data types, or as a complete package containing all datasets.

Timelines by chip CSV

CSV, Updated February 12, 2026

Organizations CSV

CSV, Updated February 12, 2026

Chip types CSV

CSV, Updated February 12, 2026

AI chip sales ZIP

ZIP, Updated February 12, 2026

Acknowledgements

This data was collected by Epoch AI’s employees and collaborators, including John Croxton, Josh You, Venkat Somala, and Yafah Edelman.

This documentation was written by Josh You and Venkat Somala.